We often focus too much on current events: what’s happening this year in our industry. Or what’s happening this week on our project. Sometimes current events in UX are positive. Other times we’re frustrated that “obvious” UX improvements aren’t made and bad designs are imposed on a suffering customer base.

In the short term, there will always be ups and downs, but let’s take the long view for once and consider a hundred years of user experience, from the early days in 1950 to the likely future state of the field in 2050. This 100-year view is positive beyond belief.

The Dawn of UX

In 1993 Don Norman coined the term “user experience” for his group at Apple Computer. (Watch Don explain the history of “UX” and what he thinks of how people use his word now.) But the field is older than the term.

It’s hard to draw the line between traditional human factors and what we might call ‘user-experience’, aimed at human-centered design of interactive systems. Bell Labs was one of the pioneers in making this transition, starting with the first psychologist hired to design telephone systems in 1945: John E. Karlin. By the 1950s, Bell Labs definitely did UX work, in particular on the design of the touchtone keypad. That we use its design to this day is proof of how important it is to get the UX right in the first place. (Update 2021: in research for my keynote UX 2050, I derived the estimate that the touchtone telephone key layout has been used to place about 40 trillion calls since it was designed by that early UX team.)

In 1990, I started a new job in one of the departments at Bell Communications Research that had grown out of this early effort. By then, there were several places doing great UX work, but I chose the Bell Labs spinoff because of my assessment that this group was the #1 in the world. Again, showing the benefits of getting an early start.

100 Years of Growth for the UX Profession

UX has come a long way since 1950. It has even come a long way since 1990. But I still feel that the overall quality of user experience — whether on the web or for computers in general — is less than 10% of what it should be. Much too complicated for average people. We need to go a good deal further.

To operationalize the question of “progress of the UX field,” I’ve chosen a single variable: the number of user-experience professionals in the world. Obviously, I can only give you my best estimate, since there’s no agreement on what constitutes a “UX specialist.” (In our research on UX careers, we found that 1,045 UX people held 210 different job titles.)

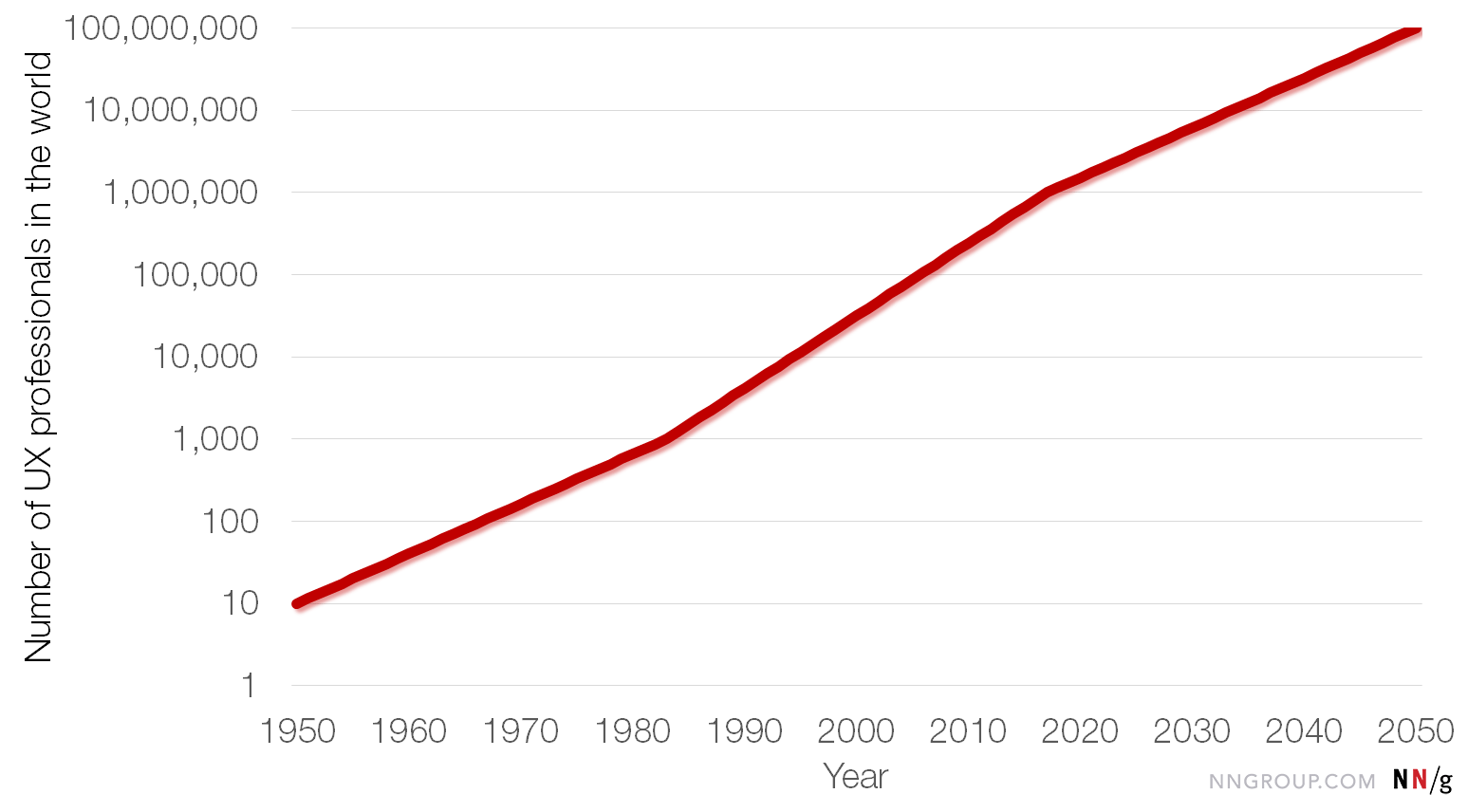

The following chart shows the estimated number of UX professionals from 1950 to 2050, with future years being a projection:

3 Growth Rates

Eagle-eyed readers will have spotted that the line in the above chart has different slopes in the beginning, middle, and end. On a logarithmic-scale chart, straight lines represent exponential functions, and the slope of the line shows the growth rate. Basically, I’m saying that the growth rates were somewhat different during each third of the 100-year period:

- 1950 to 1983: the UX profession grew from about 10 people (mainly those early Bell Labs guys) to about 1,000 people. A growth factor of 100.

- 1983 to 2017: the UX profession grew from about 1,000 people to about 1 million people. A growth factor of 1,000. (LinkedIn had 1.5 million members in late 2017 who claimed expertise in user experience, usability, or information architecture. Claiming a skill and actually having it are two separate things, but then many people are not on LinkedIn, especially internationally, so the estimate of 1M UXers is not far off.)

- 2017 to 2050: the UX profession is expected to grow from the current about 1 million people to about 100 million people. A growth factor of 100.

I started in UX in 1983, so that middle third of the 100-year period coincides with my career. There are a few reasons why UX grew extra fast during this period:

- The PC revolution of the 1980s put extra pressure on the computer industry to improve the usability of its products. Before personal computing, there had definitely been a need for usability, which is why UX personnel grew by a factor of 100 during the mainframe era. But mainframes were enterprise computers, meaning that those who used the computer were not the ones making the purchase decision. So, during that early era, the computer industry had had little incentive to produce high-quality user interfaces. With personal computers, the user and the buyer were the same, so the user experience directly impacted purchase decisions. Also, an extensive trade press published reviews of all new software products, often discussing their ease of use. (PC Magazine had a usability lab by 1991 and the usability score counted for 1/3 of the overall review rating of a software product, with performance and features counting for the other 2/3.)

- The web revolution of the 1990s and 2000s put further pressure on companies to improve the quality of their interaction design. With traditional PC software, the sequence of payment and user experience had been as follows:

- You bought a box of shrink-wrapped software.

- You opened the box, installed the software, and only then did you discover that it’s difficult to use.

- You go to the company’s homepage. If it makes sense, you navigate the site. If you can find your way, you finally get to the page for a product you may be interested in. If the information on the product pages seems relevant to you, then you may proceed to the next step.

- You click Add to cart, move through the checkout process, and finally give the company your money.

- The great press coverage of usability made UX the “hot new thing” (although it was already 50 years old by 2000, so not really that new). Especially during the dot-com bubble, I personally remember doing more than a thousand press interviews, often with the world’s leading newspapers. (See some of the most interesting UX cover stories.) This strong positive PR for UX made many companies think “we need some of that.”

These 3 factors (PC revolution, web revolution, press coverage) put extra oomph in the growth rate for UX during the middle third of the 100-year period I’m analyzing. Going forward, it would not be realistic to assume as high a growth rate, so my hypothesis is that, during the next 33 years, we will revert to the growth rate of the field’s first 33 years.

Experiencing the Growth of User Experience

You may think that you don’t see the rapid UX growth that I have outlined above. That’s because the growth is driven by 3 factors, only one of which you personally experience:

- More UX staff within your company. This is the one aspect you can witness directly. Most companies gradually increase their level of UX maturity and hire more UX people, as management recognizes that proper UX methodology substantially improves product quality.

- More companies doing UX. You won’t directly experience this factor, unless you pay close attention to the #UXjobs feed. But more and more companies start UX groups and hire UX staff. There are constantly more companies reaching UX maturity level 4 (Structured), and they have to also hire UX managers. I can attest to strongly increased demand for UX management courses, driven by the large number of new UX groups in companies that didn’t use to have them. In the early days of my career (when there were about 1,000 UX professionals in the world), UX was basically found only in the IT industry. Now, every field of business needs UX, because brand is experience in the modern world.

- More countries doing UX. When I was young, UX was concentrated in the US, UK, and Scandinavia, with a few outposts in Australia, Canada, and Germany. No more. UX is now worldwide. Some of the best experience architecture innovations are happening in China (and I’m blown away by the talents of the Chinese interns I hired for our next round of China-related research). The UX Conference had attendees from 74 different countries this year, whereas only 69 countries attended last year. An increase of 5 countries in a single year.

We have to multiply these 3 growth factors together to arrive at the worldwide growth of the UX field. Yet, unless you’re from, say, Kazakhstan, you wouldn’t know that that country sent its first representatives to the UX Conference this year. And you probably also don’t know that the investment in UX in Indonesia has increased by an estimated factor of 10 in just the last two years. Thus, most of the world’s UX growth isn’t immediately visible to any individual UX practitioner.

Modest Past, Strong Future

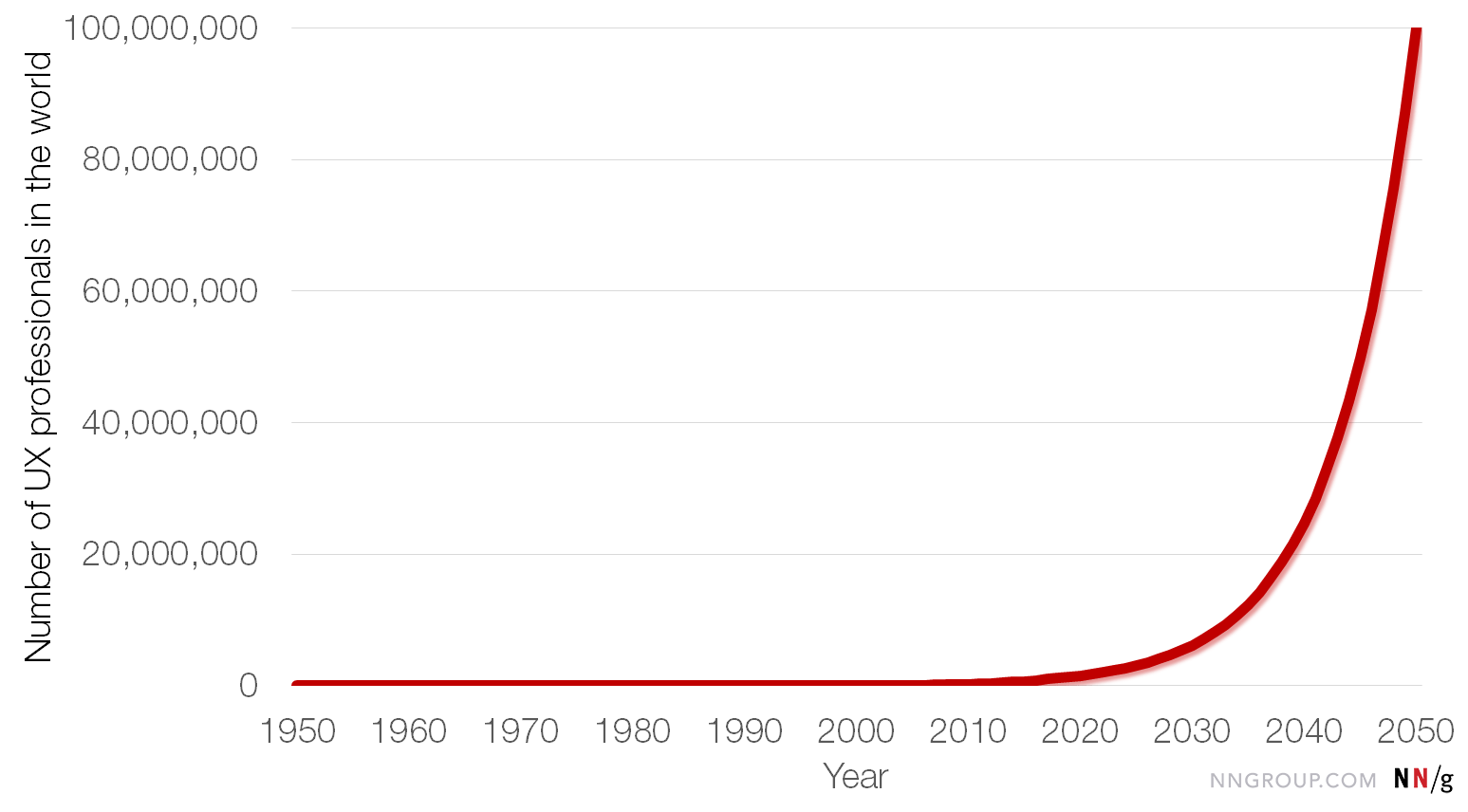

The above chart shows the growth of the UX field on a logarithmic scale, because that’s the only way to properly visualize the changes during a 100-year period. However, we don’t live in a logarithmic world, we live in a linear world. So the following chart shows the same data on a linear scale:

On the linear scale, we see that the entire history of user experience is nothing compared with the likely future of the field. The line hugs the x-axis so closely that we can’t tell the difference between the birth of the field and the present day. Around the year 2020, the curve will finally start bending, and the subsequent years will be a true rocket ride. For all practical purposes, the growth in UX is still to come.

I’m predicting that we’ll be 100 million UX professionals in the world by 2050. This corresponds to 1% of the world’s population.

Is it realistic to expect that an entire percent of the population will be occupied with something as esoteric as user experience? Yes, because UX won’t be esoteric in 2050. It will be a key driver of the world economy. I think it’s completely realistic to expect 1% of the population to work on figuring out what should be designed, and then designing those products (and services). The remaining 99% of the people can then work on building, selling, and servicing what we have designed.

The main value driver in the future economy will be user experience. Not only will UX be a key differentiator between premium-priced products and commodities, but it will also be the only way to overcome the productivity languor that’s currently plaguing advanced countries.

When most value is produced by knowledge workers, the way to increase productivity is to employ cognitive-design strategies and create products that augment the human mind. Technologies that negate human skills are a prescription for continued low productivity in the knowledge economy.

We know that UX generates strong ROI, and will continue to do so as we turn to solving the advanced economies’ productivity problems, expanding the goal of the UX profession beyond the current obsession with addicting users to their social media feeds.

It will totally pay for itself many times over to have 1% of the world’s population become UX professionals. The other 99% will thank us as they will finally master technology instead of being oppressed by it. And even if they don’t realize that a substantial proportion of the growth in the world economy will be to our credit, they’ll still appreciate how much richer they will be because of us.

If you can’t tell by now, I’m very bullish on the future of the UX profession. What we’ve seen so far is nothing compared with what’s to come.

Share this article: