Facilitation is core to all successful UX workshops. However, facilitating workshops can feel daunting, especially at first. What does it mean to facilitate? What are your goals as a facilitator? What should you pay attention to? These are natural, first questions to ask as you begin your journey as a facilitator. This article walks you through the fundamentals of workshop facilitation.

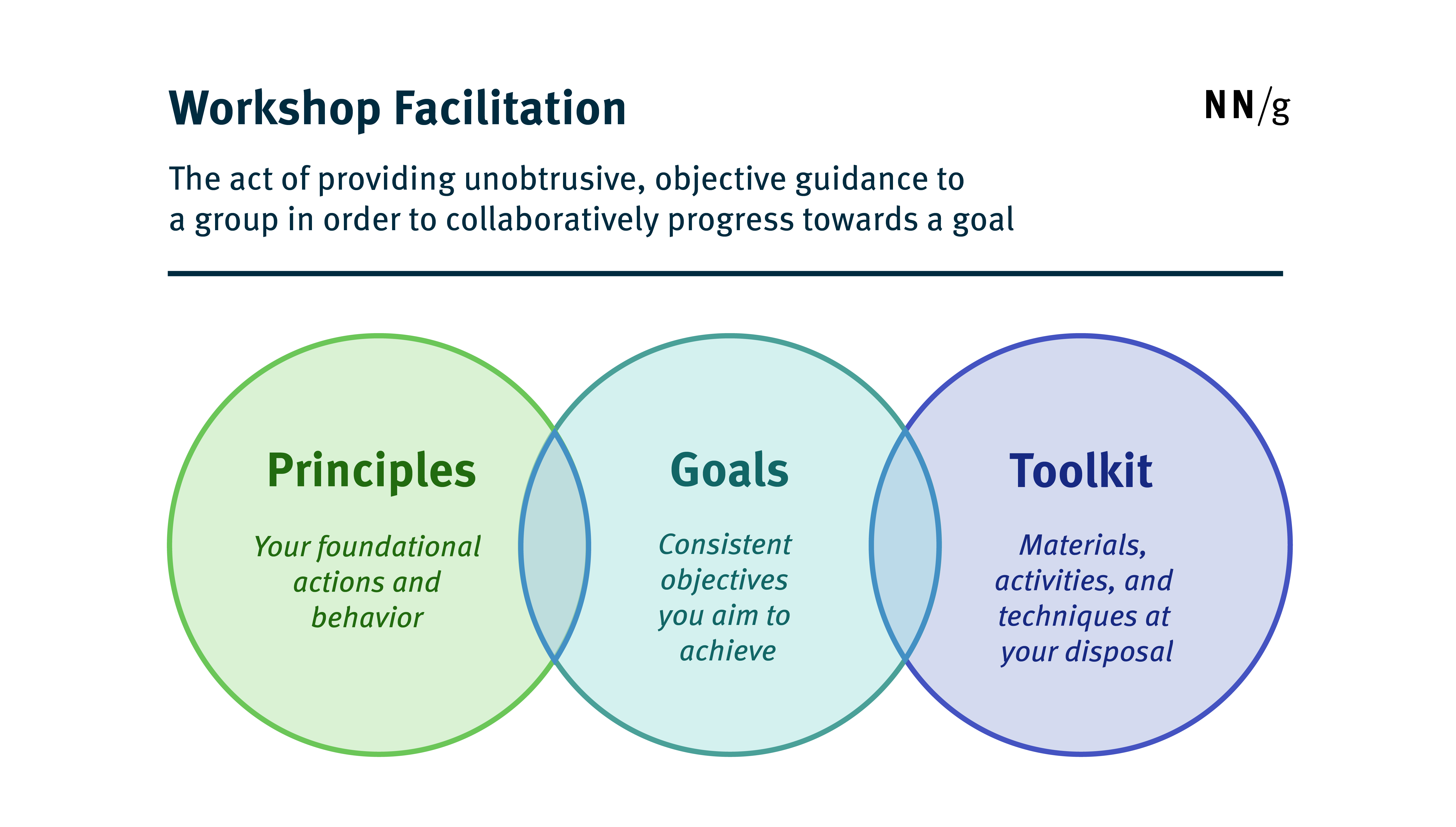

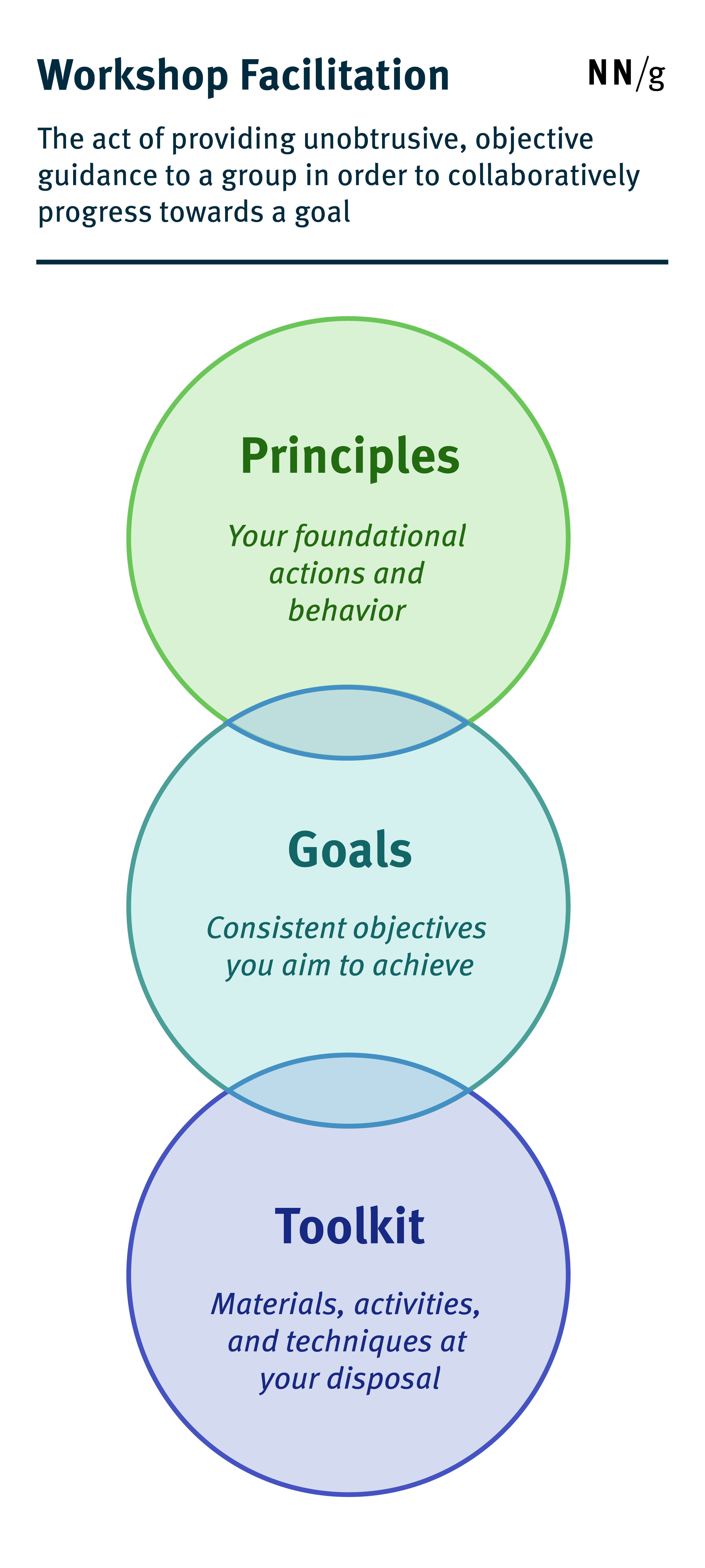

Let’s start with the definition of facilitation.

Definition: Workshop facilitation is the act of providing unobtrusive, objective guidance to a group in order to collaboratively progress towards a goal.

(Workshop facilitation should not be confused with facilitation in user research. The latter refers to interacting with the participants during a usability test or some other research activity involving users.)

The role of the facilitator is to plan and lead activities and instruction in order to help the group do their best thinking together. Facilitation does not mean taking charge and dictating the outcome, but rather allowing each participant to contribute fully and equally and enabling a shared, collaborative outcome that the group buys into. Objectivity is key; facilitators must come from a neutral place — stepping back from contributing to focus purely on the group’s process.

Your job as facilitator is not to personally generate a superbly creative idea, nor it is to make the correct decisions. Your job is to have the workshop participants create the best ideas they can and end up with the best possible decisions.

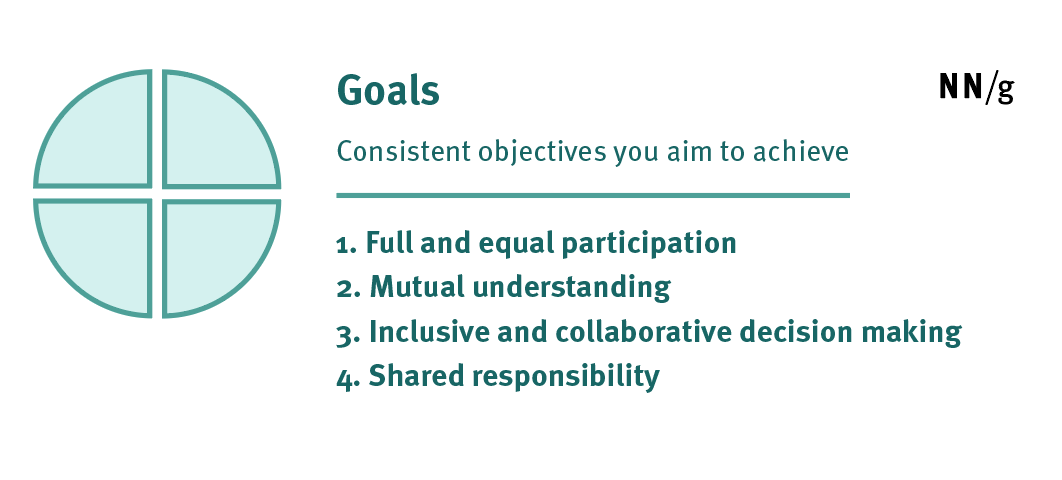

4 Facilitation Goals

When we act as facilitators, our goals are to promote:

1. Full and equal participation. Facilitators are the protectors of democracy within the group. Their duty is to make sure that each participant feels comfortable contributing. This means creating opportunities and platforms for contributors to generate their own ideas, speak up about their thoughts, and openly discuss their perspectives. This goal can be reached in many ways, most often through the diverge-and-converge technique, where participants think on their own, then share their thoughts with each other through activities lead by the facilitator.

2. Mutual understanding. It is the facilitator’s job to make sure that everyone is on the same page. We most often achieve this goal by establishing a shared language among the group, supported through the creation of tangible visuals (like empathy maps and customer-journey maps) and artifacts (like postups and dot-voting outputs).

3. Inclusive and collaborative decision making. The output of a workshop, both tangible (to-do lists and action items) and intangible (shared language and ideas), is only useful if everyone buys into it. This buy-in and accountability comes from participatory decision making —cocreating workshop outputs that everyone can get behind.

4. Shared responsibility. Facilitators help the workshop group identify who will be responsible for what upon leaving the workshop, in a way that is fair and actionable. Our goal, through activities or conversation, is for each workshop participant to have a clear idea of the next steps. This collaborative ownership is a vital component of successful workshops and drives future work.

Workshop-Facilitation Principles

Facilitation is an art, not a science. Depending on the goal of the workshop, the audience, and the dynamic, you will have to adjust your facilitation style. However, there are 6 principles that always stand true:

Always be listening. Aim to be constantly listening with an open, yet discerning mind, as participants share their ideas or thoughts. Then, if needed, guide them towards a better expression that others in the workshop can understand and build on.

Create an inviting space. Use your role as facilitator to invite all participants to contribute. Create a space (for example, introduce a break in conversation by asking everyone to pause and think for a moment or move to a postup on the wall) to accommodate people who are naturally quiet and reserved to add their perspectives. Ensure that diverse opinions are being heard, not just contributions from eager or dominant participants. Look for body language or expressions that might indicate that someone wants to speak and invite that person to participate with prompts like “Does anyone else have something to add?”, “Did you have an idea?”, or “You look like you may have something to add.”

Welcome improvisation. There is one given in facilitation and it is that no one technique will always work. The best activity or tactic depends on time, group dynamics, participant attitudes, and workshop goals. You can (and should) plan ahead, but you always need to be ready to respond to what is happening in the moment. Don’t get too stuck or comfortable doing things a certain way, but rather be ready to see what works and adapt on the go.

Be authentic to you and your knowledge. This principle is two-fold: be authentic to who you are and what you know. When facilitating, you may feel like you need to act like the stereotypical facilitator personality — outgoing and energetic. However, there is no one personality type that makes for the best facilitator. Each facilitator has her own style, from reserved to bubbly to stern and straightforward. The best style is whatever is most authentic to who you are. Second, be honest with what you know. Your job as a facilitator is to be an expert in the process, not in the content. If you don’t know something related to the content of the workshop, don’t be afraid to say so. Suggest a process or activity that can help the group answer the question at hand.

Avoid giving advice. As a facilitator, your goal is to be as objective as possible. Think of a facilitator as a referee in a sports match, ensuring the rules are abided by so everyone has an equal chance to contribute. This position puts you in a place of authority within the room. If you give advice with statements like “I would” or “if I were you,” then the workshop output and decision making will become yours, rather than the group’s. Keep any advice oriented around the process, not around the content, and use phrases like “at this point in the process I usually recommend…” or “it could be helpful to…”

Embrace constructive conflict. Conflict in the workplace is uncomfortable. While it may have a bad reputation, it is often necessary in order to establish transparency, trust, and ultimately buy-in. If conflict arises in a workshop, embrace it! Friction of any kind is simply a result of diverse personalities and opinions. A workshop is the ideal place to move through conflict, because here you have tools that can productively break down disagreement. As a facilitator, it is better to work through conflict rather than avoid it. Constructive conflict resolution can be synergistic and lead to major breakthroughs, team trust, and positive forward movement.

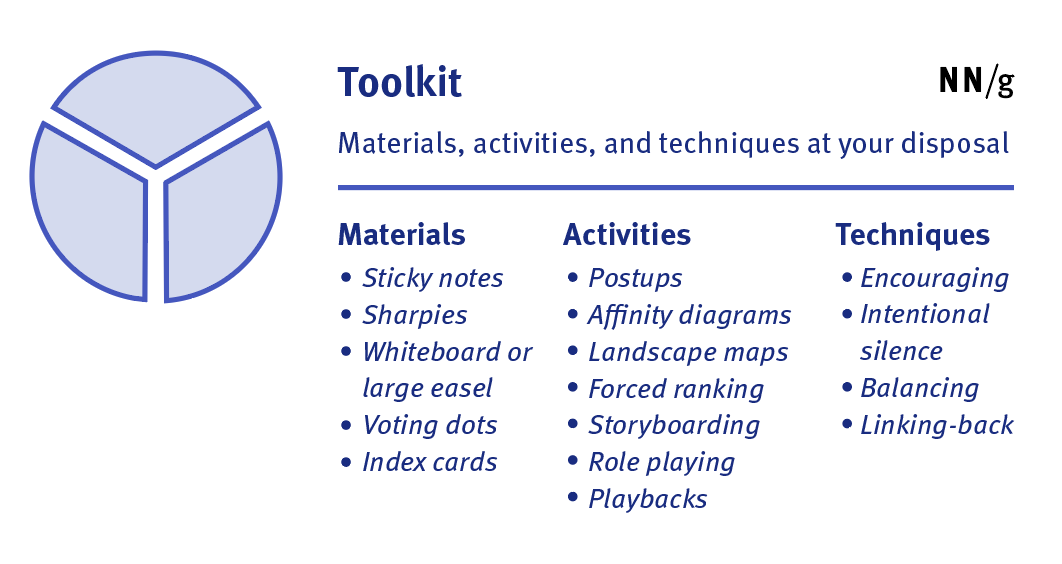

Build a Facilitation Toolkit

As you build your facilitation skills, the goal is to document the activities you use, the tactics you employ, and what works (or doesn’t). Master facilitators all reference a toolbox of methods and tricks that they can use during workshop in improvisational or planned ways.

Each time you facilitate, you have three major tools at your disposal:

Materials. These are the tangible materials you use throughout a workshop. Materials help create artifacts and capture group memory, which is vital in order to achieve our facilitation goals of equal participation and mutual understanding. They often include:

- Sticky notes

- Sharpies

- Whiteboard or large sticky notes

- Voting dots

- Index cards

Activities. Thousands of workshop exercises exist. However, few realize that at the core of each of these exercises are the same 7 foundational activities. You can combine, mix, and remix these fundamental activities to create almost any exercise needed. These core activities should be familiar tools in the facilitator’s back pocket.

- Post up

- Affinity diagramming

- Landscape mapping

- Forced ranking

- Storyboarding

- Role playing

- Playback

Techniques. These are the various (primarily verbal) tactics you can use to encourage, intervene, or maneuver conversations with or between participants. They include intentional silence (to prompt a participant to speak up in order to fill the void), balancing (asking other participants for contrary opinions or ideas), and linking (bringing tangential or unrelated participant comments back to the topic at hand).

The more you facilitate, the more robust your toolkit will become and the more comfortable you will get with the various materials, activities, and techniques. If you are beginning to build a facilitation competency within your organization, consider establishing a communal toolkit that can be a resource for current and future facilitators to use and expand.

Conclusion

There are a lot of variables at hand when you’re facilitating a workshop. The best way to improve your skills and gain confidence is through observation and practice. Observe other facilitators or offer to lend a hand as a cofacilitator. Take note of tactics that work and you would want to incorporate into your own practice.

As you begin facilitating on your own, start small, with low-stress scenarios and peers you feel comfortable with. Once you gain confidence, you can expand your practice into broad, crossdisciplinary workshops with high-visibility outputs.

If you don’t have the opportunity to facilitate in the workplace but want to improve your skills, consider volunteering as a facilitator for a nonprofit you care about. It is the best way to build confidence, learn how to adapt on the fly, and test your skillset in a low-stake environment, all the while contributing to a greater cause.

Reference

Kaner, Sam. Facilitators Guide to Participatory Decision-Making. Jossey-Bass, 2014.

Share this article: