Google Drive, Dropbox, OneDrive, iCloud — these have all become common household names. They are all cloud-storage systems that people use them every day for a variety of purposes, ranging from syncing information across devices to collaborating in real time with others.

Yet, these systems are complex and users don’t always have a good understanding of how they work. To get a sense of how people think about these systems, we interviewed 8 participants who shared their practices related to their use of Google Drive, OneDrive, and Dropbox. Some also briefly described their experiences with other services such as Apple’s iCloud and the Adobe’s Creative Cloud.

Complex Systems, Simplified Mental Models

From a user perspective, in a normal interaction with a website or an application, there is normally a single agent force: the user. Changes in the state of the system occur usually in response to a user action, and users can build a fairly simple mental model based on the alteration between executing an action and evaluating the system response — at least, if the design follows usability heuristic #1: visibility of system status, so that users know what the system did.

Cloud-based systems are different in that multiple users can interact with the system at the same time; these interactions can all change the state of the system. (Furthermore, the system may have AI agents that cause additional changes without the action of any humans. Sure, traditional, noncloud systems can have this feature as well, but it’s more common in the cloud.) Because of that, it can be difficult for users to understand the state of the system at a given moment or predict the system’s reactions to any particular action.

Our research indicates that users try to adapt to the multiagent paradigm in rudimentary ways:

- They use external, traditional channels (such as email or in-person communication) to share information and set rules of collaboration.

- They are mindful of other people’s contributions and overcautious when it comes to modifying or deleting data that may be shared with others or by others.

- They poorly manage their information because of (1) a lack of understanding of how moving it or deleting it modifies access rights and thus affects others, and (2) the UI limitations of a web-based interface (in which direct manipulation is supported to a lesser extent than customary in other similar types of interfaces).

- Privacy is rarely an issue: at least with systems from established companies like Google and Microsoft, people are willing to ignore it for the sake of convenience.

- (Re)finding information shared by others is challenging and involves using external tools such as email. This issue is complicated by the fact that some of the shared information lives in multiple places.

Note in this list the heavy reliance on traditional, single-agency mechanisms to bypass the complex cloud systems: email, in-person communication, real-world brand trust.

Poor information management leads to a proliferation of old information, with little understanding of who can access it and in what way (view versus edit). Because people have trouble checking permissions, often information that is confidential continues to stay shared with individuals who no longer should have access to it (for example, because they don’t work for the organization anymore).

In many ways, users seem to try to fit these multiagent systems into existent, simpler mental models that they had for similar single-agent interactions. An example is the permission-clash problem, which arose when people attached documents from the cloud to an email without realizing that these documents needed the right permissions in order to be accessed by the recipients. Thus, they transferred the existing email-attachment mental model (which says that the document is sent to the email recipient) to “attaching” cloud documents.

While we document these issues for the use case of cloud-storage services, it’s likely that they will be encountered in a variety of other similar cloud services where multiple users can change the state of the system.

Why People Use Cloud Storage

There were several main reasons that participants in our study reported for using these systems, listed below in the order of their frequency:

- Sharing information with others

- Access to documents from everywhere

- Transferring and syncing information across devices

- Collaborating on documents and other files with others

- Extended storage and backup or file archival

Google Drive and OneDrive were used the most for collaboration — because of their respective connection with Google Docs/Google Sheets and Microsoft Office 365, respectively. Dropbox also has an application called Paper that allows document cocreation and collaboration, but none of our users were familiar with it.

The choice of one particular service versus another was usually dictated by circumstantial factors:

- Integration with other services. Many users reported already being immersed in the Google or Microsoft universe, so using the cloud-storage service came as a natural extension of their practices (in the same way in which, for example, QR-code scanning became common in China because it was embedded in the highly popular WeChat service).

One participant described why she started using OneDrive: “We were already a part of the ecosystem, you know, so it just, it made sense since we already use Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and even Outlook at times. […] We also use Skype for meetings, both personal and business.[…] So that made it easy just to say, ‘okay, let's just use OneDrive.’ Because that's a part of the ecosystem and it just makes it easier, more seamless to us to work across the board.”

In the case of Google Drive and OneDrive, people felt it was also easy to access the service through email and other applications that they already were using, and, thus they did not need to log in separately:

Some got to use Google Drive because they had started using Google Docs and Google Sheets for collaboration. Similarly, in the Microsoft universe, several participants recalled starting to use OneDrive because it was integrated with SharePoint or with the Office 365 suite.Some people used iCloud to store photos because it was already linked to their iPhone.

“I use Google Drive because there's Google Sheets and Google Docs. […] There's the ability to collaborate on specific documents that you can share to your drive. I don't know if Dropbox has that same functionality or if you have to work in Excel and then save something. We never did any kind of collaborative stuff […] until we started using Google Drive and Google Sheets.”

- Collaborators and coworkers use it. Many people reported using a system in order to collaborate with a specific group of people that was already using that system. In some cases, their workplace enforced the use of one system (e.g., OneDrive) and the company’s IT department had integrated and installed that software on the users’ computers.

One participant explained: “Basically, every manager on my team has a OneDrive and we set it up for the different entities that we manage. We do financial reporting for different entities, so we use it as a file-storage area, so that also our teams can work in there in […] a collaborative environment, so they can be […] updating things while I'm […] reviewing things.”

Capacity Limitations

While users did not report being worried about storage capacity for Google Drive or OneDrive, Dropbox tended to be used less for file archival or storage, especially because of its capacity limitations: our participants did not want to pay for the service, so they avoided storing too many files on Dropbox. One participant described her strategy to avoid going over the storage limit:

“I actually have a free version of Dropbox and it fills up quite quickly. So I will accept files from a client or someone I'm working with and then, when I'm done with that project, I'll sort of deactivate those so I can make more room for something else.”

(This strategy is not big news: people tend to use a version of it whenever they are in danger of running out of space. For example, in our study of mobile users in India, we found that they often tended to save apps to their SD cards to avoid using their phone’s limited storage capabilities.)

One common issue with Dropbox was that, in order to be able to actively use a shared folder, the user needed to add it to her Dropbox space, thus consuming her own storage. One participant described using the Pending shared folder feature of Dropbox, which essentially allowed the user to keep track of a folder that was shared with her without adding it to her Dropbox. She mentioned waiting to add that folder until she was ready to start working on it.

“I have to get rid of things to [free up space on Dropbox] — for example, this folder, photos for the anniversary book, is now in the Pending shared folders because the project's not done, but I had another project that came in that took up a lot of space, so I had to move that out. So […] I've kind of moved it out of my folder, and when I need to use it again, I'll have to free up some other space and put that back in.”

Another way to circumvent Dropbox’s capacity limits was to use files shared by other people via links without saving them in the user’s own account. This practice was cumbersome, as users had to find the link that was shared with them (usually by searching old emails) every time they wanted to use the file.

Privacy Concerns

People were usually not concerned with the privacy of the information stored in the cloud. Most of them were trusting of the service providers and were willing to share even the most private information such as social-security numbers or tax documents. Especially with Google Drive and OneDrive, part of the reason was that they already had established trust in Google and Microsoft, after using many of their products over time. Also, in some cases, the cloud-service use was enforced by their employer, which added legitimacy.

“I am slightly concerned because some things are quite sensitive and, you know, it wouldn't be good if just anyone could access them, but […] I don't think about it too much.”

Devices and Channels

All our participants reported using Google Drive and OneDrive primarily on their desktop and laptop computers. While most also had the corresponding apps installed on their phones, they tended to use them only for viewing information — several mentioned that editing files on mobile is too complicated (a finding that is in line with our study of device importance).

One user explained: “I have a Google Drive app on my phone, and I will only use it as reference. So, if I'm somewhere, I'm not making edits on my phone, screen's too small and I don't like typing on my phone; I will use it just so I can pull things up and then reference them.”

Dropbox was somewhat different — because it was seen primarily as a way of sharing and transferring files, not so much for storage or collaboration, some people reported using it mostly on the phone, to transfer photos.

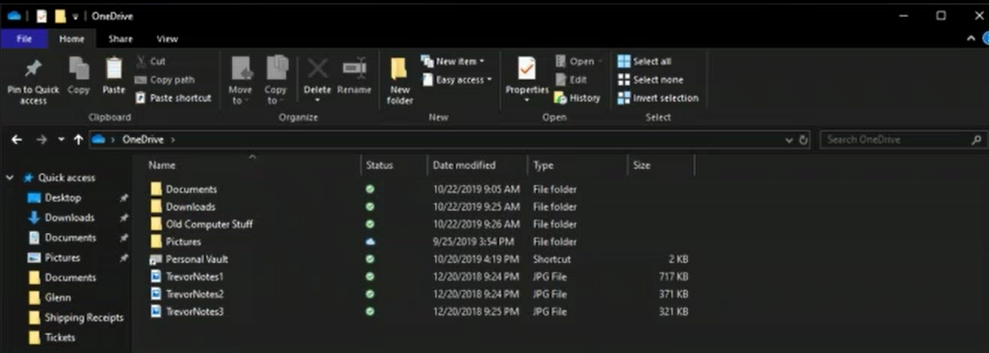

On computers, most of our users (with one exception) accessed the service through the web app as opposed to installing the native desktop app. One participant did use OneDrive only through the desktop app and several had it installed (for example, because their IT department had installed it), but did not make use of it. The use of the web channel influenced many of the views people had about these services.

Interestingly, the person who had the OneDrive native app installed on his computer used it exclusively for file storage and access across devices — he never shared files with others. He effectively treated OneDrive as if it was another storage unit on his computer.

File Organization and Management

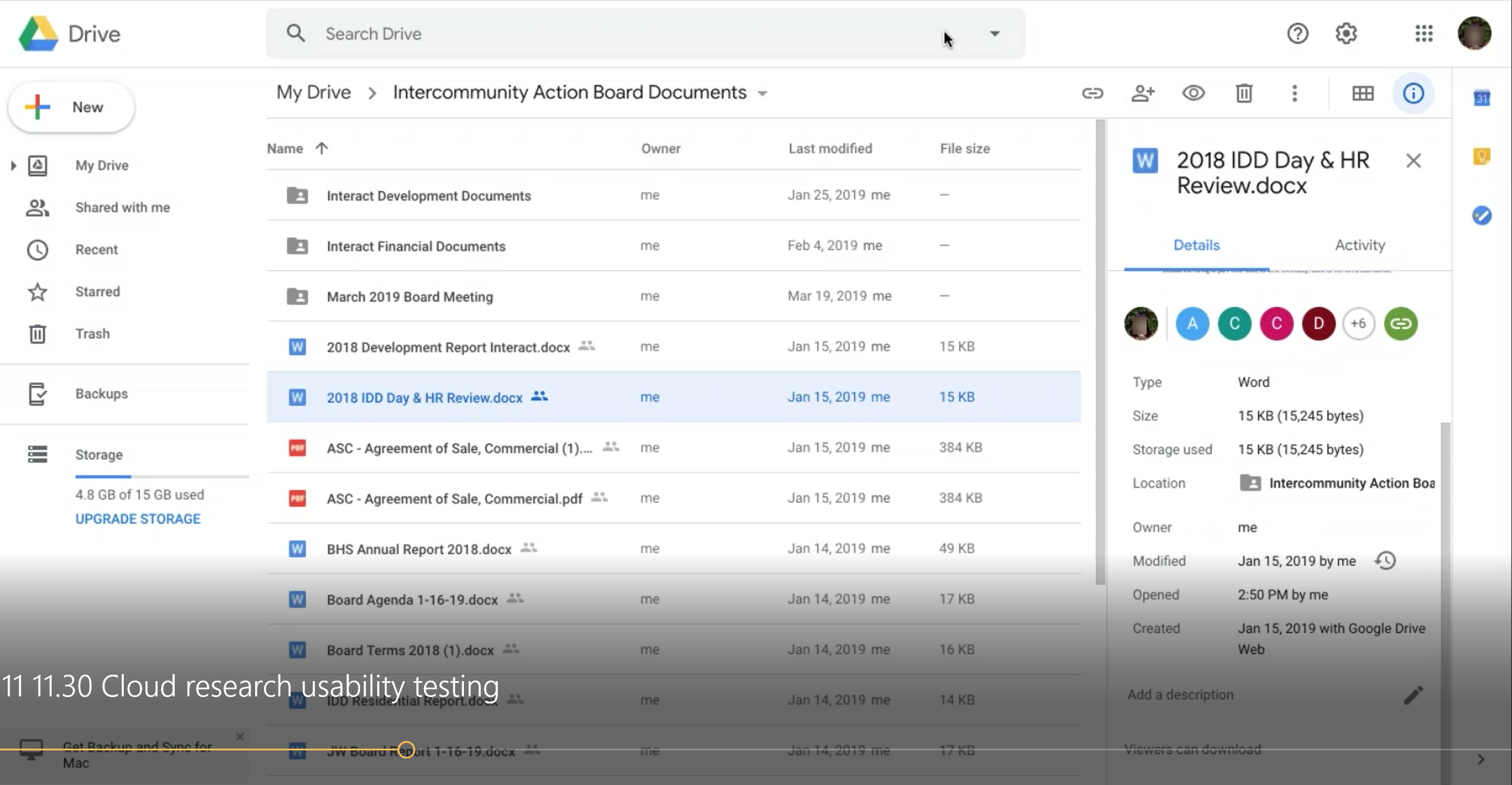

Most of Google Drive users had no clear organization of their files. Some people had created folders to share with specific collaborators, but many of the files were just dumped, with no strategy for information management. To find a file, people reported searching for it, relying on the recent-files feature, or searching through their email to find files shared with them by others.

“The way that I would [find a document] is go through my Gmail because I think there is a corresponding email that comes with that sharing. […] I'll type in kind of my rough memory of that or who I think sent it and then search all the emails from that person.”

A complication was that, with some services, the files shared by others could appear in multiple places — for example, in Google Drive, it could be in the Shared with me space and also wherever in the folder structure the receiver may have put them.

One of the effects of poor information organization was the well-documented out-of-sight, out-of-mind effect: some participants had completely forgotten about the stuff that was in their cloud-storage account — many expressed surprise at the files they found there:

“Oh, I think I used to use that for my business. Oh gosh, that's really old. A lot of this is really old. […] Looks like I have a recipe file, which I clearly have not used. That is, I forgot it's there.”

One user mentioned that she had difficulty organizing her Google Drive files because she could not easily drag-and-drop them or see multiple windows at once:

“I find it to be actually quite difficult to organize things on Google Drive because I'm used to a desktop where you can drag-and-drop things and you can have multiple windows open at once and […] I can see, you know, three or four folders and I can drag things between those folders, which I can't do in Google Drive. So, I often wish I could organize the Google Drive better than I do.”

On OneDrive, users tended to be somewhat more organized with their information. OneDrive’s default UI more closely resembles the traditional file-system interface, so it’s possible that people had a slightly easier time organizing their information. Even though direct manipulation was available at least to some extent across all three services, it seemed less salient on some than on others, and the salience influenced peoples’ information-management practices.

Where Do Files Live

None of our users expected the files stored in the cloud to be available offline or relied on the offline access that the cloud services provided. Even the participant who used OneDrive exclusively through the native desktop app did not realized that copies of (some of) his files were stored on his local hard drive. In fact, he mentioned using the cloud to free up his local storage:

“I know that on the computer there's only a certain amount of space that it can handle. […] I use [OneDrive] as a secondary storage space […], like almost like a digital filing cabinet of sorts. Like if, if there's something […] I may need to access […] later, but probably not — let me, just in case, make sure though that I heap it somewhere. What I'll do is I'll just take it, I'll cut it, go to my OneDrive, my documents […] And then, you know, it's not on my computer, but I have it still like in a digital filing cabinet.”

(OneDrive does have an indicator showing when files are available locally, yet its meaning was not clear to our user.)

And some Google Drive users said that they assumed it would be possible to make Google Drive work offline, but they had never thought about it.

When we asked them how they would access their file offline (e.g., on a plane with no Internet connection), all of our users said that they would take extra steps to download the file from the cloud service and save it as a separate file on their computer. Then, once they were back online, they would simply upload the modified file manually back into the cloud:

“What I'll do beforehand is I'll always take whatever file or folder that I need to access and I'll just drag it over [to my own disk] […] it's like, okay, well, whether I had the internet or not, this is on my actual [computer].”

Who Has Access to the Cloud Files

Most of our users had a very muddy understanding of access rights and how these change as files get copied or moved around. Even checking who had access to a file was difficult for some — the cloud interface did not make it particularly obvious. It was clear that most users did not check permissions very often.

In the words of one participant: “Actually I don't really know how to check [who has access rights to a file] […] I feel like I remember giving someone access to documents before or to editing documents, but I cannot remember how I did it, […] I can't figure it out right now.”

An added complication was that a file could be shared by sending a link to the recipient or by explicitly adding that person to the list of people who could access the file. Sharing by link did not allow users to see who had access to the file. Some preferred to share by link because they felt it was easier (emailing the link to a group of people was simpler than adding that same group to the permission list, perhaps because the emails were already saved in the email client, plus it fit the existent mental model of sharing a webpage). Also, some email clients were integrated with the cloud service and made it easy to attach a cloud-based document (although this practice often led to permission clashes: attaching it did not always allow the recipient to access the document, if the permissions were not right).

A consequence of the low visibility of access rights was loose information security. Several of our participants still had access to work-related content from previous jobs, because the permissions had not been updated when they left. (Even if their account with the company may have been deleted when they changed jobs, some files had been shared through links or with the user’s personal account.)

Access Rights for a New File

When people created a new file in a shared folder, all participants expected that everybody with access to that folder will have access to the file — basically, that the file inherits the access rights of the parent folder.

But this model started becoming muddled as we asked them what would happen if they changed the location of the file or if they deleted it. Most people simply recognized that they did not quite know what would happen and they had never thought about it. This lack of a clear model made them unlikely to want to clean up or reorganize information and partly explained why generally their cloud-storage repositories were relatively messy.

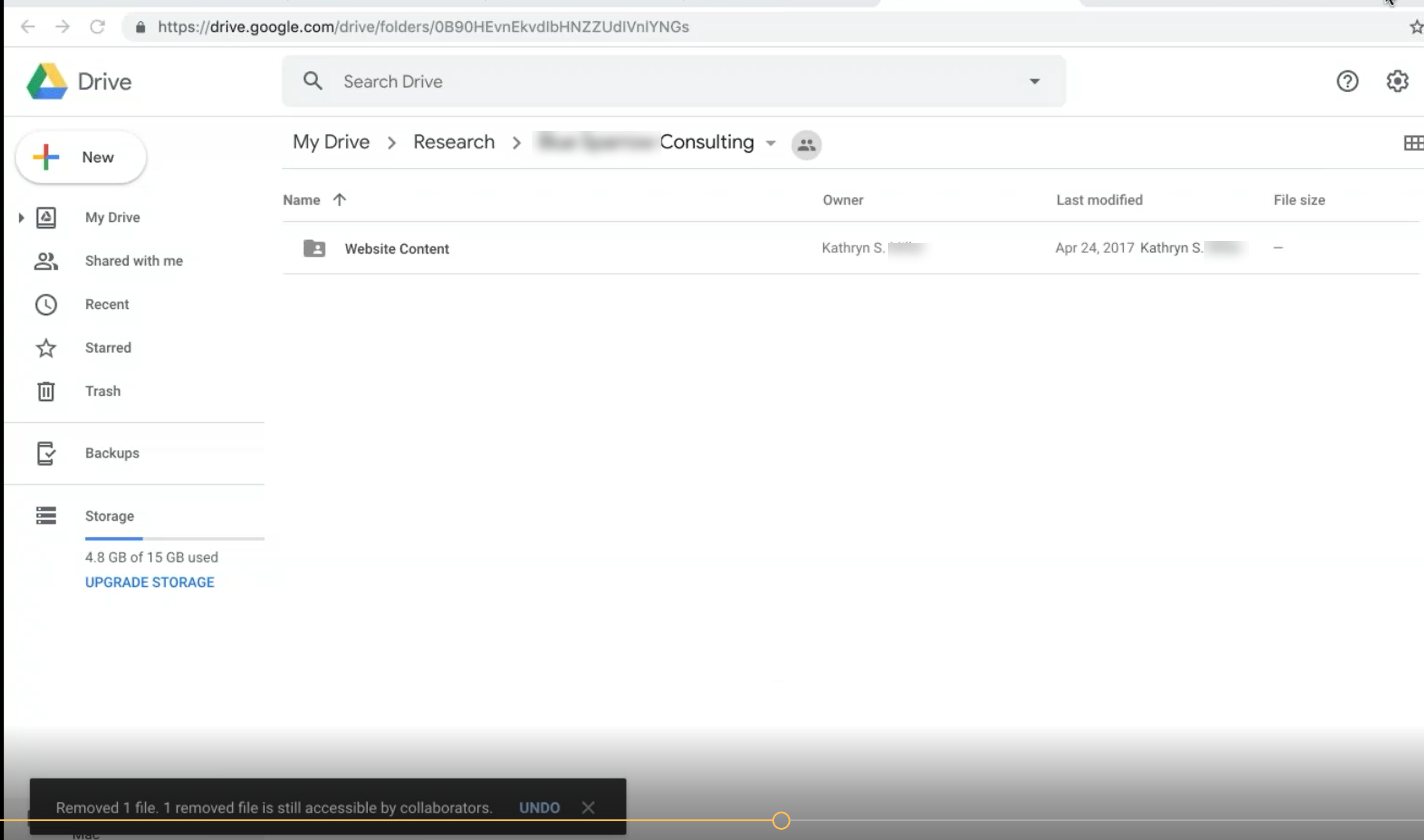

Permission to Delete a File

Participants had vague and inconsistent expectations about what would happen if they tried to delete a file in a shared folder. Some thought that only the owner would be able to delete the file, and others believed that anyone who could edit the file would be able to delete it. One person thought that the file would disappear from her own view but still be accessible to the collaborators.

Moving or Copying a File

People had no idea what would happen if a file would be moved to a different location. When asked, most participants guessed that, when the file was moved from a source to a destination, its final permissions would be a merge of the source and destination permissions. Thus, they felt that if they moved a file shared with person A into a folder shared with person B, then both A and B would have access to that file.

To quote from our participants:

“[If you move the file in a different folder], I don't see why [current collaborators] wouldn't [have access to it] […] even if the [destination folder] was private, that document was still shared initially with all those other people, so they should still be able to have access to it. I've never tried it. So, again, I do not know.”

“So I'm moving from the summer folder in which you don't have permissions to the test folder in which you do have permissions […] I would expect permissions to change. I would expect the people who use admission to still have permission as well if it's moving [...] So basically the permissions will become more inclusive.”

However, that perception was not consistent across situations. For example, if a file shared with person A was moved to a private location (not shared with anybody else), some participants thought that the file would become private and A would lose privileges.

Some people thought that copying a file should retain the access rights of the original, independent of where that copy was put, others felt that the file should be private.

Collaboration Practices

Several of our participants used services such as Office 365 Live and Google Docs or Google Sheets to collaboratively create and edit cloud files with others. We noticed that, generally, people preferred to create their own collaboration policies as opposed to relying on the system-provided mechanisms for collaborative editing or merging. Several participants reported bad experiences with letting the system do the merging when multiple people edited at the same time (for example, some complained that they got an error and could not save the file, so different contributors had to save copies of the files and then merge changes separately):

“Like, I'll hit the physical Save [button] and it'll say that it couldn't update the file for some reason. […] So those instances are very annoying because then you have to reach out to the other person who's in the file and kind of be like ‘you know, changes aren't saving’, so someone has to save a version of the file and then update, based off of what it didn't save.”

Basically, most users said that they try to be mindful of working with others on the same document and usually either agree upon a strategy when they start to coauthor or use practices already established in their work group. They generally avoided working on the same section of the document with another person: “So, I will not click in the same cell as them and try to work on the same thing. And I haven't had them do anything like that either.”

A few practices emerged:

- Divide and conquer. Different coauthors would claim different parts of the document and make sure they only edited those, as described by several participants:

“People will put their names next to […] specific groupings. So, Shawn basically owns these two sections […and] this whole area. There's nobody who owns this one yet, so nobody should be adjusting it even though I think somebody did. […] So, we'll go through this and make our edits to this document. And then we will talk about what was changed, what was added.”

“We kind of have this broken out so that people are working on their specific thing and not bleeding over into somebody else's.”

- Centralized model. Collaborators would comment and make suggestions simultaneously, then a moderator would aggregate changes and commit them.

“Previously when I've collaborated on documents, we might've had, like, six or eight people working in a document and it was often problematic, because people were kind of typing over each other. And the version history gets super messy. One of the reasons we would do that is because we were often working on very last-minute projects. And, so it was like everybody jumped in and put [their] feedback in. And, when that was the case, we would have one person who was, sort of, the moderator of the document and they would be responsible for closing the document at a certain time and then going through and seeing what everybody's comments were and accepting or deleting those comments as it were.”

- Color coding. In this version of the centralized model, different people would use different colors for their contributions and a document admin would take a final pass to commit all the changes and the change formatting.

- Time share. One individual would claim exclusive access to the file for a period of time and worked on it (sometimes offline), then uploaded the changes.

“Some editors that I work with prefer to edit in Microsoft Word, so they will take a Google doc down and edit in Microsoft Word. And I think sometimes people don't like other people to be able to see as they're working on a document. […] People would download it and work on it and then just put it back on back up for people to see the final results.”

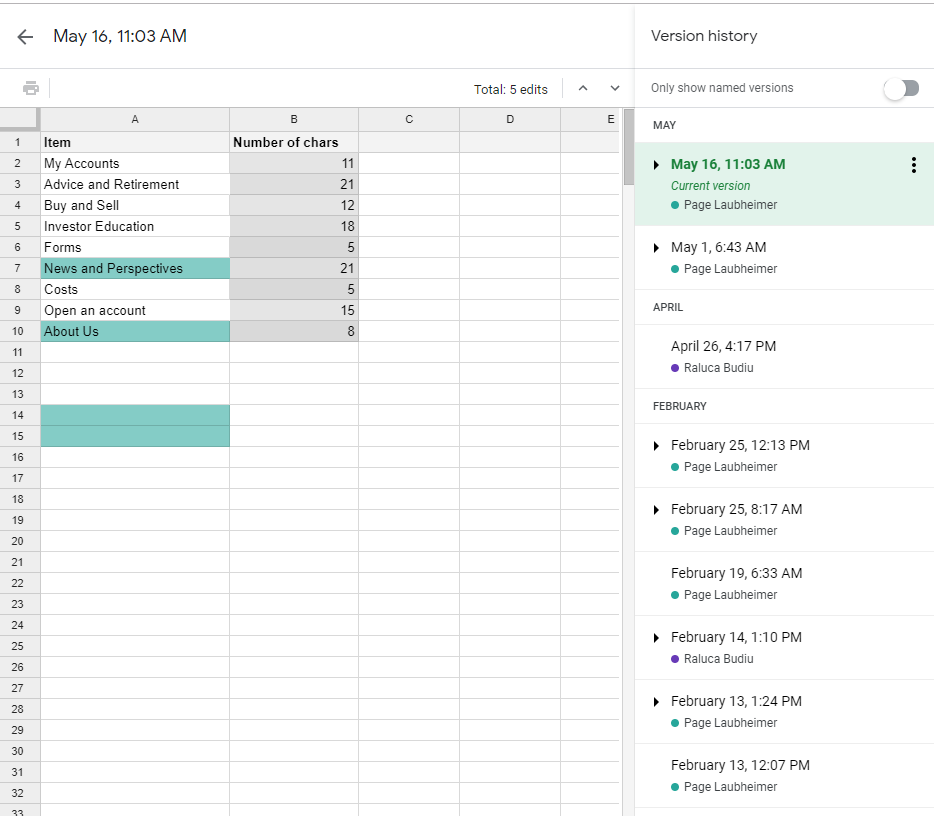

Both Google Docs/Sheets and Microsoft Office 365 make it easy to see if someone else is editing the document at the same time, so users reported taking advantage of those features. They also said they liked seeing the cursor of the other person. One person mentioned taking advantage of the document-related chat functionality.

Accessing the edit history was a valuable feature, but not always easily accessible. Some people complained that the feature was not readily available in OneDrive. And even in Google Drive, where many of our participants praised how easy it was to access the version history, people were not completely sure how to find out what specific changes were made.

“Version history. So these are all the versions and I can see who's made comments to them. I thought there was a way to see who's made adjustments to specific cells, but I don't remember how to do that. […] So in this instance, on September 17, David has adjusted this cell called hazards. I can't see what he's done with it, but I thought there was a way to see what has been changed specifically, but maybe, maybe I am incorrect in that. [So if I really wanted to know what he changed], I would ask him.”

Continuity Between Web Apps and Desktop Apps

The Microsoft Office Suite was available both in the browser and locally, as a native app. Many people did not realize they could open a cloud document in the native app and save it back into the cloud. They felt that the desktop app worked on desktop files and the web app was for cloud files. Some participants thought that they had to explicitly download the file in order to edit it with the desktop app, or that, once they opened a file in the native app, they had to upload it again in the cloud.

People were also annoyed that some of the native apps’ features were missing from the web counterparts (e.g., filters feature in Excel).

Conclusion

We found that, even though participants in our study used cloud-storage systems a lot at work and home for a variety of purposes, they had only a rudimentary understanding of how cloud-storage systems worked and rarely took full advantage of their features and capabilities. Most of the participants were primarily using the cloud in order to be able to access their files on all their devices and to share content with others. Some also took advantage of some of these systems’ coauthoring software, but they were cautious about editing simultaneously with others and often created their own work practices in order to avoid synchronization issues.

Many participants’ cloud storage lacked a good organization structure, for at least two reasons: (1) people tended to use the web UI for the cloud services, and these interfaces had limited direct- manipulation capabilities which did not completely follow the traditional folder-based mental model; (2) because people did not fully understand access rights for shared files, they often were reluctant to reorganize files that were shared with or by others or even thought it was not possible to do it. People also had a hard time finding files shared with them by others and often did an email search in order to retrieve links that others had sent them.

Collaboration was a prized feature, but also involved extra effort to make sure that changes were not lost. People had to establish time-costly strategies (often involving an extra person to moderate the output or in-person meetings to agree upon the final outcome) because versioning was not easy or fully transparent. Even though some people took advantage of the in-document chat features of these systems, a lot of the time collaboration strategies involved external exchanges (through email or in person).

These findings have two classes of implications for two different groups of readers:

- Designers of cloud-storage systems should go to greater lengths to make their capabilities transparent to users. Tips related to offline functioning, more extensive use of direct manipulation, display of file-access permissions, and clear feedback about access rights whenever a file is moved or deleted go a long way in making it easier for users to understand the behavior of these systems.

- Organizations that adopt cloud-storage systems internally need to be aware that people have rarely use them to their full capacity. They can help their employees better take advantage of these systems by setting clear policies and guidelines about how to use these systems inside the organization. Installing the software on people’s computers is not enough. (While we hesitate to recommend user training as the solution to usability problems, this might be a case where a little bit of training could go a long way, especially in organizations that can’t improve the design of an outsourced cloud solution.)

Share this article: