Since the iPhone was introduced in 2007, mobile usability has made tremendous strides: we use our phones to do a wide variety of tasks. In fact, according to Pew Internet, in 2019 17% of Americans depended on their mobile phone as their only way to access the internet at home. Those numbers are much higher in other parts of the world such as India or China.

We know that even when people have a larger device available, they sometimes prefer to use a mobile phone instead — simply because the mobile phone is always with them and it may be more convenient to use it instead of switching devices (a phenomenon we call device inertia).

But does it mean that mobile will displace computers? Will we eventually discard big-screen devices in favor of smaller, portable ones for tasks as complex as filing taxes or writing research reports?

In this article we don’t aim to answer that question: instead we assess the current state of device preferences. We look at the importance that people assign to activities done on different devices. Has mobile caught up with computers yet?

Methodology

As part of our Life Online research project, we asked 50 American respondents in a diary study to tell us what they did online in their daily lives. We obtained 492 different records of online activities. Each record included the following information from the respondent:

- A description of the activity

- If (and how) the activity influenced the respondent’s thoughts, opinions, or actions

- Whether the activity was for work, personal life, or school

- Which device(s) was used

- What the respondent’s motivation was for performing the activity

- A rating of how important the activity was to the respondent, on a 1–5 scale, 5 being the most important

- How the respondent felt about the activity

- How long it took

- Whether the activity was successful

- How easy the activity was for the respondent, on a 1–5 scale, 5 being very easy

This dataset allowed us to investigate which devices people use to perform their most important online activities.

Larger Devices Are Used for Important Tasks

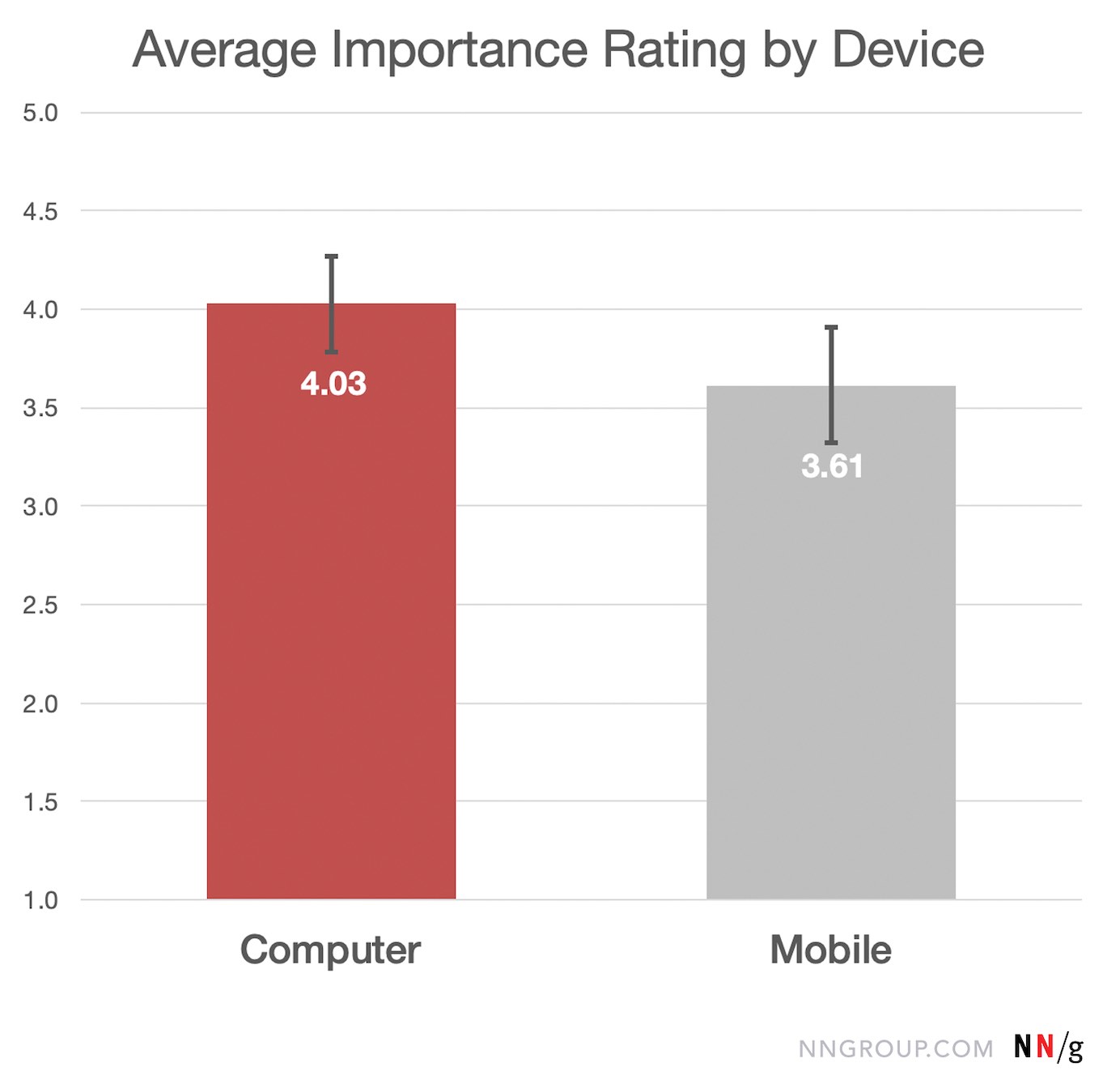

We found that the activities carried out on large-screen devices like desktop computers and laptops were considered more important than those performed on smartphones.

This data says that people tend to do important tasks on the bigger screen, but it doesn’t tell us why they do it. It could be that many of the important tasks are not supported on mobile devices. Or, more likely, it could be that the overall experience of doing these tasks on mobile is perceived as too bad, so people prefer doing these important tasks on bigger devices. In cases where the stakes are high and mistakes could have severe consequences (e.g., doing your taxes), people may feel safer and less error-prone on larger screens.

To throw some further light on this, we looked at the average task-difficulty rating on desktop versus mobile. Task difficulty is often used in quantitative usability testing as a measure of usability; however, it also indirectly reflects the complexity of the task (with complex tasks tending to get higher difficulty scores).

We found that respondents rated mobile activities as easier than computer activities on average (and this difference was statistically significant).

We don’t believe this is because mobile usability as a whole is better than desktop usability. Instead, our interpretation is that users decide to solve their easier problems on their phones and turn to their full-size computer for the more difficult tasks. (Remember that we did not impose the same tasks on both devices, because this study was conducted in the field and was not lab-based. Study participants chose which activities they did and what device to use.)

Together with our finding that mobile activities tend to be rated as less important than computer ones, this result suggests that, unless we can make important tasks easy and fail-proof, people will avoid doing them on mobile devices.

Mobile Constraints Still Limit the UX for Complex Tasks

Given the substantial improvements in mobile UX in recent years, these findings may seem a little surprising. There are three changes, in particular, that might make it puzzling: Mobile screens are now bigger, people use their mobile devices more frequently, and mobile products now support a wide variety of functionality.

- Bigger, faster smartphones: In the past, mobile site and app experiences were severely limited by small screens and slow processors, making them fit for little more than media consumption and entertainment. However, today’s smartphones have more than 30-times the RAM of their predecessors, and screen sizes have increased to close to 7 inches.

- Heavier mobile use: Today, smartphones play a larger role in our lives, and as a consequence, users are more familiar and comfortable with mobile than they used to be. For example, in 2010, researchers at the University of Alberta found that reading comprehension was impaired when people read content from a mobile device. When we conducted a similar study in 2016, we found no practical differences in the comprehension scores on easy passages, whether participants were using a laptop or a mobile device. In our interviews with those participants, some people reported that they actually preferred to read on a mobile device, since that was how they normally read news and other content.

- More support for tasks on mobile: Many modern mobile experiences and products support some important and complicated activities. For example, you can apply for a home loan (typically a fairly complex task) through a mobile app.

- Optimized mobile apps: Some tasks have dedicated support through special applications that are optimized for mobile use and are typically not offered on computers at all. For example, it can be faster to check a bank account balance through the bank’s dedicated app (once installed and configured, of course) than to perform the same task on the bank’s website on a computer.

Despite these product and device improvements, we still found that users choose to do their more important internet-based activities on their larger devices. We suspect that the various device constraints still limit the complexity of the activities that can be done on mobile, essentially degrading the user experience of those tasks deemed as important:

Size: The relatively beefy over-6-inch smartphones available today still pale in comparison to the average laptop screen, let alone a 32-inch desktop monitor ($199 at Walmart these days). Less content in each screenful means less context and a higher cognitive load for users.

- Input: Typing on mobile devices is still a pain. Even alternative input options like swipe keyboards and voice-to-text are often inaccurate and slow users down. Users fear making mistakes and anticipate the interaction cost of data entry on their mobile devices. Particularly if the activity is personally important (like an important email to a client), users might choose a larger device to avoid mistakes.

- One task at a time: Although many mobile operating systems now offer a split-screen mode, the small screen size limits its usefulness. The fact is, in most cases, users on mobile devices must focus on one window at a time. This limitation means that it’s difficult to combine multiple sources of information and carry out complex tasks. These mobile constraints are no problem if the task is simple, unimportant, or open-ended. However, when the task is goal-based and has high stakes, these constraints are reason enough to save the task for another device. These limitations are likely to stick around for the foreseeable future, despite continued hardware or product improvements, and may continue to influence user behavior.

| Desktop/Laptop | Smartphone | |

| Constraints | Not portable |

Screen size, input methods, one task at a time |

| Strengths | Large screens, processing power, inputs, and controls | Portability, camera inputs, GPS, ease of biometric login (fingerprint or facial recognition) |

| Context of use |

Important, and complex activities, research tasks, long-form text, and data entry |

Smallest tasks, spur of the moment activity, on-site and away from home activities |

Just as device constraints limit certain tasks, device strengths also encourage certain tasks. This table shows how strengths, constraints, and context of use influence which device users may select for an activity.

Context of Use Influences Which Activities Users Complete

When people are away from their desks or homes, the smartphone becomes their primary device. But, while on-the-go, users typically do not have long chunks of uninterrupted time to focus in on an important task. They pick up their phone between meetings, while waiting in line at Starbucks, and while sitting at stop signs (naughty!), to fill small sections of empty time.

At home or at work, people can engage in longer sessions without having to attend to an external interruption, and thus they can focus in on important activities. And often, for these important activities, they will turn to the reliable-input, larger-screen devices.

Even though people will occasionally start complex activities on smartphones, in many cases they will switch to a better suited device.

For example, a person might receive and email on her mobile device to sign up for a CPR training course. She might begin the registration on her phone, but wait to complete it at home due to the amount of data entry she encountered. (This is one reason we recommend a seamless omnichannel user experience.)

Designing for Mobile Is Still Critical

All of this does not mean that people won’t try to complete important or complex activities on mobile devices, but they often prefer to use a larger device when given the option. When users don’t have a choice or if the phone is their primary device, they still need and expect to be able to perform key actions on their smartphones.

Note that this study included participants older than 18 years. In our studies of teenager behavior, we’ve found a strong reliance on mobile — partially because most teenagers now own a smartphone, but not all own a laptop or tablet. Depending on your target audience, higher or lower proportions of your users will attempt to perform important tasks on mobile.

If your product supports activities that users might consider of high importance (finance or healthcare, for example), check your analytics. What proportion of your users are mobile? If the volume of your interactions on mobile is low, definitely avoid a mobile-first strategy. You still need a mobile presence, but that likely shouldn’t be your design team’s top priority. If you’re unsure which tasks your users consider important, run a diary study asking people to rate various activities by importance. This methodology will also allow you to get more context from users as to why they choose one device over another for key activities that your products supports. Arming yourself with this knowledge will help you prioritize the work and resources you dedicate across each experience.

Share this article: