Service design is the activity of planning and organizing a business’s resources (people, props, and processes) in order to (1) directly improve the employee’s experience, and (2) indirectly, the customer’s experience. Service blueprinting is the primary mapping tool used in the service design process.

What Is a Service Blueprint?

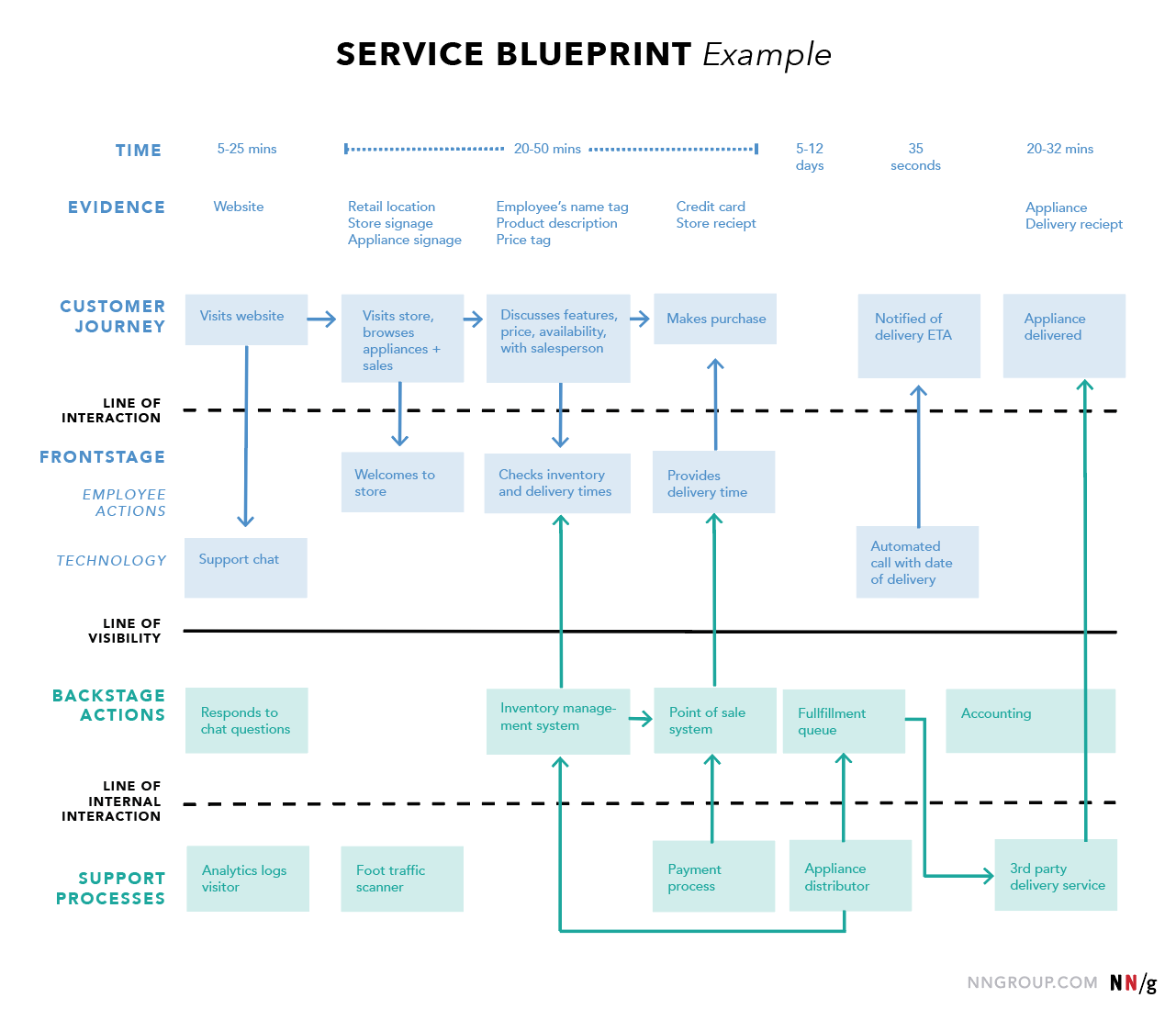

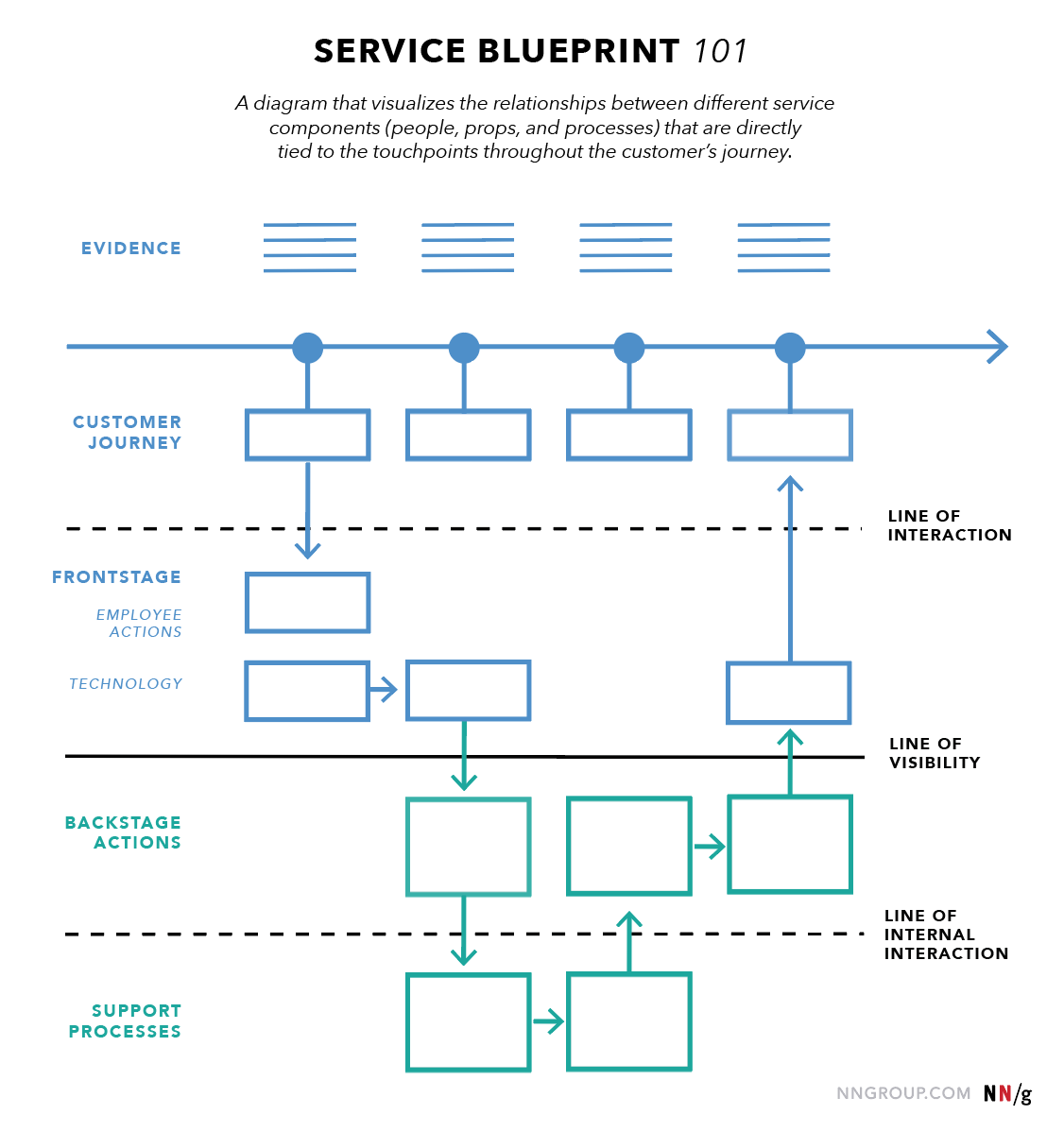

Definition: A service blueprint is a diagram that visualizes the relationships between different service components — people, props (physical or digital evidence), and processes — that are directly tied to touchpoints in a specific customer journey.

Think of service blueprints as a part two to customer journey maps. Similar to customer-journey maps, blueprints are instrumental in complex scenarios spanning many service-related offerings. Blueprinting is an ideal approach to experiences that are omnichannel, involve multiple touchpoints, or require a crossfunctional effort (that is, coordination of multiple departments).

A service blueprint corresponds to a specific customer journey and the specific user goals associated to that journey. This journey can vary in scope. Thus, for the same service, you may have multiple blueprints if there are several different scenarios that it can accommodate. For example, with a restaurant business, you may have separate service blueprints for the tasks of ordering food for takeout versus dining in the restaurant.

Service blueprints should always align to a business goal: reducing redundancies, improving the employee experience, or converging siloed processes.

Benefits of Service Blueprinting

Service blueprints give an organization a comprehensive understanding of its service and the underlying resources and processes — seen and unseen to the user — that make it possible. Focusing on this larger understanding (alongside more typical usability aspects and individual touchpoint design) provides strategic benefits for the business.

Blueprints are treasure maps that help businesses discover weaknesses. Poor user experiences are often due to an internal organizational shortcoming — a weak link in the ecosystem. While we can quickly understand what may be wrong in a user interface (bad design or a broken button), determining the root cause of a systemic issue (such as corrupted data or long wait times) is much more difficult. Blueprinting exposes the big picture and offers a map of dependencies, thus allowing a business to discover a weak leak at its roots.

In this same way, blueprints help identify opportunities for optimization. The visualization of relationships in blueprints uncovers potential improvements and ways to eliminate redundancy. For example, information gathered early on in the customer’s journey could possibly be repurposed later on backstage. This approach has three positive effects: (1) customers are delighted when they are recognized the second time — the service feels personal and they save time and effort; (2) employee time and effort are not wasted regathering information; (3) no risk of inconsistent data when the same question isn’t asked twice.

Blueprinting is most useful when coordinating complex services because it bridges crossdepartment efforts. Often, a department’s success is measured by the touchpoint it owns. However, users encounter many touchpoints throughout one journey and don’t know (or care) which department owns which touchpoint. While a department could meet its goal, the big-picture, organization-level objectives may not be reached. Blueprinting forces businesses to capture what occurs internally throughout the totality of the customer journey — giving them insight to overlaps and dependencies that departments alone could not see.

Key Elements of a Service Blueprint

Service blueprints take different visual forms, some more graphic than others. Regardless of visual form and scope, every service blueprint comprises some key elements:

-

Customer actions

Steps, choices, activities, and interactions that customer performs while interacting with a service to reach a particular goal. Customer actions are derived from research or a customer-journey map.

In the our blueprint for an appliance retailer, customer actions include visiting the website, visiting the store and browsing for appliances, discussing options and features with a sales assistant, appliance purchase, getting a delivery-date notification, and finally receiving the appliance.

-

Frontstage actions

Actions that occur directly in view of the customer. These actions can be human-to-human or human-to-computer actions. Human-to-human actions are the steps and activities that the contact employee (the person who interacts with the customer) performs. Human-to-computer actions are carried out when the customer interacts with self-service technology (for example, a mobile app or an ATM).

In our appliance company example, the frontstage actions are directly linked to customer’s actions: the store worker meets and greets customers, a chat assistant on the website informs them which units have which features, a trader partner contacts customers to schedule delivery.

Note that there is not always a parallel frontstage action for every customer touchpoint. A customer can interact directly with a service without encountering a frontstage actor, like it’s the case with the appliance delivery in our example blueprint. Each time a customer interacts with a service (through an employee or via technology), a moment of truth occurs. During these moments of truth, customers judge your quality and make decisions regarding future purchases.

-

Backstage actions

Steps and activities that occur behind the scenes to support onstage happenings. These actions could be performed by a backstage employee (e.g., a cook in the kitchen) or by a frontstage employee who does something not visible to the customer (e.g., a waiter entering an order into the kitchen display system).

In our appliance-company example, numerous backstage actions occur: A warehouse employee inputs and updates inventory numbers into the point-of-sale software; a shipping employee checks the unit’s condition and quality; a chat assistant contacts the factory to confirm lead times; employees maintain and update the company’s website with the newest units; the marketing team creates advertising material.

-

Processes

Internal steps, and interactions that support the employees in delivering the service.

This element includes anything that must occur for all of the above to take place. Processes for the appliance company include credit-card verification, pricing, delivery of units to the store from the factory, writing quality tests, and so on.

In a service blueprint, key elements are organized into clusters with lines that separate them. There are three primary lines:

- The line of interaction depicts the direct interactions between the customer and the organization.

- The line of visibility separates all service activities that are visible to the customer from those that are not visible. Everything frontstage (visible) appears above this line, while everything backstage (not visible) appears below this line.

- The line of internal interaction separates contact employees from those who do not directly support interactions with customers/users.

The last layer of a service blueprint is evidence, which is made of the props and places that anyone in the blueprint has an exchange with. Evidence can be involved in both frontstage and backstage processes and actions.

In our appliance example, evidence includes the appliances themselves, signage, physical stores, website, tutorial video, or email inboxes.

Secondary Elements to Include in a Service Blueprint

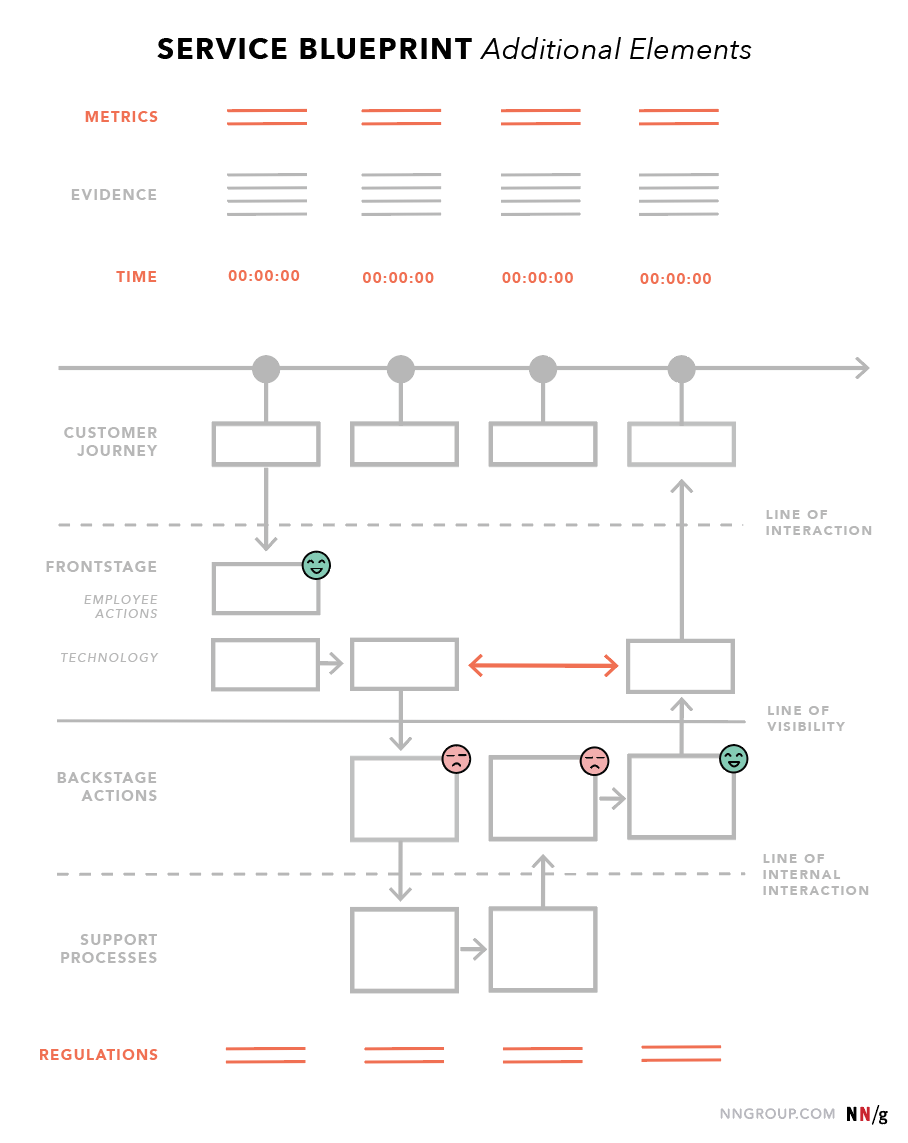

Blueprints can be adapted to context and business goals by introducing the additional elements as needed:

Arrows

Arrows are a key element of service blueprinting. They indicate relationships, and more importantly, dependencies. A single arrow suggests a linear, one-way exchange, while a double arrow suggests the need for agreement and codependency.

Time

If time is a primary variable in your service, an estimated duration for each customer action should be represented in your blueprint.

Regulations or Policy

Any given policies or regulations that dictate how a process is completed (food regulations, security policies, etc.) can be added to your blueprint. This information will allow us to understand what can and cannot be changed as we optimize.

Emotion

Similar to how a user’s emotion is represented throughout a customer-journey map, employees’ emotions can be represented in the blueprint. (Emotion is shown through the green and red faces in the example below.) Where are employees frustrated? Where are employees happy and motivated? If you already have some qualitative data regarding points of frustration (possibly obtained from internal surveys or other methods), you can use them in the blueprint to help focus the design process and more easily locate pain points.

Metrics

Any success metric that can provide context to your blueprint is a benefit, especially if buy-in is the blueprint’s goal. An example may be the time spent on various processes, or the financial costs associated with them. These numbers will help the business identify where time or money are wasted due to miscommunication or other inefficiencies.

Conclusion

Service blueprints are companions to customer-journey maps: they help organizations see the big picture of how a service is implemented by the company and used by the customers. They pinpoint dependencies between employee-facing and customer-facing processes in the same visualization and are instrumental in identifying pain points, optimizing complex interactions, and ultimately saving money for the organization and improving the experience for its customers.

To learn more, check out our full day course Service Blueprinting.

Share this article: