Our updated UX Maturity Model incorporates new norms and adapts to the evolution of our industry. It outlines how UX maturity can be shaped and measured. There are six stages of UX maturity (Absent, Limited, Emergent, Structured, Integrated, and User-Driven). However, companies at the same stage might look different due to organization specifics such as size priorities, or politics.

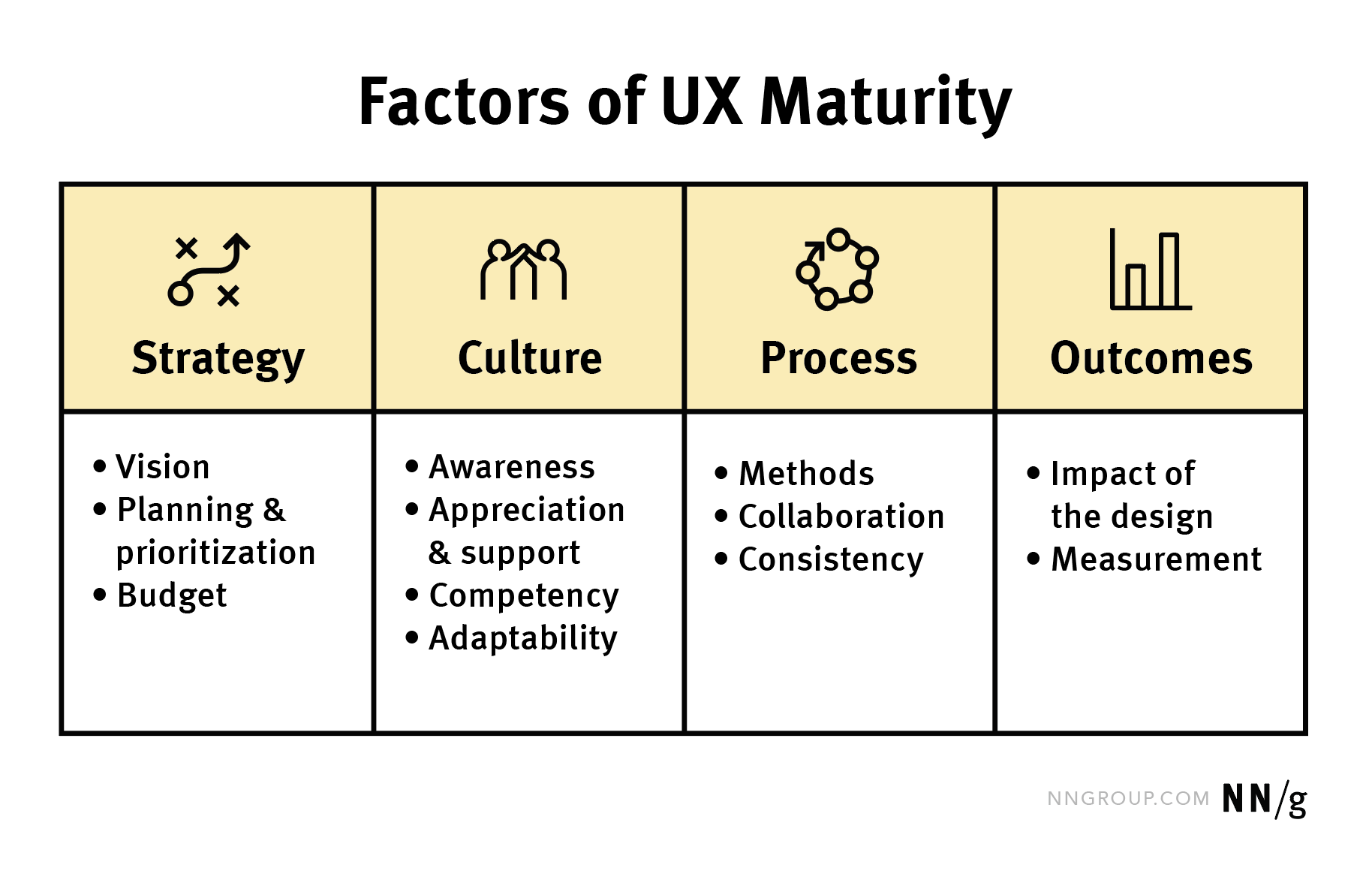

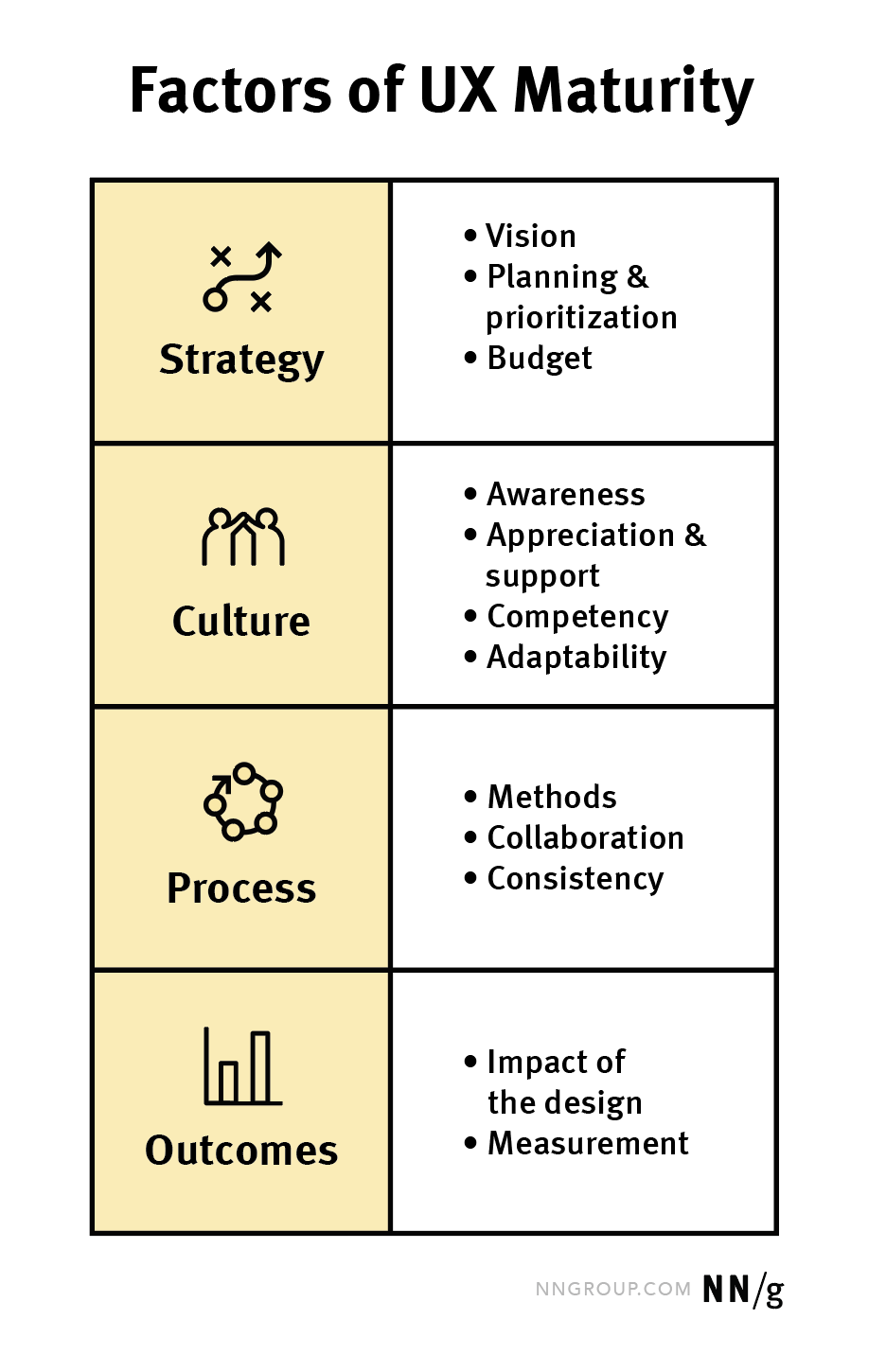

We identified 4 high-level factors that contribute to the organization’s UX maturity:

- Strategy: UX leadership, planning, and resource prioritization

- Culture: Knowledge about and attitudes towards UX, as well as cultivating UX careers and practitioners’ growth

- Process: Systematic, efficient use of UX research and design methods

- Outcomes: Intentional definition of goals and measurement of the results produced by UX work

Each of these 4 high-level factors influence the organization’s UX-maturity level. These factors provide a framework to assess the organization’s commitment to UX and its ability to deliver user-centered products and services across all areas of the organization.

None of these factors stand alone; rather, they reinforce and enable each other. Further, each factor can be broken down into subfactors — dimensions that contribute to the quality of a given factor. Organizations must progress in all these dimensions in order to reach high levels of UX maturity and realize the full value of user-centered design. They can, however, be stronger in some factors so make up for deficiencies in others.

This article outlines the four high-level factors, as well as their corresponding subfactors. We hope they will help you identify and evolve elements that are integral to the growth of your organization’s UX maturity.

A. Strategy

Strategy includes all high-level decisions and planning that contribute to the success of UX work before it begins. Strategy can be broken down into 3 subfactors:

A.1 Vision

One or more declared user-centered organizational objectives that guide internal, crossdisciplinary decision making are key to UX maturity. This subfactor considers whether things like yearly objectives, crossdepartmental alignment, and leadership are UX-oriented.

In low-maturity organizations (stages 1–3), a vision that includes UX is rare (or if it even exists, isn’t well-communicated).

In high-maturity organizations (stages 4–6), a vision includes strong, thorough user-centered ideas, is deliberately and strategically communicated, and guides the entire organization (UXers and everybody else).

A.2 Planning and Prioritization

In order for UX work to prosper, UX efforts should be accounted for and prioritized, throughout the product lifecycle. This subfactor accounts for whether aspects like development schedules and processes, operationalized systems, and standardized decision making take UX into account.

Low-maturity organizations’ schedules and development processes seldom mention UX, and if they do, UX is used to validate or improve existing designs, rather than drive new ones.

In contrast, high-maturity organizations implement a shared method for project prioritization, regularly track user-experience quality, and allow good research to drive projects.

A.3 Budget

Organizations must allocate adequate resources — people and time — to UX and invest in future UX initiatives.

Low-maturity organizations are marked by a lack of full- or part-time UX people and use only budget scraps to fund UX projects. The few UXers they have are spread too thinly across multiple product teams.

High-maturity teams have adequate UX budgets that are allocated mindfully and systematically (rather than haphazardly and inconsistently). UX work is prioritized and resources are used both for refining existing designs and creating new product capabilities that respond to users’ needs.

B. Culture

Culture encompasses ideas that contribute to the organization’s understanding of the purpose and value of UX. There are 4 subfactors that enable a positive UX culture:

B.1 Awareness

This subfactor looks at how widespread knowledge of UX and its benefits is across the organization (beyond the UX staff). It includes an organizational-wide interest in learning UX.

In low-maturity organizations, the UX mindset usually doesn’t exist or if it does, there is leader-to-leader discrepancy and many think UX is just polish at the end of product development.

In high-maturity organizations, there is a broad understanding that UX impacts products and services from the inception phase and applies beyond interfaces. In fact, a UX skillset often plays an equal role (and might be a prerequisite) alongside other skillsets.

B.2 Appreciation and Support

For UX to succeed and thrive, people outside the UX team must support and be involved with UX work. Widespread respect for UX, proactive assistance, positive reinforcement, and championing by others are important.

Low-maturity organizations have leaders who are indifferent to UX and struggle with a lack of respect for the future-oriented aspects of UX (for example, discovery research) and inconsistent buy-in for UX across leaders and colleagues.

In contrast, high-maturity organizations have strong assistance for good UX across teams, UX is well-respected among peers, and there is UX expertise and support at the highest level (C-suite).

B.3 Competency

This subfactor captures how well-defined skills related to UX practice and expertise are and how much they are cultivated throughout the organization. This subfactor looks at whether the organization has dedicated UX-roles, a breadth of skills in UX teams, and pertinent hiring practices.

In low-maturity organizations, there are usually no dedicated UX roles or titles. If there are any, the people in those roles cannot effectively sustain their work because they are part of teams that are not UX-minded. These organizations also often miss specific skillsets needed to establish UX basics like benchmarking or qualitative research.

As organizations evolve to be high-maturity, human-resources elements (like job profiles and career paths) not only exist but cover a wide range of UX skills. Hires are made to specific UX-roles depending on team needs and UXers are encouraged to grow their skillset through mentorship and additional training.

B.4 Adaptability

For UX to evolve, a spirit of persistence, flexibility, and sustainability around UX work is key. This subfactor addresses whether the organization is 1) willing to advance best practices and adjust approaches to improve, and 2) logistically able to adapt to changing needs.

Low-maturity organizations are often rigid when it comes to adjusting processes in order to incorporate a UX mindset or respond to new UX challenges. They may adopt some UX-oriented workflows but apply them undiscerningly and be unwilling to change them when facing new UX challenges or problems. They may also not have the capabilities or the knowledge to change their processes due to understaffing or lack of specialized UX expertise. Their UX practice may depend on one or two people; if these people leave the company, the practice dies.

In mid-to-high maturity organizations, there is both a willingness and logistical ability to adjust processes based on the context and needs of the team. If personnel changes, the product team can continue without having to start from scratch.

Awareness, appreciation, competency, and adaptability together create a positive, proactive culture where UX work can be understood, valued, and improved.

C. Process

The process factor encompasses all UX work that occurs (research, design, content creation, etc.) within an organization. It breaks down into three subfactors:

C.1 Methods

This subfactor addresses whether there is established use of user-centric techniques throughout the entire product lifecycle: design practices, qualitative- and quantitative-research approaches, and iteration.

Low-maturity organizations suffer from a lack of methods, often used incorrectly. Also, in such organizations, UX methods are frequently used in response to a specific business need, rather than being embedded into everyday work. Research is limited to ‘easy’ methods instead of appropriate methods; findings from research rarely lead to design changes.

In comparison, in high-maturity organizations, a variety of design and research methods are used across the entire development lifecycle. Iterative design is common and discovery research is a prerequisite for most projects. Extremely high-maturity organizations may even create new methods or refine existing ones and set new industry standards.

C.2 Collaboration

To be successful, UX teams must work with other departments. This increases common ground and the creation of diverse ideas.

Low-maturity organizations don’t realize that crossfunctional teams should be involved in UX; rather, they think that only those with “UX” in their title should be responsible for UX. In these cases, inconsistent success metrics make collaboration difficult and cause it to occur only for part of the development process.

In high-maturity organizations, collaboration is embedded in the company’s DNA. UX professionals routinely cooperate with other roles and most teams perform regular standups and retrospectives.

C.3 Consistency

This subfactor addresses the existence and utilization of shared systems, frameworks, and tools that allow consistent inclusion of a UX mindset in various processes and free practitioners to think strategically.

The only common thread related to UX in low-maturity organizations is that any UX activities are one-off and, thus, not reproducible or comparable.

High-maturity organizations invest in establishing consistent tools, training, information, and resources around UX design and research. Frameworks exist across the organization and are shared, maintained, and improved. This approach ultimately ensures that the design process can be similarly applied across teams and projects in a sustainable manner.

Process is an important factor in the success of all UX work — it is how things get done, the methods used to do them, and who contributes to them.

D. Outcomes

This factor highlights the result of UX research and design. These outcomes of UX work should be intentionally defined by establishing clear UX goals and objectives that are explicitly documented, shared, and measured by the product team and its stakeholders. This is a key factor in UX maturity because it allows organizations to understand the effectiveness of UX work overtime. Outcomes comprise two subfactors:

D.1 Impact of the Design

Success, at a company level, should be rooted in meeting not just business goals, but also the needs of real users. This subfactor looks at the quality and effectiveness of the implemented design from a user-centered perspective.

In low-maturity organization, the success of the design is based on a checklist of feature capabilities, rather than usability and user needs.

In high-maturity organizations, the success of the design is based on how much it answers the project goals and meets real user needs.

D.2 Measurement

This subfactor addresses the mechanisms in place to track the impact stated above. An organization should have clear user-centered metrics and a process in place for tracking them.

Low-maturity organizations usually chase metrics that have nothing to do with the user. Even if they do have a few token user-centered metrics, there is no system in place to track them.

High-maturity organizations have user-centered goals that drive metric creation. These metrics are effective at measuring UX, encompass aspects of the entire user journey, are monitored and updated, and are used at the highest leadership level.

Applying UX Maturity Factors

Determining Maturity Using the Factors

Simplistically, you could think of each individual subfactor contributing equally to each factor, and each factor in turn contributing equally to the overall UX maturity of an organization. Thus, you could assign scores (say, on a scale from 1 to 5) for each subfactor; then average the subfactor scores to get the score for a factor, and finally, average the factor scores to get the overall maturity.

You can also self-assess the UX maturity of your organization by taking our free UX-maturity quiz.

However, in practice, things are a little more nuanced. In some organizations, certain factors may carry more weight than others. For example, in extremely traditional, hierarchical companies, Strategy may impact an organization more than process (due to leadership being more likely to play a role in dictating process standards that are respected and followed). Inversely, in startups, where there is little strategic planning and a quickly evolving vision, the Process factor (and its subfactors) may play a larger role in the overall maturity.

Given this contextual complexity, a complete evaluation of an organization’s UX maturity should be based on diverse, company-tailored assessment methods, including conducting research, observing work practices, interviewing and surveying employees at different levels in the organization, analysis of processes, people, tools, and deliverables.

Variation Within a Stage

No two organizations are the same. They have different strengths and weaknesses, sizes, missions, and obstacles. Thus, organizations can look quite different even if they fall within the same UX-maturity stage.

For example, imagine two companies, both at stage 3 (Emergent). Company A is a startup with leadership highly fluent in UX; thus, its strategy is deeply rooted in research and user-centered needs. However, due to the limited headcount, it cannot practice UX design and research methods soundly and consistently across all its initiatives. Thus, while company A’s Strategy factor sits at a higher maturity, the organization stays at stage 3 due to a lower maturity in Culture and Process.

In contrast, imagine that organization B is a department within a large enterprise. (While we feel UX maturity should be measured at an organization-wide level, we also see benefits of analyzing individual departments’ maturity separately in very large organizations with lots of variation across departments.) Politics plays a significant role in its strategy, thus leading to metrics that are not user-centered and competing priorities. However, UX competency is high: the department has the right skillset, produces sound research, and somewhat consistently applies its UX process. As a result, organization B is also at stage 3 — for different reasons than company A. While B’s Process and Outcomes are sound, its Strategy and Culture hold it back from evolving to a higher maturity.

In this way, the maturity factors can be used to identify the UX-maturity profile for a given company. Use them to assess your organization’s maturity, determine weaknesses, develop a plan for improvement.

It is usually best to grow all the maturity factors and subfactors in parallel rather than focusing on optimizing a few subfactors, for two reasons:

- The investment needed to reach the highest levels is usually more than that needed for lower levels. ROI is, thus, optimized by improving your low-scoring subfactors.

- Various subfactors work to enhance each other and the resulted synergy reflects positively over the UX maturity of the organization. Some of this synergy is lost if one or two subfactors run far ahead of the rest.

We offer a variety of consulting projects to help you assess and improve your UX Maturity. Please contact us if you are interested: consulting@nngroup.com.

Share this article: