History of Design Thinking

It is a common misconception that design thinking is new. Design has been practiced for ages: monuments, bridges, automobiles, subway systems are all end-products of design processes. Throughout history, good designers have applied a human-centric creative process to build meaningful and effective solutions.

In the early 1900's husband and wife designers Charles and Ray Eames practiced “learning by doing,” exploring a range of needs and constraints before designing their Eames chairs, which continue to be in production even now, seventy years later. 1960's dressmaker Jean Muir was well known for her “common sense” approach to clothing design, placing as much emphasis on how her clothes felt to wear as they looked to others. These designers were innovators of their time. Their approaches can be viewed as early examples of design thinking — as they each developed a deep understanding of their users’ lives and unmet needs. Milton Glaser, the designer behind the famous I ♥ NY logo, describes this notion well: “We’re always looking, but we never really see…it’s the act of attention that allows you to really grasp something, to become fully conscious of it.”

Despite these (and other) early examples of human-centric products, design has historically been an afterthought in the business world, applied only to touch up a product’s aesthetics. This topical design application has resulted in corporations creating solutions which fail to meet their customers’ real needs. Consequently, some of these companies moved their designers from the end of the product-development process, where their contribution is limited, to the beginning. Their human-centric design approach proved to be a differentiator: those companies that used it have reaped the financial benefits of creating products shaped by human needs.

In order for this approach to be adopted across large organizations, it needed to be standardized. Cue design thinking, a formalized framework of applying the creative design process to traditional business problems.

The specific term "design thinking" was coined in the 1990's by David Kelley and Tim Brown of IDEO, with Roger Martin, and encapsulated methods and ideas that have been brewing for years into a single unified concept.

What — Definition of Design Thinking

Design thinking is an ideology supported by an accompanying process. A complete definition requires an understanding of both.

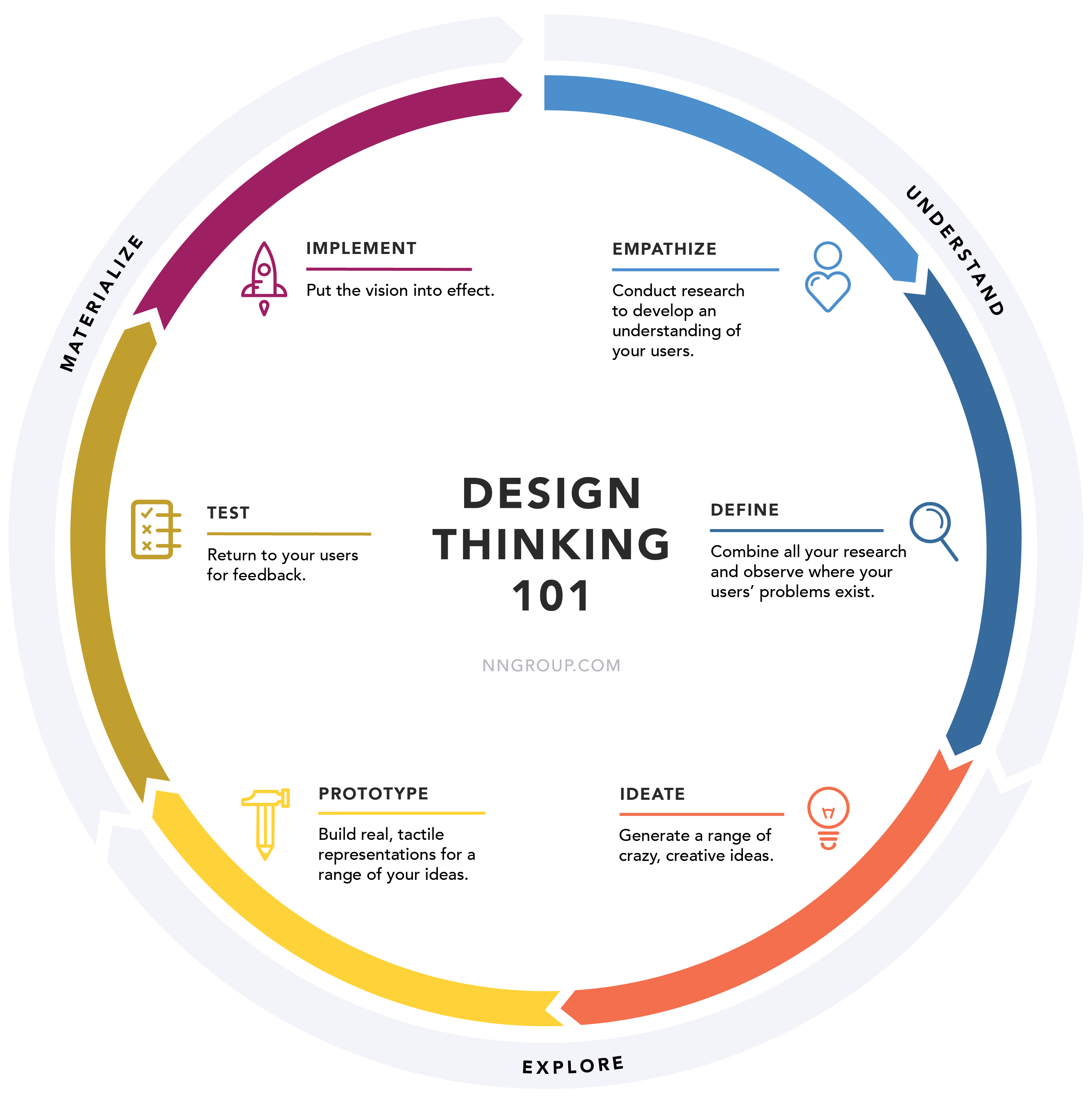

Definition: The design thinking ideology asserts that a hands-on, user-centric approach to problem solving can lead to innovation, and innovation can lead to differentiation and a competitive advantage. This hands-on, user-centric approach is defined by the design thinking process and comprises 6 distinct phases, as defined and illustrated below.

How — The Process

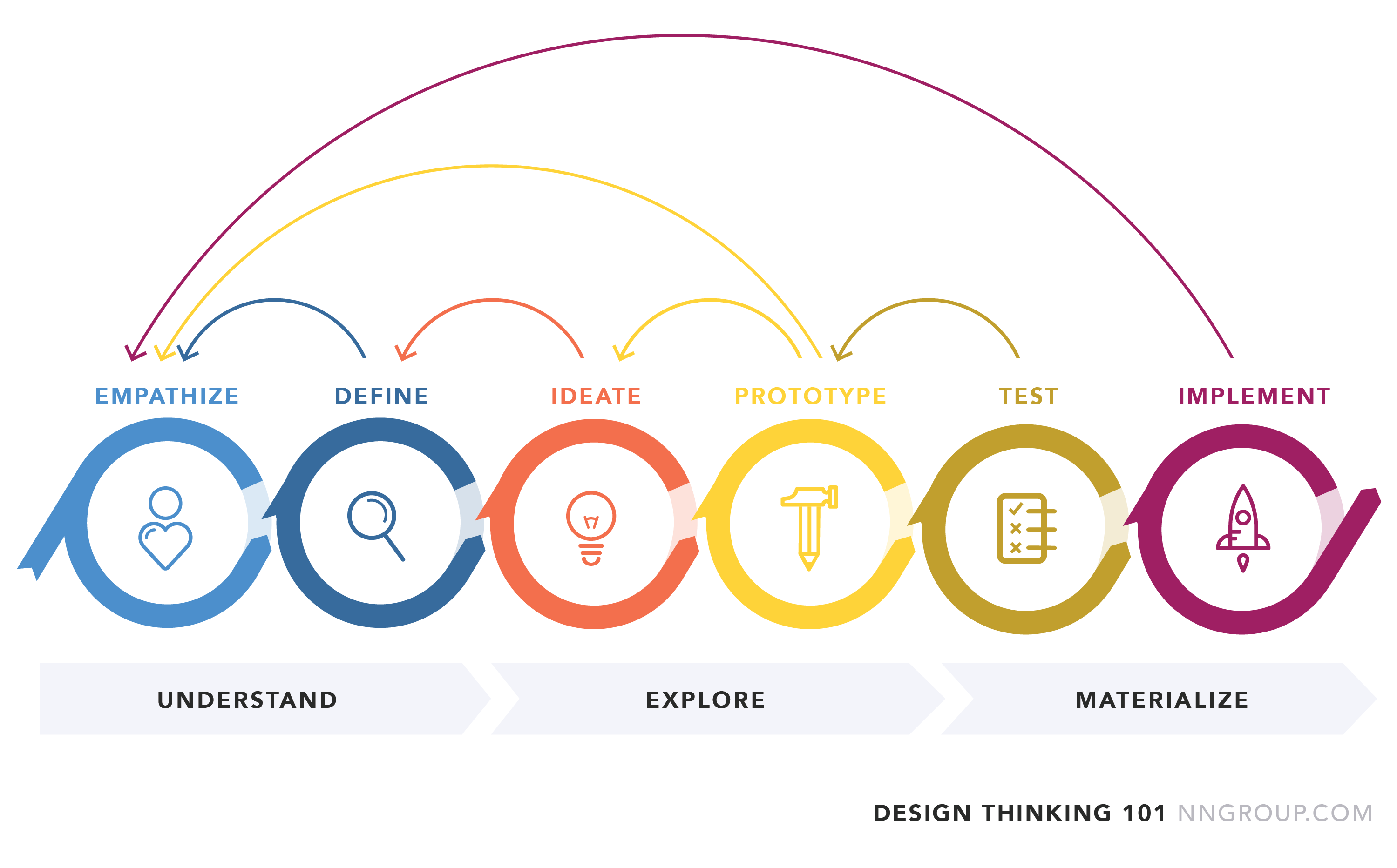

The design-thinking framework follows an overall flow of 1) understand, 2) explore, and 3) materialize. Within these larger buckets fall the 6 phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement.

Empathize: Conduct research in order to develop knowledge about what your users do, say, think, and feel.

- Imagine your goal is to improve an onboarding experience for new users. In this phase, you talk to a range of actual users. Directly observe what they do, how they think, and what they want, asking yourself things like ‘what motivates or discourages users?’ or ‘where do they experience frustration?’ The goal is to gather enough observations that you can truly begin to empathize with your users and their perspectives.

Define: Combine all your research and observe where your users’ problems exist. In pinpointing your users’ needs, begin to highlight opportunities for innovation.

- Consider the onboarding example again. In the define phase, use the data gathered in the empathize phase to glean insights. Organize all your observations and draw parallels across your users’ current experiences. Is there a common pain point across many different users? Identify unmet user needs.

Ideate: Brainstorm a range of crazy, creative ideas that address the unmet user needs identified in the define phase. Give yourself and your team total freedom; no idea is too farfetched and quantity supersedes quality.

- At this phase, bring your team members together and sketch out many different ideas. Then, have them share ideas with one another, mixing and remixing, building on others' ideas.

Prototype: Build real, tactile representations for a subset of your ideas. The goal of this phase is to understand what components of your ideas work, and which do not. In this phase you begin to weigh the impact vs. feasibility of your ideas through feedback on your prototypes.

- Make your ideas tactile. If it is a new landing page, draw out a wireframe and get feedback internally. Change it based on feedback, then prototype it again in quick and dirty code. Then, share it with another group of people.

Test: Return to your users for feedback. Ask yourself ‘Does this solution meet users’ needs?’ and ‘Has it improved how they feel, think, or do their tasks?’

- Put your prototype in front of real customers and verify that it achieves your goals. Has the users’ perspective during onboarding improved? Does the new landing page increase time or money spent on your site? As you are executing your vision, continue to test along the way.

Implement: Put the vision into effect. Ensure that your solution is materialized and touches the lives of your end users.

- This is the most important part of design thinking, but it is the one most often forgotten. As Don Norman preaches, “we need more design doing.” Design thinking does not free you from the actual design doing. It’s not magic. Milton Glaser’s words resonate: “There’s no such thing as a creative type. As if creativity is a verb, a very time-consuming verb. It’s about taking an idea in your head, and transforming that idea into something real. And that’s always going to be a long and difficult process. If you’re doing it right, it’s going to feel like work.” As impactful as design thinking can be for an organization, it only leads to true innovation if the vision is executed. The success of design thinking lies in its ability to transform an aspect of the end user’s life. This sixth step — implement — is crucial.

Why — The Advantage

Why should we introduce a new way to think about product development? There are numerous reasons to engage in design thinking, enough to merit a standalone article, but in summary, design thinking achieves all these advantages at the same time:

- It is a user-centered process that starts with user data, creates design artifacts that address real and not imaginary user needs, and then tests those artifacts with real users.

- It leverages collective expertise and establishes a shared language and buy-in amongst your team.

- It encourages innovation by exploring multiple avenues for the same problem.

Jakob Nielsen says “a wonderful interface solving the wrong problem will fail." Design thinking unfetters creative energies and focuses them on the right problem.

Flexibility — Adapt to Fit Your Needs

The above process will feel abstruse at first. Don’t think of it as if it were a prescribed step-by-step recipe for success. Instead, use it as scaffolding to support you when and where you need it. Be a master chef, not a line cook: take the recipe as a framework, then tweak as needed.

Each phase is meant to be iterative and cyclical as opposed to a strictly linear process, as depicted below. It is common to return to the two understanding phases, empathize and define, after an initial prototype is built and tested. This is because it is not until wireframes are prototyped and your ideas come to life that you are able to get a true representation of your design. For the first time, you can accurately assess if your solution really works. At this point, looping back to your user research is immensely helpful. What else do you need to know about the user in order to make decisions or to prioritize development order? What new use cases have arisen from the prototype that you didn’t previously research?

You can also repeat phases. It’s often necessary to do an exercise within a phase multiple times in order to arrive at the outcome needed to move forward. For example, in the define phase, different team members will have different backgrounds and expertise, and thus different approaches to problem identification. It’s common to spend an extended amount of time in the define phase, aligning a team to the same focus. Repetition is necessary if there are obstacles in establishing buy-in. The outcome of each phase should be sound enough to serve as a guiding principle throughout the rest of the process and to ensure that you never stray too far from your focus.

Scalability — Think Bigger

The packaged and accessible nature of design thinking makes it scalable. Organizations previously unable to shift their way of thinking now have a guide that can be comprehended regardless of expertise, mitigating the range of design talent while increasing the probability of success. This doesn’t just apply to traditional “designery” topics such as product design, but to a variety of societal, environmental, and economical issues. Design thinking is simple enough to be practiced at a range of scopes; even tough, undefined problems that might otherwise be overwhelming. While it can be applied over time to improve small functions like search, it can also be applied to design disruptive and transformative solutions, such as restructuring the career ladder for teachers in order to retain more talent.

Conclusion

We live in an era of experiences, be they services or products, and we’ve come to have high expectations for these experiences. They are becoming more complex in nature as information and technology continues to evolve. With each evolution comes a new set of unmet needs. While design thinking is simply an approach to problem solving, it increases the probability of success and breakthrough innovation.

Learn more about design thinking in the full-day course Generating Big Ideas with Design Thinking.

Download the illustrations from this article from the link below in a high-resolution version that you can print as a poster or any desired size.

Share this article: