Two years ago, we began a long-term research project to better understand design thinking: how practitioners incorporate it into everyday work and its effects on project outcomes.

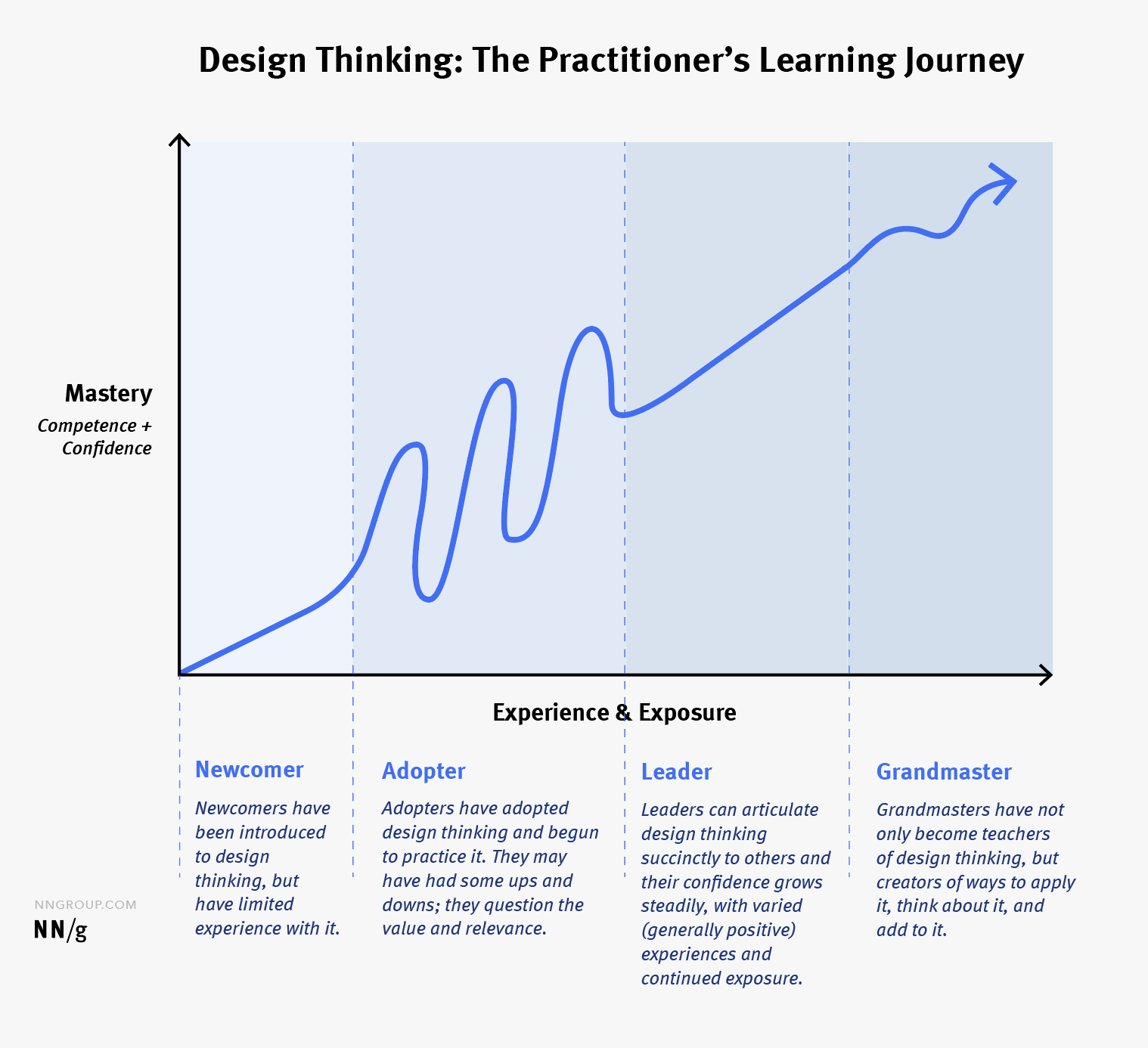

In setting out to define a design-thinking maturity model, we realized that the maturity of the individual team members and their experience, exposure, and mastery of design thinking were essential to the overall team’s (or organization’s) ability to effectively utilize design-thinking methodologies. To better understand this relationship between individual abilities and team performance, we identified catalysts—individual practitioners whose design-thinking mastery positively influenced design-thinking practices in their teams or organizations. Based on our conversations with these catalysts about their experience (and the experience of those they teach and guide), we hypothesized that design-thinking practitioners share roughly the same learning journey, despite different backgrounds and contexts.

To clarify the stages of this learning journey, we conducted a large-scale survey involving 1067 practitioners and aimed at investigating respondents’ experience with design thinking. We classified responses into potential learning stages based on the self-reported design-thinking exposure, experience, primary activities, and biggest challenges. This process, combined with talking to hundreds of design-thinking practitioners each year at our UX Conference, helped us establish a set of unifying stages that most practitioners encounter while learning design thinking: newcomer, adopter, leader, and grandmaster.

Why These Stages Matter

As a practitioner, you can better understand your own learning process and set appropriate expectations if you know the typical stages of your learning journey.

- Most learning journeys feel frustrating at some point. Having insight into the design-thinking learning journey and what you’re working towards can provide encouragement during “what’s the point” moments. If you’re learning design thinking by yourself, awareness of the journey can help you feel less alone.

- Identifying your current phase can help you predict future progress. Stay focused on the goals of your current learning phase rather than jumping ahead. Jumping ahead runs the risk of creating experiences that leave you feeling doubtful or confused, and thus less motivated to continue to learn.

As an educator (or manager or mentor), you empathize, create an effective design-thinking learning experience for others, and enable sustainable, long-term success.

- Understanding where others are and that different people will be at different stages in the learning process is a key part in being an effective educator. It allows you to deliver effective learning experiences without overwhelming your audience with too much complexity and also preemptively mitigate learners’ pain points at each phase.

- Educating and activating a group of people takes a lot of resources (time, money, and effort). This education process should intentionally designed, in order to maximize resources and return on investment. Mapping participants’ phases and their progression through the learning journey allows an educator to benchmark progress, and indirectly, success of the training.

As practitioners progress through the stages, their mastery increases in a nonlinear fashion—experiencing fluctuations due especially to lack of self-confidence. Note that mastery is a combination of competence and confidence; both are required to effectively use design thinking. If you are good but feel insecure, you won’t deviate from the strict steps of design thinking and won’t teach others. The goal is to create alignment between competence and confidence in order to master design thinking.

Framework

Rather than thinking of each phase as a discrete checklist, we’ve created a three-component framework for characterizing each learning stage: criteria, primary activities, and educator goals.

- Criteria are observable qualities that can help the learner (or an external observer, such as an educator) identify the learner’s current stage in the learning journey. They include awareness of one’s own competence, level of exposure, and confidence.

- Primary activities are the learner’s actions and use of design-thinking methodologies.

- Educator goals and obstacles summarize learner’s pain points at any given stage and corresponding educator goals that can help learners overcome them.

Phase 1: Newcomer

This phase is the first in the learning journey. For the majority of practitioners, this exposure occurs via a university or institution, a place of work, or an online resource. The amount of time spent at this first stage depends on how motivated the learner is. Many practitioners immediately perceive design thinking as useless and never leave this stage.

Criteria

Individuals in this stage have been introduced to design thinking, but have limited experience with it. Practitioners in this phase fall into 2 buckets:

- Individuals who are committed to learn design thinking

- Individuals who are not interested to learn more about design thinking. They’ve been exposed to design thinking, but that is where their learning journey halts. These practitioners may remain in this stage indefinitely until they encounter a deeper exposure to design thinking that broadens their perspective, experience, or acceptance.

Newcomers’ knowledge is minimal; they have a surface-level understanding of design thinking, often rooted in the definition they received during their first exposure. They may be able to provide a definition but are not familiar with the details of a framework or its value. They have topical associations with design thinking—sticky-notes, the infinity loop, whiteboards. Newcomers are unaware of their design-thinking incompetence — they don’t yet know what they don’t know.

Primary Activities

Newcomers’ primary goal is to understand the basics — what design thinking is and why it’s useful. Often, this stage’s activities are self-initiated: browsing articles, reading books, or signing up for a seminar. In other cases, design thinking is learned by necessity or requirement at work or school through onboarding programs, collaborative workshops, required courses, or mandated trainings. Most newcomers have not yet actively practiced design-thinking activities, or if they have their participation is shallow and topical.

Educator’s Goals and Obstacles

The goal of a design thinking teacher at this stage is to communicate the purpose and potential value of design thinking and motivate the newcomer to pursue learning, then make time for it and move on to the next phases. Common educator obstacles are overcoming learners’ negative sentiments: annoyance with “yet another thing to learn,” unsuccessful previous attempts or experiences, capped bandwidth, and realization of their own limits (in this case, how little they know about design thinking).

Phase 2: Adopter

Individuals at this stage have adopted design thinking and begun to practice it. They may have had some ups and downs in their limited experience with design thinking. It is common for adopters to waffle between overconfidence and self-doubt and to feel both confused and successful at the same time. Successful adopters see design thinking relevant to their work or life and, thus, make a commitment to continue learning.

Criteria

Increased (passive or active) exposure and familiarity with design thinking has made adopters aware of their knowledge limits. They understand the potential of design thinking, but still have a lot to learn. Adopters have invested time, effort, and energy into design thinking and have started applying design thinking to their work with mixed success. Their commitment to design thinking can be self-initiated or dictated to them by an authority with an invested interest (company leadership, university, or boss).

Primary Activities

Adopters practice design thinking in a linear way — by the book. They rely heavily on checklists — for the 6 design-thinking steps, as well as for the activities associated with each of those steps. Many adopters lean towards a prescribed, branded version of design thinking, often provided by their institution, company, or a reputable external organization.

It is common for practitioners to encounter failure in this phase —especially if they are learning predominately on their own—because of their incomplete understanding of the design-thinking framework. Common types of failure include jumping to conclusions, using the wrong activity at the wrong time, and lack of buy-in or support from others. These failures push some practitioners to abandon design thinking altogether. However, most learning in this phase occurs through failure. Practitioners who embrace failure tend to develop a malleable understanding of design thinking in future phases. (It’s a cliché, but it’s a cliché because it’s right: failure is a learning opportunity.)

Some adopters might learn primarily by actively participating in design-thinking workshops and activities together with experienced design-thinking practitioners. While this group of adopters may not have the opportunity to experience a sense of failure because of the support received from their peers, it is still likely they will question the value and legitimacy of design thinking at some point.

Educator’s Goals and Obstacles

Adopters are on the bike, but still need training wheels and coaching. Adopters’ confidence drops as they realize the indirect ways in which design thinking can be applied and how much they have to learn — for example, how straightforward they originally thought the process was versus how abstract (and potentially overwhelming) it really is. The goal of the educator at this stage is to help learners through hands-on practice and assistance until they can comfortably use design thinking on their own. Individuals are most commonly lost in this phase when they cannot make a direct connection to the relevance of design thinking. Thus, it is imperative that adopters find relevance and application to their everyday work.

Phase 3: Leader

This is the proficiency stage of design thinking. Leaders can articulate design thinking succinctly to others and their confidence grows steadily, with varied (generally positive) experiences and continued exposure. Leaders take an active, independent role in their learning journey and begin to think adaptively about design thinking; they start to explore new applications and may even be known for design thinking within their circle.

Criteria

Leaders can practice design thinking with general ease, confidence, and independence. Leaders become more and more aware of their new knowledge and comfort as they mature through this phase. They often teach others earlier in the learning journey. They are able to consistently and somewhat adaptively perform design-thinking activities without thinking about them. They don’t try to apply design thinking by the book, rather use it as needed depending on their goal.

Primary Activities

Practitioners in this phase lead design-thinking activities with others or perform design thinking without coaching, but still with some preparation and focus. While they were previously participants, they now facilitate, initiate, and even advocate for collaborative design-thinking activities. For example, they might initiate an empathy building workshop, pull others into user research, or map a user journey to uncover pain points or moments of truth. These activities that leaders are involved in gradually increase in complexity, ranging from involving users in workshops to fostering stakeholders into the process and multimedium prototyping (for example, bodystorming, future-state blueprinting, and storyboards) .

Educator’s Goals and Obstacles

The goal of the teacher in this phase is to continue to instill confidence and help sustain the learner’s commitment. The goal should be to empower leaders to transition into the role of design-thinking teachers and facilitators. As much as they’ve progressed, they still may not be aware of weaknesses or potential improvements (even though they often recognize a mistake after they made it). Promoting reflection in this phase is the key to helping leaders continue to grow (and progress to grandmasters). They must take an active role in adapting the design-thinking practice to fit their contextual goals and needs, be sustainable over time, and maximize potential benefits.

Phase 4: Grandmaster

(The term grandmaster comes from the game of chess. It’s a title given to only the best and most exceptional players, who have spent countless hours practicing and honing their techniques.)

Practitioners at this stage have not only become teachers of design thinking, but create new ways of applying it, thinking about it, and adding to it. The practice of design thinking is so embodied in their behavior that they seldom have to think about applying it. Grandmasters view design thinking as a flexible, dynamic toolkit. They’ve long departed from the concept of a prescribed process and rather view it as scaffolding to solve both organizational (often internal) and end-user (external, product-related) problems. However, this phase doesn’t come without downsides. Grandmasters are more likely to doubt design thinking than leaders, often when early-stage learners fall victim to mismanaged design-thinking marketing and thus misinterpret, misapply, or undercut the practice as a whole.

Criteria

Grandmasters’ defining characteristic is the ability to critically reflect on their design-thinking practice. This reflection enables them to judge what is useful and potentially depart from the traditional ways and activities of design thinking. Grandmasters also know how to help others to this same stage of enlightenment. Grandmasters are aware of their competence. They have an in-depth, intuitive understanding and can blend design-thinking skills together to meet their specific need.

Primary Activities

Traditional design-thinking activities are still used by grandmasters, but are altered, adapted, and applied in complex ways, depending on the goal, audience, and potential obstacles. Grandmasters don’t stick to prescribed or branded versions of design thinking and more often pull tools and/or activities from other realms, like service design and business strategy. For example, grandmasters are more likely to use activities such as service blueprinting and business-model canvassing. While basic design thinking activities are still carried out in this phase, they differ from those in earlier stages because they are inputs or alignment strategies for more complex, involved activities (compared to previous stages where the basic activities are the end goal).

Educator’s Goals and Obstacle

Grandmasters have very likely surpassed their original teachers. Their goal becomes not just activating and educating individual learners, but rather organizations as a whole. As practitioners themselves, grandmasters face an increasing likelihood of (re)questioning the value of design thinking. Increased knowledge and mastery are a blessing and curse; this pessimistic view is often rooted in the realization of what design thinking can and cannot solve (contrary to earlier naive ideas that design thinking can be a cure-all). However, even grandmasters can get better, by self-reflection, by learning from their peers, and also by learning from their juniors: one of the skills of supreme mastery is the ability to discern which of the hundreds of ideas generated by eager newcomers is actually a stroke of genius.

Additional Notes and Considerations

- Trained designers experience the design-thinking learning journey too, just differently. Many designers view design thinking as simply a way to articulate and communicate a “designerly” approach to problem solving. Thus, many designers are likely to feel as if they bypassed this learning journey altogether because this is how they instinctively think. However, designers experience this learning journey too, albeit much earlier in their education or career, and likely not packaged or branded as design thinking. This does not mean that all grandmasters are designers, but rather that many successful designers likely are.

- One person may be at multiple levels at the same time. Some skills may fall into one phase, while others into a lower different phase. For example, a practitioner’s mindset and reflection may fall into Grandmaster, while their hands-on experience and exposure to activities into Leader. The goal is to identify this imbalance and invest in experiences that bolster weaker dimensions of our practice.

Conclusion

The design-thinking learning journey is a high-level, distilled representation of the most common learning phases observed in our research. Learning and teaching design thinking is messy; not all experiences will fit squarely into this model.

Regardless, it is imperative we frame and articulate learning design thinking as an experiential journey. Doing so can help us become more effective learners and educators. Learners can gain insight and awareness into the greater journey and goals, while educators can thoughtfully and successfully execute the design-thinking learning experience they aim to create.

Share this article: