When brands and organizations seek growth by expanding into a global market, they may find that their digital products are not as popular as in the domestic market.

Beyond marketing factors, one frequent cause is that their websites and apps are initially developed for and tested within a local demographical profile. What has been working well for that domestic group may not make any sense to people from a different cultural background. This is why designers must modify the products for a global audience and test with that target audience to validate the modifications.

Two Types of Adaptation

For digital products with crosscultural audiences speaking different languages, there are two adaptation approaches:

- Translation means that the interface language changes depending on the target audience. The look and feel of the product stays the same; the only difference is the language.

- Localization refers to making the design of the digital product culturally relevant to the target audience. This type of change is often more dramatic: visual presentation and content strategy can be totally different.

These types of adaptation are two ends of a spectrum of possible approaches to cultural differences: a product can fall anywhere on this spectrum.

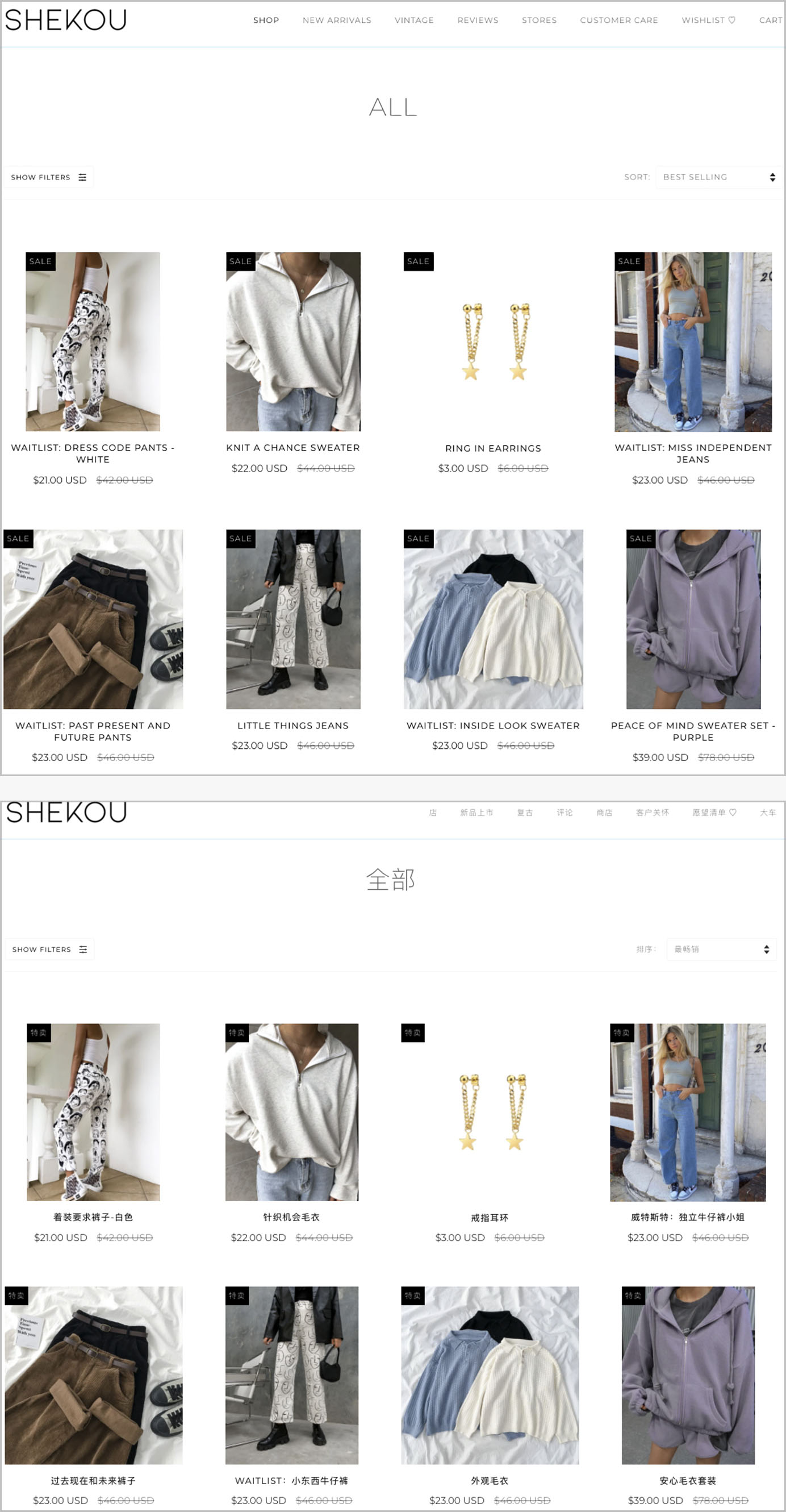

For example, the New Zealand fashion brand Shekou Woman offered various language options on its website. For each language, the visual design and content stayed the same: only the language changed. Shekou is an example of a translation-only approach to dealing with diverse audiences.

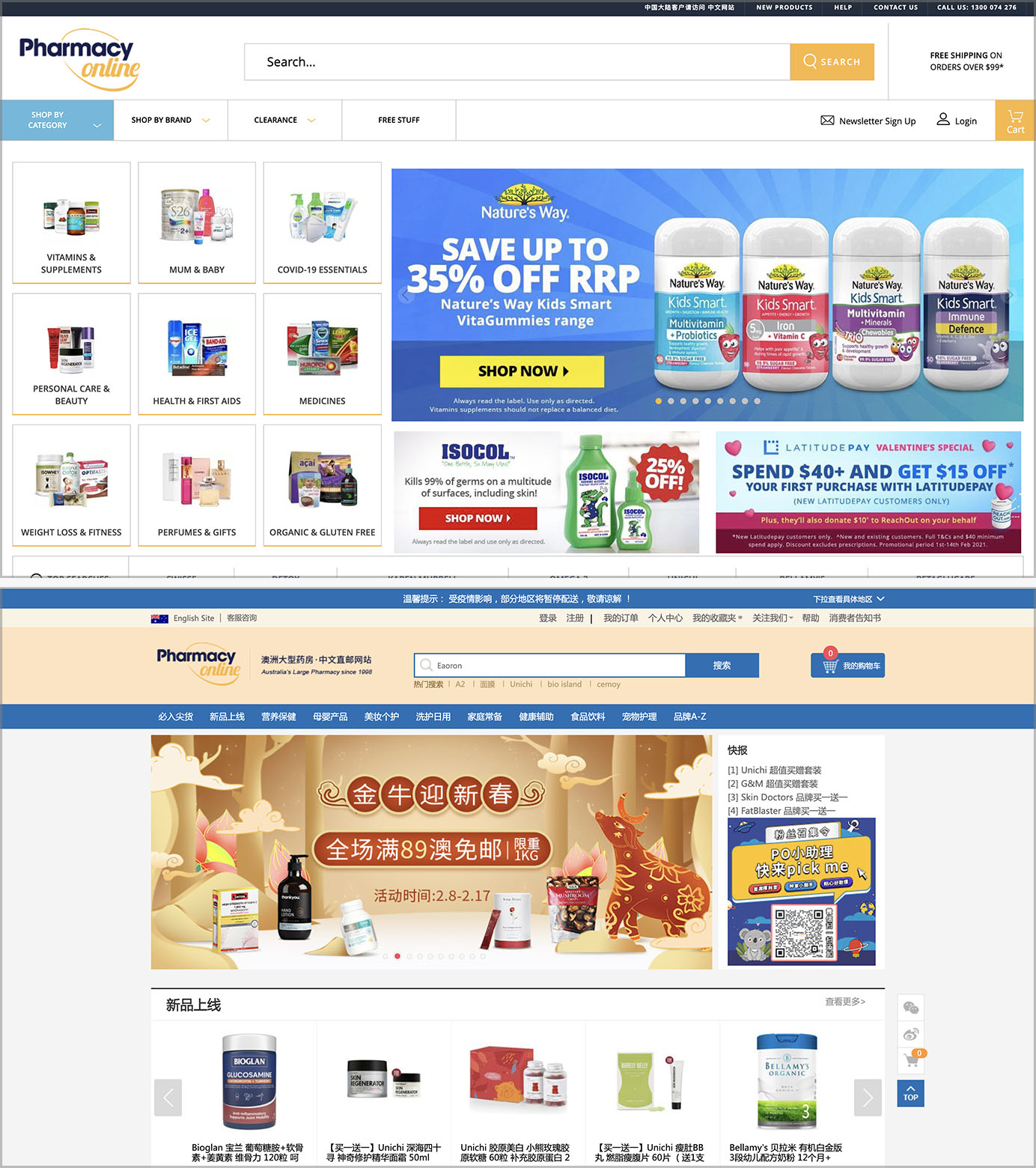

In contrast, Pharmacy Online, an Australian pharmacy website, showed different designs to its Chinese and English-speaking visitors. The navigation, information architecture, visual design, and promoted products were all different.

Many other digital products fall in the middle ground between localization and translation, tailoring their content and visual presentation to a certain degree.

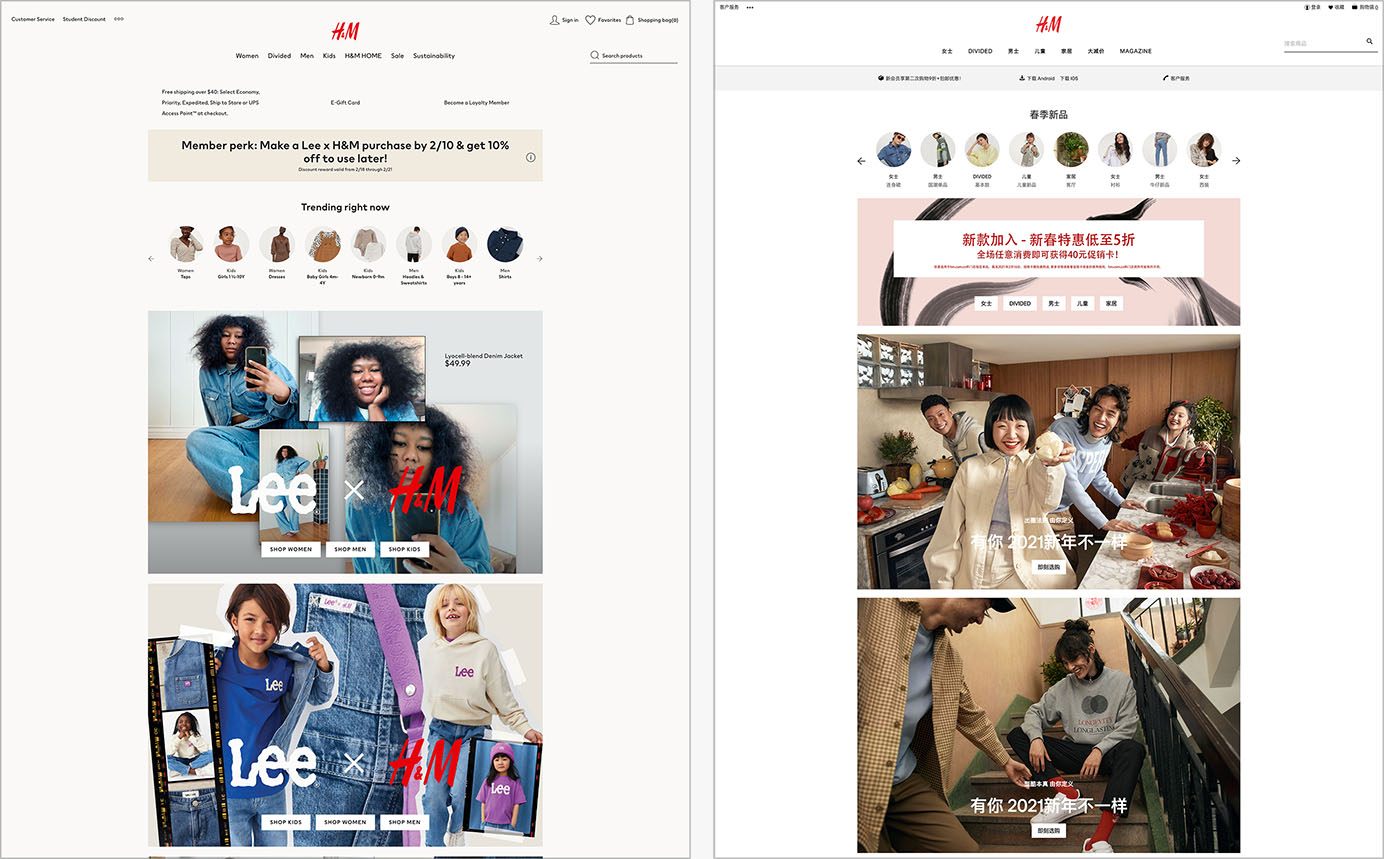

For instance, H&M’s Chinese and American versions had a similar look and feel: they used the same information architecture and visual design. However, the Chinese version emphasized Lunar New Year Sales on all its banner pictures and used Asian models; the US version promoted a special collection with local models.

Ideally, you should have a culturally specific version for every country or region you provide services for; this approach is pretty typical for big global companies. For each version, the localization level depends on how people with the respective cultural background differ from domestic users.

Still, sometimes it’s not feasible, worthwhile, or even necessary to have local designs for every culture, especially for smaller businesses. In this case, products or services rely mostly on translation and simply offer multiple language options.

There isn’t a one-for-all solution when you modify your design for global audiences. Next, we discuss some key factors you should consider to decide where your product should sit on this spectrum.

Factors Impacting Crosscultural Designs

For a specific digital product targeting international audiences, you must decide how much to tailor the products to users from different cultural backgrounds.

Here are some factors to consider:

- The heterogeneity level of your target audiences

- General cultural differences between your target audience and domestic users

- How much cultural factors impact user behavior and the tasks supported by your product

- The brand image that you want to establish

- The potential value of your target market

The Heterogeneity Level of Your Target Audiences

First, identify culturally distinctive segments and their percentages, especially when your users are scattered all over the world.

If, like H&M, you already have culturally specific versions of your products, you’re getting a head start. However, if so far you’ve only relied on translations, it’s time to assess how culturally diverse your audience groups are. Even people using the same language may not be culturally homogenous. Users in France and in Quebec, Canada may both use the French version of your site, but they belong to different cultural groups and their behavior patterns may differ.

Within each of the languages spoken by your audience, define: (1) if there are any culturally distinct subgroups; (2) how big these subgroups are.

If none of these subgroups reach a sizeable portion of your general audience, then rely mostly on translation to deal with the users who speak that language. If one subgroup is a big part of your total audience, then consider creating a localized, culturally specific site for that group.

(For relatively smaller subgroups speaking the same language with your dominant users but from a different cultural background, offer a translated, culturally neutral ‘International’ version if possible. If that’s not feasible, stating the culturally specific content clearly, like promotions only for visitors from certain areas, can prevent minorities from misunderstanding.)

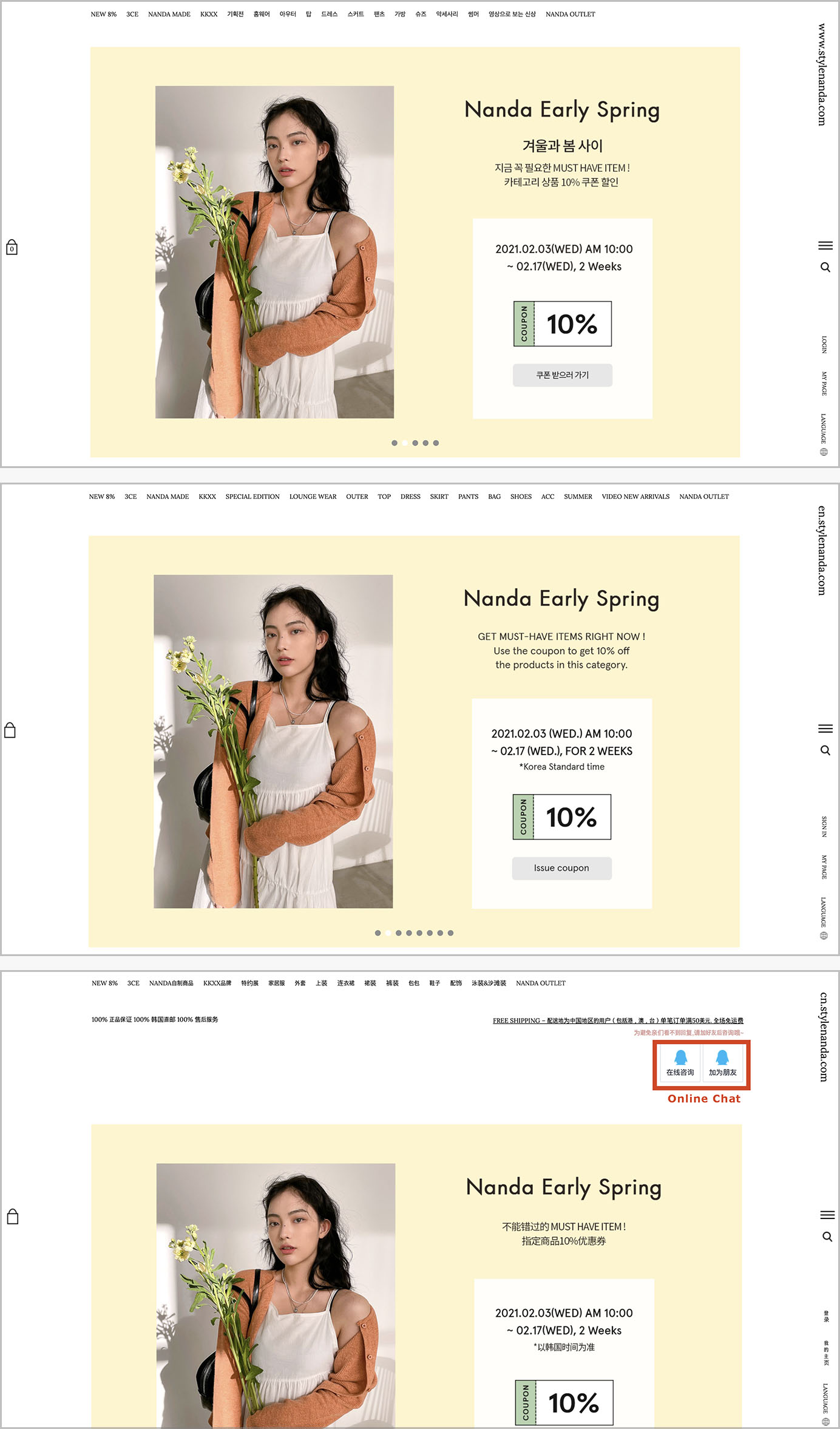

For example, Stylenanda, a South-Korean makeup and fashion brand offered international shipping, allowing shoppers all over the world to place orders on its website. However, it only provided 5 languages: Korean, English, Simplified Chinese, Traditional Chinese, and Japanese. Shoppers from Europe, Africa, and North America all had to use the English version. Stylenanda’s English website was not customized to any of these audiences because it would be too expensive and complicated to design multiple culturally specific versions for all English speakers worldwide, especially if most of the company’s revenues came from Asian purchasers.

In contrast, its Simplified Chinese version offered a special online-chat feature that wasn’t available on any other versions, using a popular Chinese instant messaging service, QQ. This feature is due to the relative homogeneity of shoppers using the Simplified Chinese version.

General Cultural Differences

After you identify a culturally homogeneous user group from your target audience and consider modifying your designs for it, you need to analyze how different they are from your domestic users and other cultures you target.

There are many possible approaches to this analysis. One is based on Hofstede’s cultural-dimensions theory, which defines 6 dimensions on which different national and cultural groups differentiate most. They are:

- Power distance: The extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.

- Individualism vs. collectivism: Whether people put more weight on the interests of the individual (individualists) or on the the interests of the group (collectivists).

- Masculinity vs. femininity: Whether strong, very different emotion stereotypes are associated with traditional genders (masculine societies) or emotions are allowed to overlap across genders (feminine societies).

- Uncertainty avoidance: The extent to which the members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations.

- Long-term vs. short-term orientation: Whether the society fosters virtues such as perseverance or thrift, oriented towards future rewards (long-term orientation) or virtues related to the past and the present.

- Indulgence vs. restraint: Attitude towards enjoying life and having fun, ranging from free gratification of human desires (indulgence) versus adhering to strict social norms (restraint).

You can use a comparison tool such as the one provided by Hofstede Insights to figure out how two countries differ. For instance, we can learn that Australia and the United States are relatively similar in terms of all 6 dimensions, while the Japan and US have different scores for individualism, uncertainty avoidance, and long-term orientation.

Another possible way of identifying cultural differences is through the theory of high-context vs. low-context cultures, proposed by anthropologist Edward T. Hall. Hall believes that people from high-context cultures prefer face-to-face communication and look for both less-direct verbal and subtler nonverbal cues during the communication. High-information density for various media formats is preferred by high-context cultures such as Chinese and Japanese. In contrast, people from low-context cultures (like the US and Scandinavian countries) rely on direct, explicit verbal cues during communication.

No matter which means you use to learn about the culture you’re designing for, noticeable cultural differences indicate the necessity of localizing the design. However, only looking at the general cultural differences is not enough; learning how cultural differences may impact your target audience's use of your offerings is vital.

Cultural Differences on Product Usage

Though cultural differences do exist, they don’t all influence how people interact with digital products.

Some factors are listed below for you to consider:

- Frequency. How frequently does your target audience use your product? The lower the frequency of use, the less localized the product has to be. However, if your product completely violates a local mental model and people use it rarely, there’s a high chance that they will make the same mistake again and again, in the few instances when they use it.

- Context. Where and how do your target users use your product? For example, do they solely use your site on a computer or do they need to check it on the go, on a mobile device as well? The more complex the context in which people use your products or services, the more localized the design should be.

- Interpersonal cooperation. Conduct a task analysis and learn how users achieve their primary goals. Does the task involve collaboration and communication between multiple users? If that’s the case, localized designs are more likely to be helpful since cultural differences can impact organization structures and hierarchies. For instance, an educational game designed to facilitate teaching may need more localized components than a time-killing single-person mobile game. The former involves more engagement of multiple roles.

- How local competitors differ from yours. Conduct competitor analysis or observe how your target audiences use products similar to yours. Analyze the differences between your product and its competitors and see whether they’re culturally specific, to uncover cultural mental models for common interaction patterns. For instance, during our ecommerce research, we observed that people in India and China preferred one-time passwords when asked to check out. Email registration wasn’t welcomed. In China, login through third-party platforms like AliPay and WeChat was also very popular. When a Chinese participant saw that a British-Portuguese ecommerce website, Farfetch, supported registration through WeChat, he was pretty amazed. “That’s wonderful and convenient. I have my mobile phone number and personal information on WeChat. If I use it to log in, there’s so much information I don’t need to fill in manually.”

In general, the more your products or services are involved in daily life, the more localized your design should be. Thus, deciding how localized your design should be or which components need localization requires understanding the full picture of how people from different cultural backgrounds use your product in their daily lives.

Branding

Deciding how localized your product should be also influenced by your branding. Designs can evoke emotional responses. Those emotional responses help people appraise your product and form an impression on your brand. Sometimes, making your product look a little bit exotic isn’t bad — it can contribute to establishing your brand’s image if people know that you’re foreign.

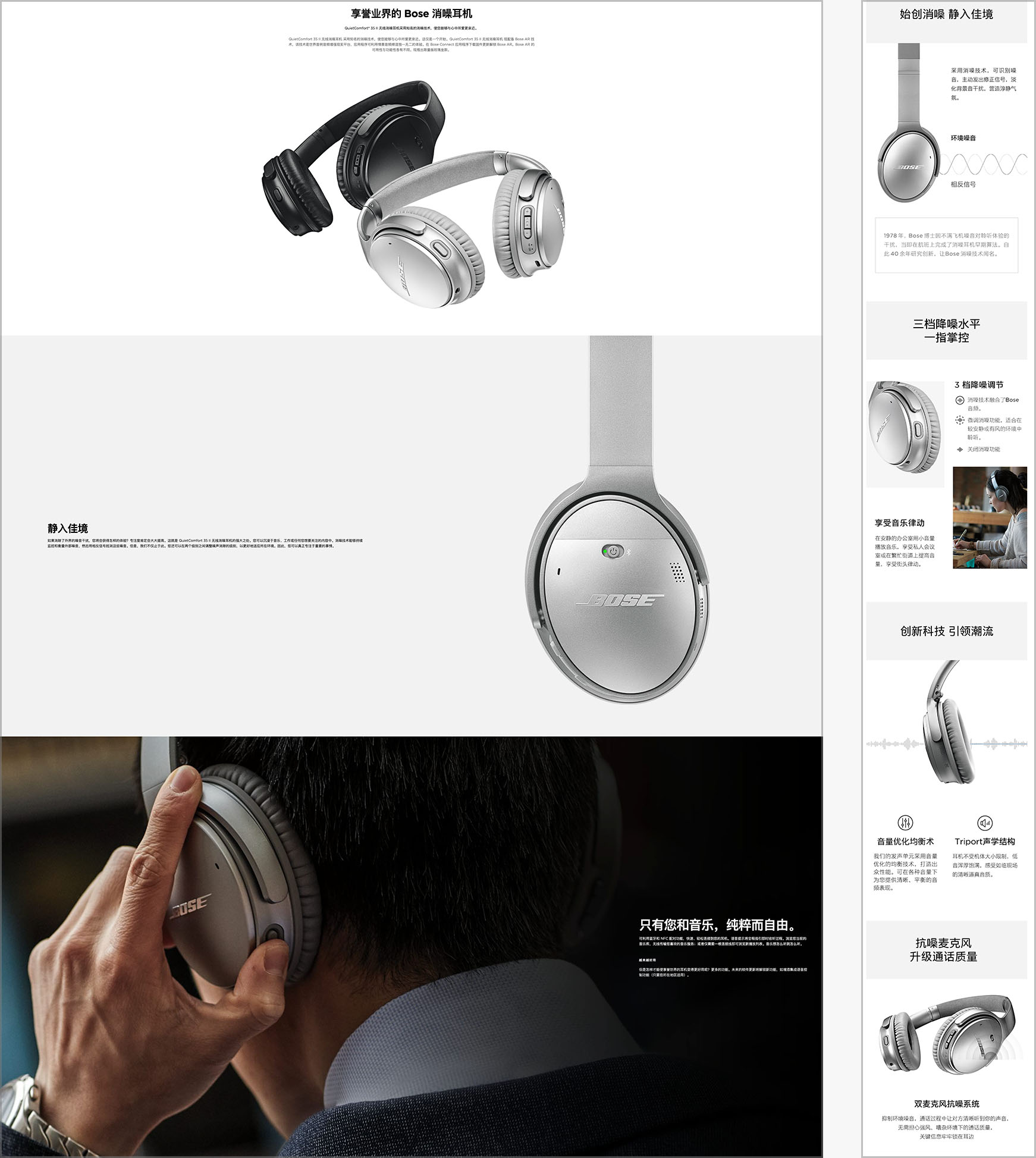

For instance, when a Chinese participant browsed the Chinese version of the Bose website during our study, he described it as a “high-end website, like those foreign brands selling luxurious products.” He didn’t want to make purchases on this website because the information density was very low compared with other Chinese retailers like Taobao and JD.

However, the site didn’t provide any purchase options, either; it only redirected people to authorized third-party shops, like the official Bose shop on JD.com. If the intention behind the Chinese Bose website was to create a luxurious brand image rather than sell products, it worked for this participant: after his experience, he believed that Bose was a luxury brand.

On the other hand, localized components can make people trust your products or services, since it shows that you spent time learning about them.

For example, another middle-aged female participant commented on the QR code featured on an Australian pharmacy website, Amcal+. “I can follow them on WeChat and get to know their deals more quickly. This increases the credibility of this website.”

The Potential Value of the Target Market

The last but most important factor that you need to consider is the potential value of the target market. Localizing your design costs much more than mere translation. It requires commitment and communication between researchers, designers, content writers, developers, and even marketing teams.

Calculating the ROI of the localization effort is crucial before deciding to localize a product instead of just hiring a translator and translating all the content. Also, prioritizing the localized components you want to add is vital. A UX roadmap can help you prioritize, plan, and coordinate the research, design, and development efforts.

Test with Your Target Audience

Even though you may have learned a lot about the culture you want to design for, you still need to remember that you’re not the user!

At the beginning of designing a cross-cultural product, conduct field studies, like contextual inquiries, with your target users. These studies can identify the role of your products or services in people’s daily lives. Observing the environment and context of use for your products and its local competitors can uncover cultural differences and potential localization directions.

Once you have your products (or prototypes) ready, conducting usability testing with international audiences can be very useful, as well. When combined with interviews, international usability testing can identify fundamental usability issues and cultural-specific practices, expectations, and mental models.

All in all, it doesn’t matter how localized a design looks if it’s hard to use. As a Chinese participant who shopped at international sites a lot stated, “The visual style doesn’t matter that much. The ease of use is the key. If my shopping experience is bad, it doesn’t matter if it looks beautiful or not.”

Tips for Crosscultural UX Design

Organizations that are just beginning to expand into a global market may want to build up international impact but may lack resources to create specific versions for every region they’ve reached. In that case, you may have to start with minimal international versions. Try the following techniques:

- Provide specific language versions that cover as many of your international audiences as possible. In the beginning, rely mostly on translation instead of localization.

- Cut down culturally specific elements to avoid possible confusion and frustration. Follow universal UX conventions. Use imagery to help shoppers navigate on ecommerce sites, for instance.

- Analyze the most valuable market and consider a design that is localized for that segment first.

When designing for a sizeable target audience with a cultural background that is different from yours, follow the steps below:

- Understand the general cultural differences. Identify the ones most relevant to your products. Based on these general differences, write down questions and assumptions to examine in subsequent research activities.

- Identify how cultural differences impact users’ interactions with your products in context. Use field studies, diary studies, and competitor analysis to identify culturally specific practices your target audience may engage in when using your products.

- Identify those product components that would benefit most from localization and prioritize them for localization. Use a combination of research data, brand-image goals, and ROI to single out those features.

- Test early and test often. Conduct usability testing with your target audience. Depending on the size of your target market, establish a professional local usability team if necessary.

References

Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations, Software of the mind (3rd. ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Edward T. Hall. 1976. Beyond culture. Anchor.

Share this article: