Let’s imagine that you’re waiting for a friend outside a restaurant. A person wearing a security uniform comes up to you and says, “See that man over there? He’s over-parked, but doesn’t have any change. Go give him a dime.” Would you give him the dime? Statistically speaking, you probably will; 92% of the participants in this study, done by Leonard Bickman in 1974, did. However, when the requester wore civilian clothes, that percentage dramatically decreased to 42%. (Same person, different outfit = huge difference in influence.) This is the authority principle at work.

In his book Influence: Science and Practice, Robert Cialdini identifies six principles of influence:

Definition: The authority principle refers to a person’s tendency to comply with people in positions of authority, such as government leaders, law-enforcement representatives, doctors, lawyers, professors, and other perceived experts in different fields.

The authority principle is an example of the human tendency to use judgment heuristics. In this case, the implicit assumption is that those in positions of authority may wield greater wisdom and power, and therefore, complying with them will lead to a favorable result. As humans, we are inclined to make the easier decision rather than the accurate, more effortful one.

It’s not hard to understand the source of the authority principle. As children, a lot of our knowledge about the world comes from authority figures such as parents and teachers. For example, if a child wanders up to a very hot cooktop, the parents will warn her not to touch the stove. The child trusts the adult’s reasoning skills, and doesn’t burn her hand. Or, if a teacher says that 1+2=3, the child trusts the teacher’s authority on the matter. Even now, as adults, we see or read about people in positions of authority accomplishing great results with their competence. While we do grow more skeptical as adults, we still tend to consider the judgment of certain authority figures, like scientists, doctors, lawyers, and law-enforcement people, to be more reliable than our own, even on matters that are outside their domain of expertise.

Milgram Experiment

An article about authority and obedience would not be complete without referencing one of the quintessential social-psychology experiments on the topic. In Stanley Milgram’s famous experiment, participants were asked to conduct a series of memory tests on another person who, unknown to the participants, was a confederate of the researchers. The participant was told to administer a series of electric shocks to the confederate each time the confederate failed to produce a correct answer to the memory task. The shock voltage levels increased as the test progressed. (The confederate did not actually get shocked, but the participant was led to believe that he was.) As the voltage increased, the confederate began to plead with the test subject to end the shocks, and even went as far as pretending to be unconscious. If, at any time, the participants wanted to stop the experiment, a researcher in the room prompted them to continue. The actual test subjects would then face a conflict of whether to comply with the scientist or to end the shocks. Unfortunately, 65% of the participants ended up proceeding to the highest level of shocks (even though the highest levels were labeled “Danger: Severe Shock” and “XXX”).

The Milgram experiment revealed a tendency to rely on authority figures when making decisions, even when those decisions are immoral. While this experiment did come under fire in later years for its deceptive nature, it allowed us to understand human behavior and what compels us to sway our opinions and decisions.

Authority and UX

Although obedience to authority can lead to misjudgments and unethical behaviors, it is not always bad: after all, relying on expert opinion is an effective decision-making shortcut in many situations and saves us the work of researching the matter ourselves.

For example, a user may have to accomplish a complex, information-heavy task of comparing products in realms where extensive education or professional development is needed: financial services, legal services, or medicine. In times of uncertainty, users may look toward authority figures in these domains in order to inform their decisions.

UX professionals can take advantage of the authority principle to increase the credibility of their designs. Here are a few elements that can increase trust:

- Photos of people in authority positions (or people dressed like they’re in authority positions) — doctors or scientists dressed in white lab coats, or lawyers dressed in suits

- Symbols of authority — for example, the caduceus or staff of Hermes, a popular symbol for the practice of medicine, or the scales of justice for law-oriented sites

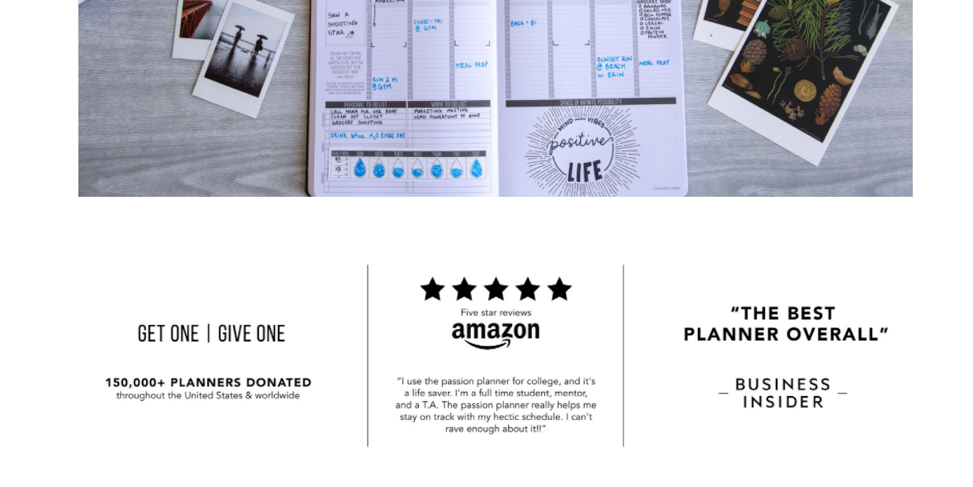

- Logos of reputable organizations

- Quotes and endorsement from experts, celebrities, and other authority figures

Successful Examples of Authority in UX

Ethical Considerations of Authority

Using the authority principle to your advantage does not mean you’re free to deceive your customers with false authority pretenses. There are, after all, ethical standards we should uphold in the field of UX. We should consider, first, if we are being helpful and honest in our use of authority. Is it helpful and honest to say that Andrea Bocelli, the famous Italian tenor, endorsed a math-tutoring software? Or would it be helpful and honest to say that a few officers of a police department recommended a catering service to their friends? Even if these endorsements are true, these people are authorities in unrelated fields, and their opinions, although likely to sway our audiences, do not represent true expert assessments for the quality of the corresponding products.

It’s also important to ensure we do not violate client-confidentiality agreements by posting client logos. Sometimes proprietary information and advising/consulting business relations may hinge on maintaining nondisclosure agreement. Consider whether your endorsements and “past clients” section features companies which have agreed to be publicly affiliated with your organization. If not, work to obtain permission before plastering their name on the home page (or any page).

If the temptation arises to utilize dark patterns or deceptive techniques, consider the golden rule of ethics in UX design: “Ask yourself whether your technology persuades users to do something you wouldn’t want to be persuaded to do yourself.”

Conclusion

We can use the principle of authority to help alleviate the strain of decision-making. Persuasion and influence are not only about swaying customers to make decisions the business wants (though that’s certainly part of it); they are also about decreasing the amount of thought, second-guessing, and effort that goes into decisions that users already want to make. By reducing the effort required to make a decision (and then reaffirming that decision), we can increase user confidence and empower our customers. Remember, empowered customers are happy customers, and happy customers are paying customers.

References

Bickman, L. (1974). The social power of a uniform. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 4, 47-61.

Share this article: