Ever had a stakeholder shut down your project or block UX-design efforts? This frustrating situation may be avoided. A significant part of UX involves working with and alongside stakeholders. In particular, in organizations with low UX maturity, UX professionals have to constantly evangelize to stakeholders about their work, why it matters, and why they should be allowed to continue doing it! While we’ve written before that it’s a good idea to collaborate with stakeholders and to invite them to observe research, stakeholder analysis offers a structured approach to stakeholder management.

Stakeholder analysis is particularly useful for UX professionals working on new projects with new stakeholders or for UX teams looking to improve the UX maturity of their organization by increasing the knowledge of (and adoption of) user-centered ways of working.

Who’s a Stakeholder?

A stakeholder is anyone who has interest in your project or with whom you need to work with in some way to complete the project. Your CEO, the marketing director, the account manager, or even your manager could all be stakeholders. Stakeholders can be internal to the organization or external to it. If you’re not sure who your stakeholders are, start by asking yourself who is interested in your project and who has power, influence, or control over it. These questions should lead to a long list of stakeholders.

Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholder analysis involves assessing each stakeholder’s potential to impact your project — negatively and positively! Some of your stakeholders will have more impact than others, and different stakeholder-management strategies need to be applied to those influential stakeholders, compared to those that wield little influence.

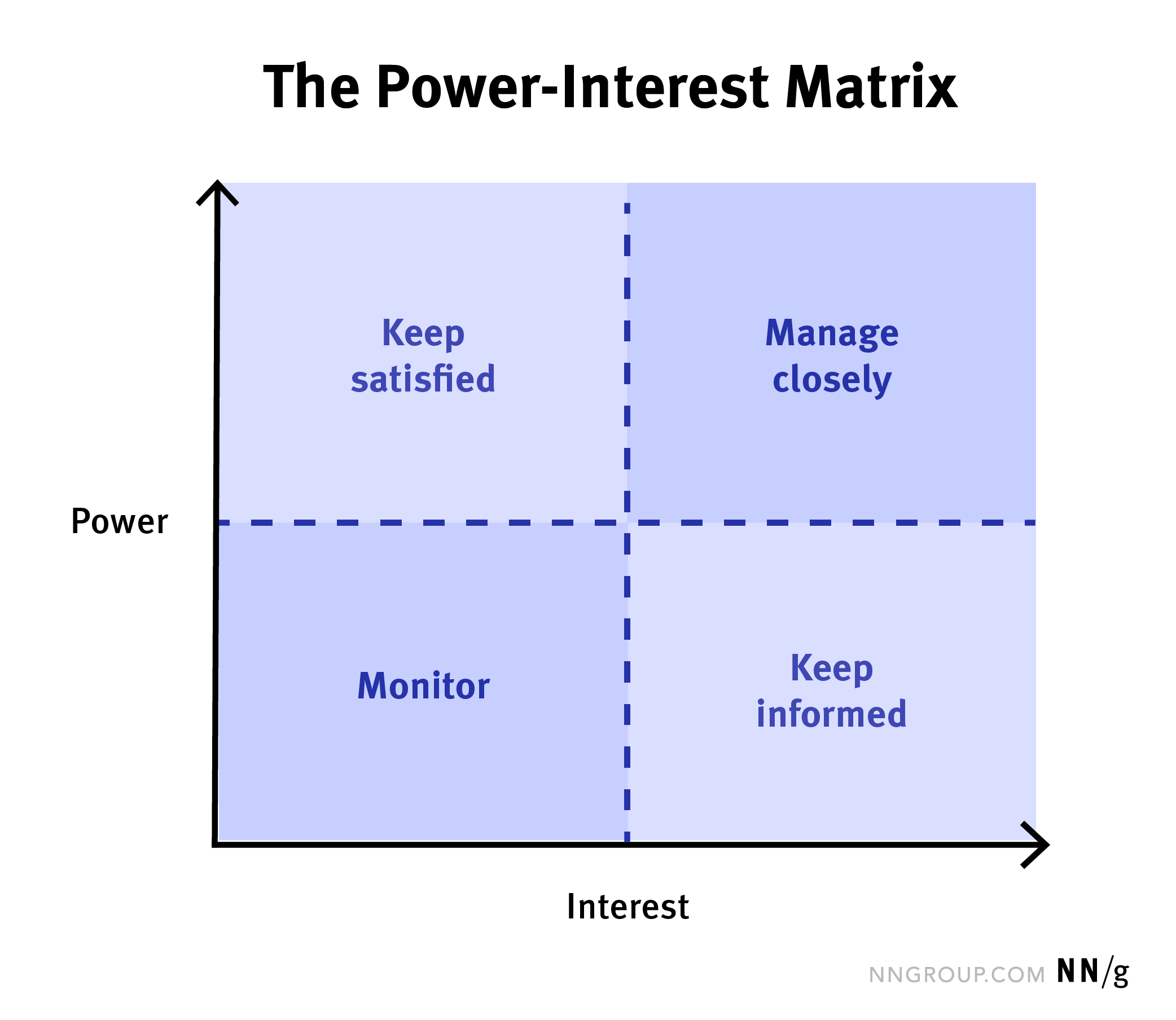

Stakeholder mapping is used to perform a stakeholder analysis. There are many ways you can map stakeholders; one of the most popular mapping methods is the power-interest matrix (often referred to as Mendelow’s Matrix as the earliest version is attributed to the researcher Aubrey Mendelow).

Plotting your stakeholders on the power-interest matrix provides 4 categories of stakeholders and corresponding management strategies.

Manage closely: Stakeholders that fall in the top right quadrant are the most important; they are key stakeholders who are directly interested in your project and exert great influence over the outcome. For example, maybe they make resourcing decisions. Or, your CEO is interested in a redesign and would like to contribute with personal ideas. These stakeholders need to be managed closely; without doing so, they can advertently or inadvertently stop, hinder, or block your project. When managed well, these stakeholders can become promoters of your project, making success a likely outcome.

Keep satisfied: Stakeholders found in the top-left quadrant are referred to as latents; they currently aren’t interested in your project, but they have the power to impact your project greatly. It’s important to ensure these stakeholders are happy. If they find that your work impacts their own, they may get involved. You may want to consult with them to make sure their interests are observed.

Keep informed: Stakeholders who are interested in your project but have little power over it should be kept informed. They should be invited to research, copied into debrief emails, and invited to design critiques.

Monitor: It’s not worth spending a lot of time engaging or managing stakeholders that fall into the bottom left quadrant because they have little interest in your work or power over it. However, circumstances could change, and they could move into one of the other quadrants, and so you should monitor them regularly.

The power and interest that stakeholders have in your project can alter throughout your project. Changes in leadership can result in drastic shifts in outlook and interest in UX initiatives, causing stakeholders to move from one side of the grid to the other. Therefore, stakeholder mapping is not a one-time activity; return to stakeholder maps frequently and update your strategies accordingly.

Notice that the stakeholder-management strategies listed in the grid aren’t specific. The best strategy will depend on the stakeholder and on the corporate culture in your organization. This is why it’s important to carry out stakeholder interviews to figure out what communication and engagement strategies will be most effective. Understanding what your stakeholders care about and what interests them will help you best to communicate with them. In addition, interviews with stakeholders may reveal the extent of their knowledge of UX. If a stakeholder has little knowledge or exposure to UX (and high power or high interest) then you may need to spend extra time to communicate basic UX concepts or explain the ROI of UX work.

One component that is missing in the power and interest matrix is attitude. This aspect is important to understand, so you can prioritize your time and energy. Preaching to the choir isn’t going to ensure long-term success; however, converting a UX sceptic with a lot of power can help you make inroads and garner further support. If you don’t know a stakeholder’s attitude to your work or project, then a stakeholder interview may be needed. You can map your stakeholders’ attitudes as simply positive, negative, or neutral, or label each stakeholder with ‘champion’, ‘supporter’, ‘critic’, and so on.

To capture attitude, you can include a ‘+’ or ‘-‘ by each stakeholder in the matrix to signify whether their attitude to your project is either positive or negative. If you have key stakeholders who are negative, then these are the stakeholders you should spend the most energy on converting.

Alternatively, use a table to list power and interest alongside attitude. You can create a column for current attitude and desired attitude to highlight the gap and where opportunities lie in improving stakeholder relationships. (Note that not everyone needs to become a promoter of your project; some people with low power and interest can be neutral.)

| Stakeholder | Power | Interest | Current attitude | Desired attitude |

| Jane Smith, account manager | High | Low | Neutral | Positive |

| Joe Bloggs, product manager | High | High | Positive | Positive |

| Javinder Singh, tech architect | Low | Low | Negative | Neutral |

Once you’ve performed your stakeholder analysis, the next step is to form a communication (or management) plan. This plan details what strategy you will take with each stakeholder; for example, will you have weekly one-on-one meetings, or will you just send them a quick email every other week? Creating a communication plan ensures your strategies are not forgotten and can be monitored. You can assess if your strategy is effective and improve it going forward.

Summary

Stakeholder management starts with stakeholder analysis — the careful consideration of who your stakeholders are and how much impact they have on your project. Map your stakeholders to understand what power, interest, and attitude your stakeholders have to your work. Use these stakeholder maps to put in place appropriate stakeholder-management strategies to focus your efforts in improving the impact of UX work. You can download a sample stakeholder mapping tool below to get you started with stakeholder analysis.

Reference

Mendelow, A.L., 1991. Stakeholder Mapping, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems, Cambridge, MA (Cited in Scholes,1998).

Resources

Stakeholder Mapping Template (Google Sheets)

Stakeholder Mapping Template (.xlsx)

Share this article: