A diary study is a research method used to collect qualitative data about user behaviors, activities, and experiences over time. In a diary study, data is self-reported by participants longitudinally — that is, over an extended period of time that can range from a few days to even a month or longer. During the defined reporting period, study participants are asked to keep a diary and log specific information about activities being studied. To help participants remember to fill in their diary, sometimes they are periodically prompted (for example, through a notification received daily or at select times during the day).

The context and time period in which data is collected for a diary study make them unlike other common user-research methods, such as surveys (which are designed to collect self-reported information about a user’s habits and experiences outside of the context of the scenarios being studied), or usability tests (which yield observational information about a specific moment or planned set of confined interactions in a lab setting). They are the “poor man’s field study”: they are unlikely to provide observations that are as rich or detailed as a true field study, but they can serve as a decent approximation.

When to Conduct a Diary Study

If you’re looking for a contextual understanding of user behaviors and experiences over time, it can be very difficult to appropriately create scenarios in a lab setting to gather these kind of insights. Diary studies are useful for understanding long-term behaviors such as:

- Habits — What time of day do users engage with a product? If and how they choose to share content with others?

- Usage scenarios — In what capacity do users engage with a product? What are their primary tasks? What are their workflows for completing longer-term tasks? (These scenarios can be used for user testing later in the process.)

- Attitudes and motivations — What motivates people to perform specific tasks? How are users feeling and thinking?

- Changes in behaviors and perceptions — How learnable is a system? How loyal are customers over time? How do they perceive a brand after engaging with the corresponding organization?

- Customer journeys — What is the typical customer journey and cross-channel user experience as customers interact with your organization using different devices and channels such as, email, phone, websites, mobile applications, kiosks, social media, and online chat? What is the cumulative effect of multiple service touchpoints?

The focus of a diary study can range from very broad to extremely targeted, depending on the topic being studied. Diary studies are often structured to focus on one of the following topic scopes:

- Product or Website — Understanding all interactions with a site (e.g., an intranet) over the course of a month.

- Behavior — Gathering general information about user behavior (e.g., smartphone usage, college-student web-visitation patterns)

- General activity — Understanding how people complete general activities (e.g., sharing information via social tools or shopping online)

- A specific activity — Understanding how people complete specific activities (e.g., buying a new car or planning a vacation)

Methodology

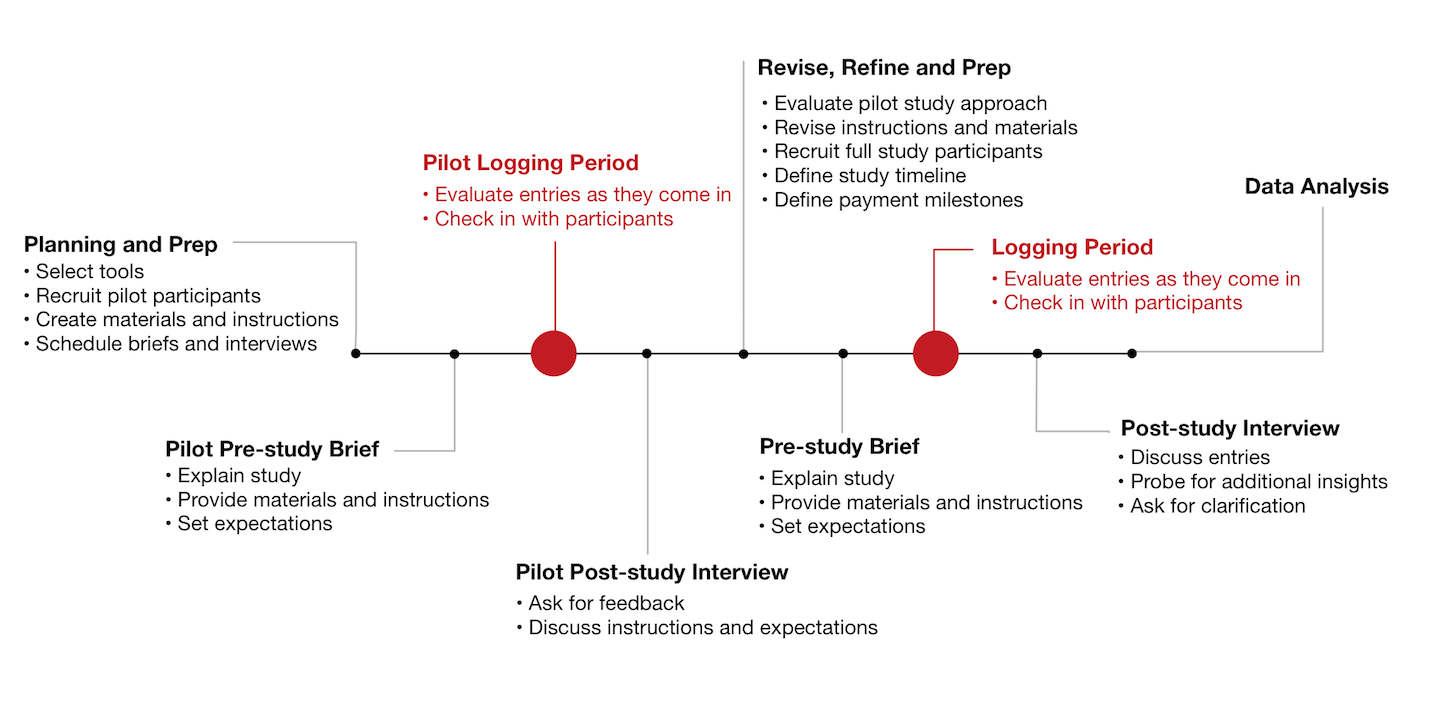

A diary study is typically composed of five phases:

- Planning and Preparation. Define the focus of the study and the long-term behaviors that you need to understand. Define a timeline, select tools for participants to report data, recruit participants, and prepare instructions or support materials.

- Prestudy brief. Take time up front to get participants ready to log. Schedule a face-to-face meeting or phone call with each participant to discuss the details of the study. Walk through the schedule or calendar for the reporting period and discuss expectations. Discuss the tools they will be using and be sure each participant has familiarized themselves with the technology; answer any questions they may have before beginning.

- Logging period. To support effective activity logging, provide a simple framework. Be as specific as possible about what information you need participants to log, without stifling natural variability and differences that you cannot plan for. (Discovering the unexpected is after all one of the primary reasons to do user research.) Create clear and detailed instructions for logging. Give users example log entries to help them understand the level of detail you need from them. (But make sure you don’t bias participants toward those types of entries that you happened to provide as examples.)

There are two common techniques researchers employ to collect diary data from participants.- In-Situ Logging — This method is the most straightforward method to collect data. Participants are asked to log information about relevant activities in the situation they occur (or in situ). When participants engage in a relevant activity, they must report all important details about that activity right away. Since this technique requires participants to take the time to report this information at the time of the event, this technique is best reserved for situations when you don’t foresee a large volume of diary entries occurring or if the context is such that participant’s daily activities will not be adversely effected by logging in situ. In-situ logging is best supported by channels and devices that can handle structured long-form text entry such as, email, web-form questionnaires, traditional paper diaries, or digital customer-insight tools such as FocusVision or 7daysinmylife. Audio or video diaries are also great tools for participants, but the output may need to be transcribed for analysis.

- Snippet Technique — Another popular, less intrusive method for logging activities is the snippet technique. With this technique, participants only record short snippets of information about activities as they occur. Then, at the end of each day, or when participants have time, they elaborate on each snippet by providing additional details about the activity. This 2-step technique ensures that relevant information is captured in situ, before being forgotten but without requiring participants to provide extensive detail at the time of capture, which can be intrusive and unnatural in certain situations. Common channels for study participants to report snippets to researchers include email, text message, Twitter, or Facebook. These channels are widely familiar for short-form communication. Participants are encouraged to use their mobile phones to report events as they happen, since these devices are accessible. Expanding upon reported snippets can be accomplished with the channels and tools mentioned above for more in-depth reporting. Consider asking participants to expand on their snippets by filling out a questionnaire about each of them. This will enable you to get specific and consistent insights about each snippet.

- Post-study interview. After the study, evaluate all the information provided by each participant. Plan a follow-up interview to discuss logs in detail. Ask probing questions to uncover specific details needed to complete the story and clarify as needed. Ask for feedback from the participant about their experience participating in the study, so you can adjust your processes for the next time.

- Data Analysis. Because diary studies are longitudinal, they generate a large amount of qualitative data. Revisit your research questions, then take a deep breath and dig into all of the rich insights you’ve collected to find the answers. Evaluate the behaviors you’ve targeted throughout the study. How do they evolve and change over time? What influences these behaviors? If the focus of your study is around a particular product or service relationship, look at the entire customer journey. Construct a customer journey map to help you understand the end-to-end user experience from the perspective of your customers.

Motivating participants

Getting the insights you need will take some involvement with participants throughout the study. Plan to check in with participants or give periodic reminders as needed (each day or every few days). For participants that are engaged and creating appropriate snippets, recognize their efforts and ask them to keep up the good work. For participants that are less engaged, give encouragement or offer to answer any questions they may have to get them on track. Let participants know up front that you will be reaching out throughout the study and agree on a means of contacting them, so you can give encouragement or ask for clarification without being overly intrusive.

Diary studies require time and dedication from participants. To ensure you get the level of involvement you need from participants, provide an incentive that will keep them engaged. This compensation is typically much more than what you would offer for a 60-minute usability test. Align the incentive with the amount of work required over the period of the study. Consider breaking apart the total incentive and offering smaller installments as participants reach specific milestones (e.g., 3 days of logging), to keep them motivated throughout the duration of the study.

In a recent diary study with college-educated participants from various different regions across the United States, we paid each participant $275. Users had to complete a pre-assignment to install software on several personal devices before the logging period, log snippets for 2 weeks, fill out a web-form questionnaire for each snippet, and participate in two phone calls (a pre-study brief and post-study interview). The incentive was dispersed in 3 phases as users reached specific milestones throughout the study, to keep participants engaged throughout. This study had a completion rate of 90%.

More Tips for Diary Studies

- Plan for an appropriate reporting period. Make sure your study is long enough to gather the information you need, but be cautious about designing a very lengthy study. If your study is too long, participants may become less engaged as the study progresses, which could result in less accurate data.

- Recruit dedicated users. Since diary studies require more involvement over a longer period of time, be extra prudent in the recruiting process. Let users know what is involved and expected of them up front. Ask screening questions that will help you gauge the level of commitment you will get from them during the study, and be sure to confirm they will be available for the entire study period.

- Be on top of the data as it comes in. If you are getting data digitally or immediately as it comes in, evaluate it right away. This allows you to ask follow-up questions and prompt for additional detail as necessary, while the activity is still fresh in the minds of the participants

- Conduct a pilot study. Diary studies can take quite a bit of time to plan and conduct, so it’s helpful to conduct a short pilot study first. The pilot study does not need to be as long as the real study and it is not meant to garner data for analysis. Its purpose is to test your study design and related materials. Practice the process of briefing and debriefing pilot participants. Try out your logging materials to be sure they’re understandable. Tweak your instructions and approach to ensure you get the data you need. Ask pilot participants for feedback about materials and the diary study experience, and adjust accordingly.

Conclusion

While diary studies can require more time and effort to conduct than other user-research methods, they yield invaluable information about customers’ real-time real-life behaviors and experiences. If you’re looking for organic behavioral insights and you can’t create a valid scenario in the lab or you can’t get the data you need from a single survey, don’t force-fit the research into these methodologies. Diary studies allow you to get a contextual understanding of users’ behavior and experiences over time.

Share this article: