The web is all about hyperlinks. But, you may wonder, when presented with a bunch of links, how do users decide which link to click on and which to ignore? The answer is: information scent. Like food scent guides animals to their meals, information scent guides people to those webpages that are likely to contain the content they’re looking for.

Information scent is a central concept in the information-foraging theory — a theory essential for understanding how people navigate on the web and how they interact with different potential sources of information in order to satisfy a question or an information need. In simple terms, it says that, if people have a question, they will decide which webpage to go to based on their estimate of (1) how likely it is that the page will provide an answer to their question, and (2) how long it’s going to take to get the answer if they go to that page.

The estimate of how relevant the page will be, if visited, is the information scent of that page.

Definition: The information scent of a source of information (such as a webpage) relative to an information need represents the user’s imperfect estimate of the value that the source will deliver to the user, derived from a representation of the source.

Information scent is a relative concept — meaning that the same source of information may have different information scents for different information needs. For example, a link titled Food will have high information scent if you’re looking for cheese, but low information scent if you’re looking for a facial cleanser.

You may wonder what the source of information stands for and what its representation might be. On the web, the source is usually a webpage — most often represented by a link. As the user considers whether to click on that link, the link label, the content that accompanies the link, the context in which the link appears, and any background knowledge (including recommendations from others) that the user may have about the source all influence the information scent that that source emits and thus the likelihood that the page will be visited or ignored.

In our analogy with food foraging, the source would be a food patch— let’s say a savannah. And the representation of that savannah would be what the animal actually sees or feels — for example, the sight or scent of antelopes. The predator (like the human) will likely consider other factors such as any prior bad experiences with that savannah (e.g., the memory of a difficult hunt or of fighting for the prey with other predators) before proceeding with the hunt. And even if it does proceed, the hunt may still prove unsuccessful despite all the enticing cues.

Thus, there are four concepts in play: there’s the actual source (the webpage or the savannah) and its remote representation (the link or the sight and smell of the prey). These have a true value (unknown until after consumption, whether reading the page or eating the food) and an estimated value (assessed before consumption and used to decide whether to proceed with clicking or hunting).

Let’s explore each of the factors that make up information scent.

What Makes Up Information Scent

We’ve seen before that there are two big components of information scent: what the user sees (which is given by the representation of the information source on other pages) and what the user already knows about the source. The first component is largely controllable by designers: we usually can decide how a page will be represented on another pages (although maybe to a lesser extent if the other page is a search-engine-results page). The second component is only indirectly controllable by designers, through the perceived value that they may have constructed in the past for that brand or source of information.

What the User Sees

The Link Label

Perhaps the most important component of the information scent, the link label is supposed to be a succinct yet accurate description of what the page is about. If this description feels relevant to the user’s goal, the link will have high information scent for that user and her task, and she will be likely to click it.

That is the main reason for which we repeatedly argued that link names should be clear and self-explanatory.If the link name is too obscure and vague, people might miss a good source of information. Even if the link label is precise and accurately describes the webpage it points to, it may still miss the mark and have low information scent if it contains words that are not easily understood by the target audience. Jargon, branded terms, or simply too sophisticated words may end up ignored and may not provide enough understandable cues for all your users.

Note. In UX we often use the phrase “a label (such as More or Learn more) has low information scent.” What we mean by it is simply that, whatever your information need may be, it’s hard to guess what the link may lead to. We also sometimes say that “a label (such as News) has high information scent” when it accurately and comprehensively describes what it leads to. Technically, the second usage is incorrect — the label will only have high information scent for those users who are looking for news, but low information scent for people who search for something else. However, even for those people with a different information need, a good label description is useful and valuable because it saves them the effort and disappointment of clicking on a page only to find out that it’s not what they need.

Content that Accompanies the Link

Often, next to a link there may be a short text snippet or a thumbnail intended to present the user with additional information. Even though users may not read all the text associated with a link, they may still scan it and glean additional cues from it. Those cues will augment the information scent of that link.

This fact has two big implications:

- Summary text for an article or page should convey the gist of that information source and add detail to the link label.

A poor summary is a wasted opportunity for the site and wasted time for the user: the site misses the chance to tell the user whether the article will be relevant. As you can see in the Cisco example above, the summary of the headline adds nothing to the obscure terms in the title.

- The image associated with a link should always be descriptive and representative for the page content or for the category it stands for.

Too often sites choose generic images that are only loosely related to the content of the page.

Sutterhealth.org: The images associated with Find Walk-in Care and Find Urgent Care are generic, purely decorative, and don’t add any extra cues to the label. The summary text under these links, however, does explain the difference between walk-in care and urgent care (and shows the keywords in blue). But even choosing a related image is not always good enough — especially if the image stands for a category of objects. The academic literature on categorization (going back to Eleanor Rosch’s studies in the 1970s) shows that not all members of a category are created equal. Thus, people take longer to interpret images of chickens as birds than images of robins because chickens are less representative of the “bird” category than robins. So, when choosing images for your categories, don’t use aesthetics or convenience as your only criteria. Think of a category member that truly illustrates the set of objects that it’s supposed to stand for.

Costco.com: The image chosen to stand for the category Coffee & Sweeteners is hardly representative of what most people think of when they think of coffee. Thus, for a user searching for that category, the image adds little information scent (unless the user happens to be looking for the exact product shown in the image).

Context in Which the Link Appears

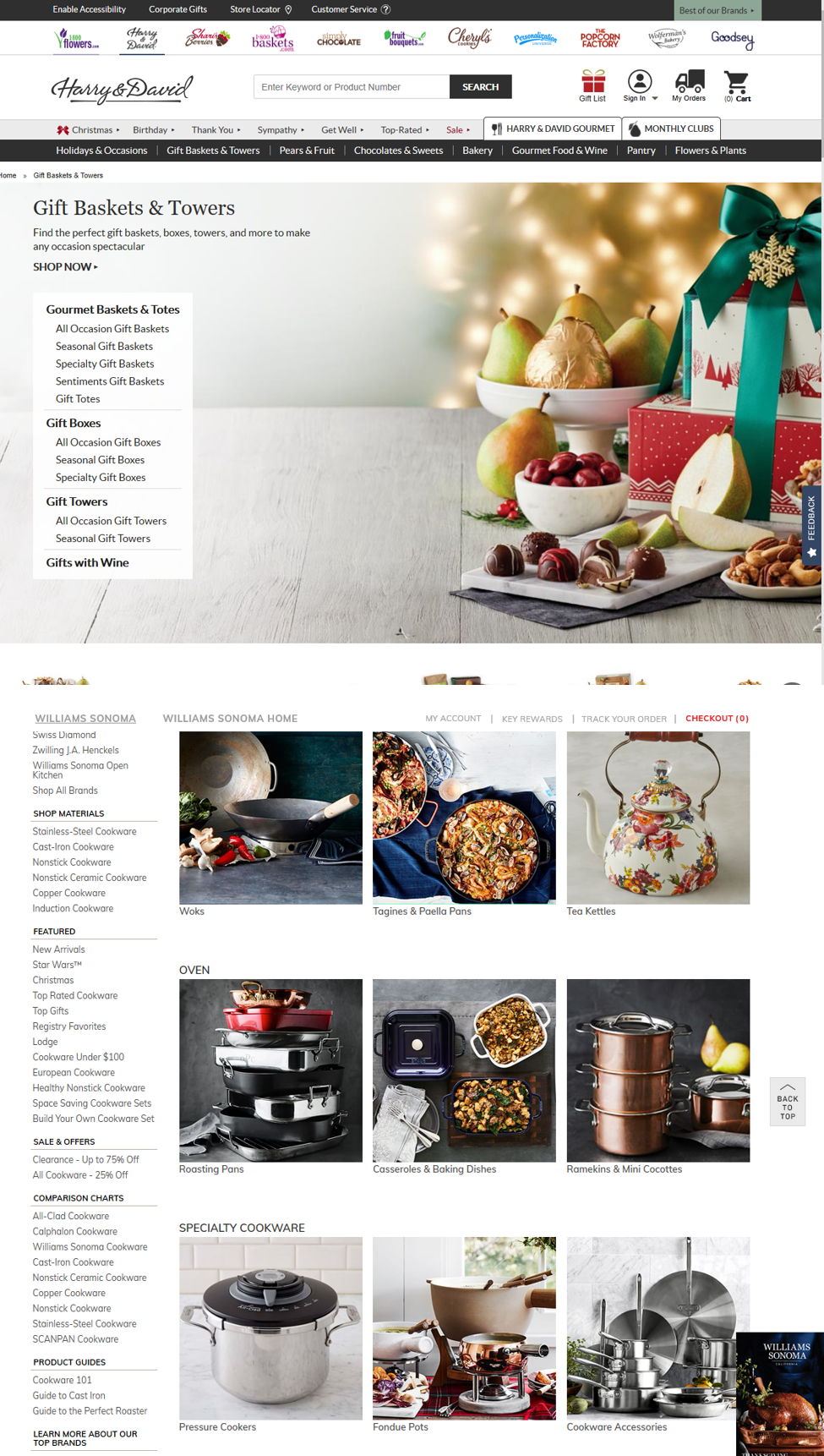

Often, what else is on the page will also influence how a link is perceived (or if it seen at all). For example, for the same information need, the word “Christmas” might have different information scent on two different websites such as HarryandDavid.com and Williams-Sonoma.com. Even if you’ve never heard of the sites before, if you’re looking for Christmas table settings, the scent will be high on Williams Sonoma’s site because of the other related content also visible on the page, but it will be low on Harry&David’s site for the same reason.

Although context is usually a strong cue, designers often make the mistake of relying too much on it. Especially on small screens, the context is not always entirely visible or may get ignored (perhaps because people may scroll quickly past it in search of something relevant). So, it’s always good to be as specific as possible with the link names instead of relying on the context to provide the extra cues.

The other frequent mistake that designers make is not providing sufficient context soon enough. Too often we see landing pages with very little text and a big image on the first screenful. Even when those pages do contain the right information for the user, in many situations they don’t provide enough context to tell people whether they are on the right track. As a result, users don’t bother scrolling anymore in search of the right information, nor do they click on any visible link: they quickly decide that the page is not worth exploring any longer and simply leave. Thus, the good information scent that the link to the site may have provided (for example, on a search-results page) is wasted by the poor context provided by the actual page.

The context can also include the position of an item on the page. Often information presented in the right rail may be interpreted incorrectly as an ad, even though the link description is explanatory enough — simply because people have learned that ads are hosted in the right-hand side of the page, and so whatever information is there will lose in relevance.

What the User Knows: User’s Prior Experience

Another component of information scent is the knowledge that the user has accumulated in the past either directly — over her own previous experiences with the company, with the same type of content, or simply from using the web — or indirectly, from word of mouth or recommendations from friends or strangers.

Here are some elements that are part of the user’s prior knowledge:

Familiarity with the brand and trust in it. If you already know of Williams Sonoma and perhaps have interacted with the brand before, you will be able to understand what “Christmas” on its website stands for even in the absence of other page context. Or, if in the past you have had good experiences with Cisco, you may click on the link to one of its products, even though the link label is not very descriptive.

Familiarity with the domain. If someone is applying to college as an undergraduate, he may know that the common data set (which contains statistics that universities publish about each year’s class of incoming undergraduates — detailing things like range of test scores, GPAs, as well as different admission criteria) is usually in the section of the university site that hosts finance-related information. So, for those people, a link label such as Office of Vice Chancellor of Finance may have high information scent, but for someone who is hearing about the common data set for the first time, that link name may not be at all transparent. (And neither will the name of the “common data set” itself. Thus, a novice user must overcome two levels of poor information scent, making it extraordinarily hard to find the information.)

Social Foraging: Word of Mouth and Recommendations from Others

The social-foraging theory is an extension of information-foraging theory that explains how networks of people collaboratively forage for information. These networks could be organized (e.g., communities of scientist working together on the same problem) or ad hoc (e.g., Wikipedia contributors, reviewers on Amazon, taggers on a collaborative tagging system). The idea is that as people look for information or interact with information, they leave traces for others about the quality of various information source. These traces effectively augment the information scent for other users.

Thus, let’s say you are looking for a hair straightener on Amazon. You choose one and read through the reviews. One extensive review says that this hair straightener is good, but not as good as another one. As you are going back to the page of search results, the information that you now have about the second product will often bias you to click on it and consider it, even if it’s more expensive than the first. That’s because that product carries now additional information scent, offered by the reviewer of the first hair straightener.

Why Click Bait Doesn’t Work in the Long Run

Now that you’ve understood the different components of information scent you may be tempted to game them in order to attract users to your site even though it may not be fully appropriate for their needs. (This approach is often driven by vanity metrics such as number of clicks.)

For example, you may be tempted to come up with an intriguing title that matches a trendy topic for a boring article that is not even remotely connected to the topic. But this approach can backfire. Yes, you will get your click, but at the same time, you will use up your visitors’ trust. Like in the story of the boy who cried ‘wolf’ too many times, next time when you will actually have relevant content, people will be less likely to click on it knowing that they’ve been burned in the past. And even worse, although they may not have been burned personally, they may read complaints from other people who had a bad experience. So you may not even get that first click.

The other side of the coin is that, if your brand is strong and people can trust you, you have slightly more room for error (not a lot — many mistakes will ultimately erode your brand, because brand is experience in interactive media). But basically if you can increase the expectation that users will find what they need on your site and that, whenever you promise something with a label or an image, you will deliver — then people will be more likely to give you the benefit of doubt for the occasional misstep.

Share this article: