It’s up to designers to use branding elements and interaction design guidelines to bridge the gap between Brand intention (the way a company attempts to construct its identity) and Brand interpretation (the way customers experience a Brand).

“Brand” vs. “Branding”

Though often equated, Brand (with an intentional capital “B”) and branding are different concepts. Brand is concerned with what value a company offers to its customers. Branding is concerned with who delivers that value (i.e., the identity of the company offering said value). (I’ve described this differentiation in the past as reputation vs. representation.)

To make these definitions more concrete:

- Brand (with a capital “B”) is a promise about what a company stands for, or, the value it offers its customers. For example, a specific Brand could represent a promise that its associated products might be "healthy,” “sustainably made,” or "durable."

- Branding can be defined as the controlled manifestation of the Brand’s identity through application of logo or other guidelines to advertising, communications, packaging, and so on.

For an example of these two concepts in action, let’s take a look at Google’s Material Design. Google’s intent behind this set of design specs and design elements was to extend its Brand mission, “to take the world’s information and make it more accessible,” to a growing range of devices and ways of communicating with its users.

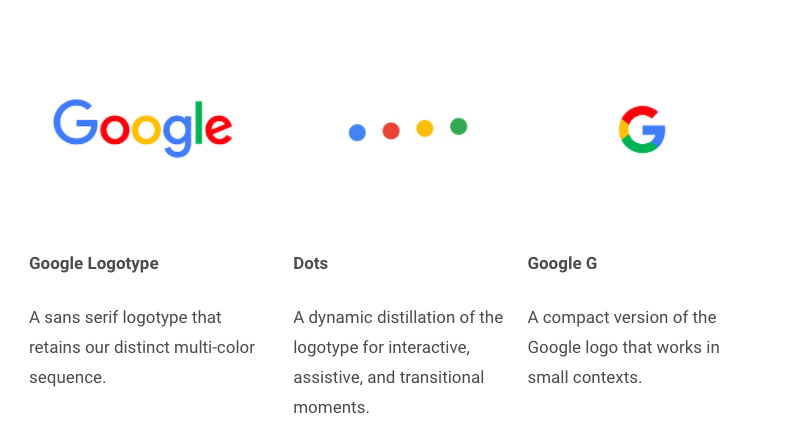

The visual language outlined in Material Design included an updated brand mark and logotype, as well as design elements, such as the set of four dynamic dots — components that evolved Google’s branding, and help express its brand identity.

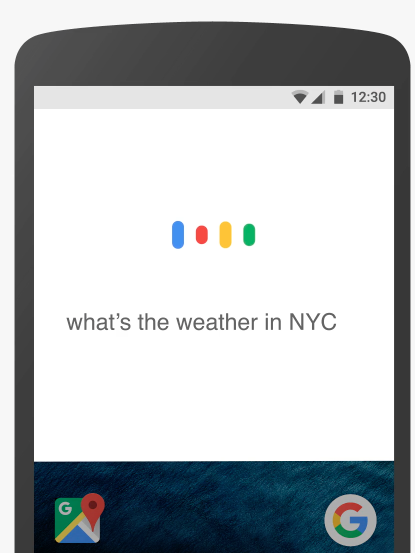

Designers extended these elements to create user interactions that aligned with Google brand attributes. The dot animations that reflect the “expressions” of listening, thinking, replying, incomprehension, and confirmation not only serve as a way to indicate system status (remember, this is one of the 10 usability heuristics), but they also help reinforce the Google Brand itself. The friendly, assistive nature of these interactions evoke brand attributes associated with Google—being helpful, efficient, and simple to use.

Company, Customer, Designer: What Role Does Each Play in Brand?

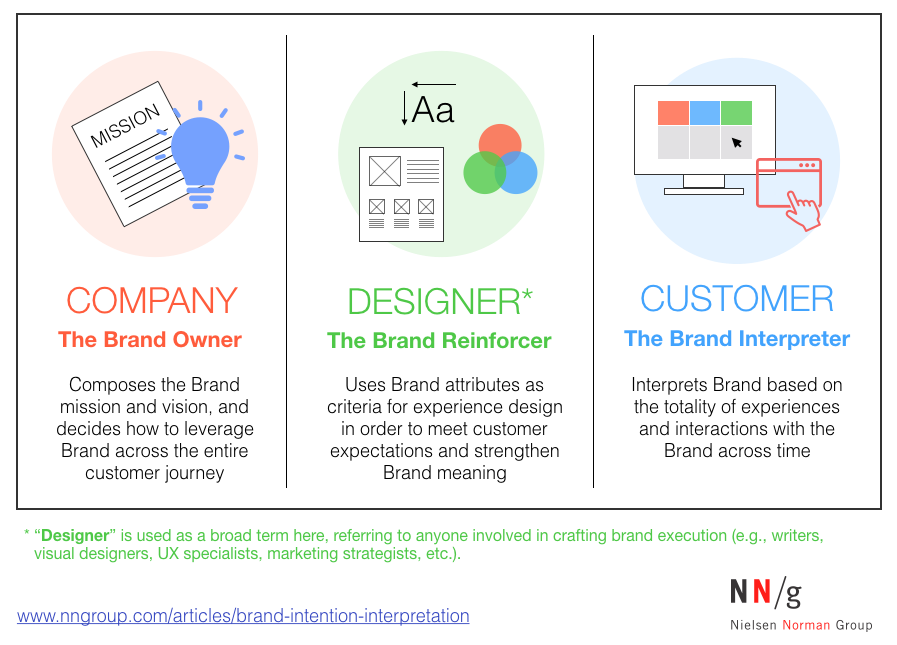

Brand is owned by the company, reinforced by the designer, and interpreted by the customer.

The Company: Brand Owner

The strengthening of consumer voices across a variety of channels (especially social channels) has led to an increasingly common conversation about who owns Brand: the company or its customers? While public consumer complaints often reach other customers and influence them as much as messages put out by the company, the company still owns Brand: it controls its vision and mission, manages its attributes, and makes decisions about how Brand is leveraged across the customer journey.

The Designer: Brand Reinforcer

The goal of any “designer” (e.g., visual or interaction designer, writer, UX specialist, or marketing strategist) should be to reinforce Brand meaning through experience design.

When approaching a problem or project, designers should be able to break Brand down into core components that inform design decisions. (However, this is admittedly often difficult, because Brand often starts and stops as a presentation deck in a board room, with only logos and guidelines made available to downstream design teams.) Core Brand components should drive design decisions (e.g., interaction design, visual design, content tone of voice, environmental design). Consistent crosschannel decisions that are aligned to Brand reinforce Brand.

The Customer: Brand Interpreter

However, consumers do define the Brand meaning for themselves, based on their own experiences and interactions with the company.

How customers interpret Brand is a function of:

- the actual value a company provides, and

- the experiences that they had over time and across touchpoints with that company.

People rarely experience Brand in isolation; they experience it over time in many situations and derive value from the totality of their experiences (i.e., over the entirety of the customer journey). If an experience does not match up to customers’ expectations, Brand is compromised.

How Can Designers Successfully Reinforce Brand?

1. Define core Brand components.

Two key Brand components must be defined: the Brand promise and the Brand attributes.

- The Brand promise (sometimes called Brand essence or Brand meaning) is the unique, foundational idea behind a brand that provides consistency for Brand identity.

- The Brand attributes (which, together, compile the brand personality) is a set of traits that inform everything from product or service development to identity systems.

The Brand promise is a function of the company’s vision, mission, and overall values (i.e., its core beliefs).

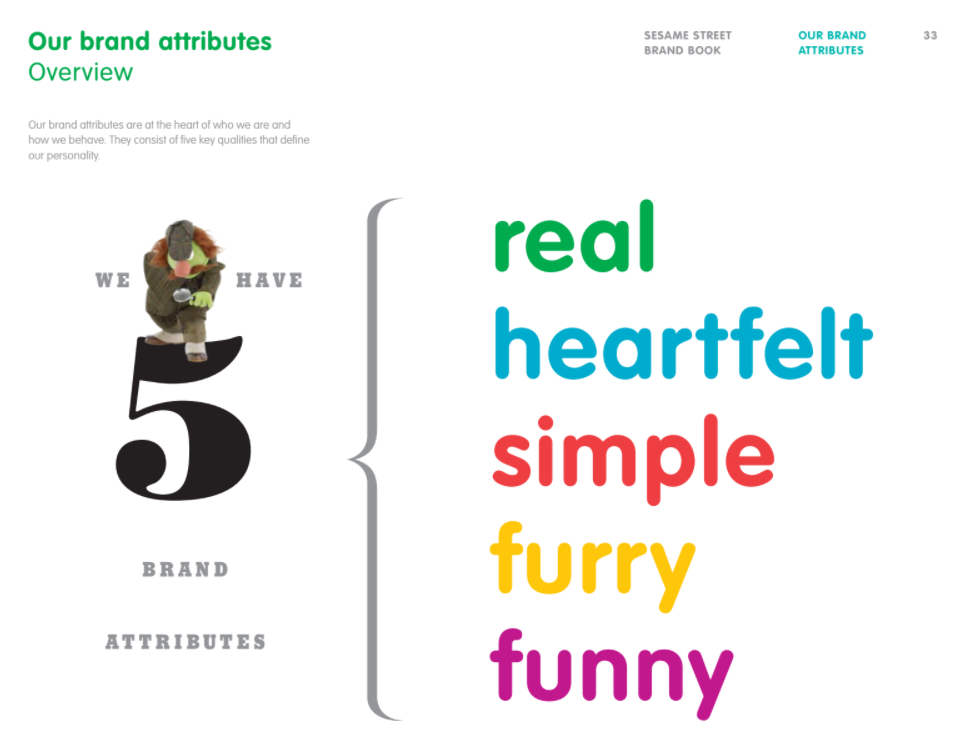

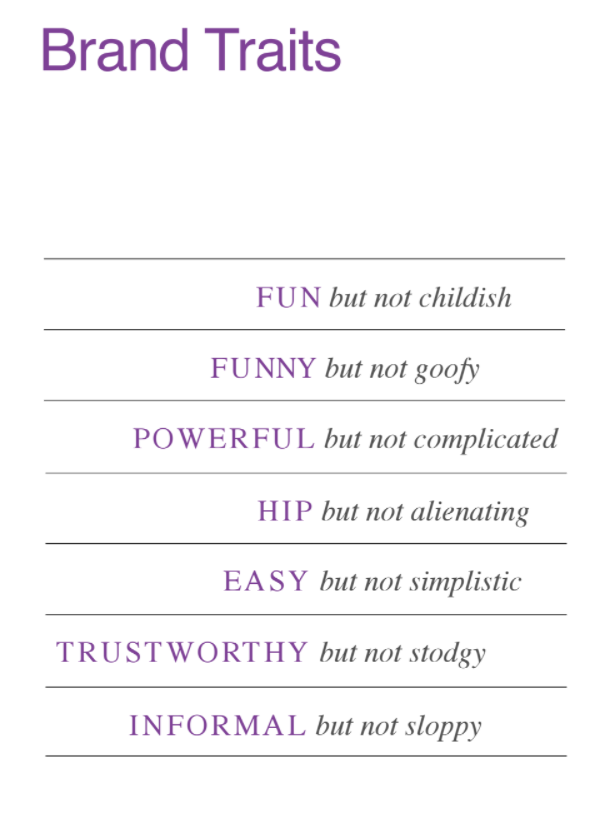

The Brand attributes are derived from the Brand promise, and describe the character of the Brand. They are typically a set of 3–7 words that express the essence of your Brand. Everything a designer produces (or a company does) should embody this set of words.

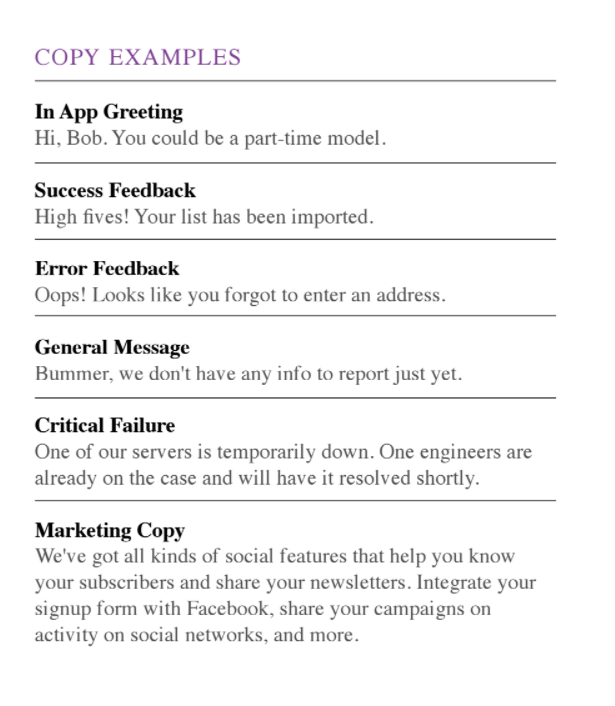

2. Create a framework to extend Brand attributes.

Too often, teams will stop after the articulation of Brand attributes, with no understanding of what those words really mean, or how to apply those concepts to product or interface design. Create a framework to support the meaning of Brand attributes and extend them to different areas of experience (sounds, typography, language, etc.). This framework turns attributes into effective criteria for developing and evaluating a customer’s experience with a Brand.

For example, the Sesame Street Brand pillar of “heartfelt” is extended with the association of “warm” and “genuine” (from the company’s copy) to further define the meaning of “heartfelt.”

Conclusion

Remember, your job as a designer (whatever type of designer that may be) is not only to produce a good use experience on each isolated channel. It’s also to ensure that every experience you design is made up of components driven by Brand. With key components defined, as well as a clear framework for how those components affect different areas of experience, Brand is more likely to be consistent across channels, and aligned to the intended Brand concept and attributes.

Share this article: