Traditional roadmaps originated in the early 1900s as motorist aids. The first roadmaps listed instructions: how to get from one town to another, where to find gasoline, and where to find a repair shop. Today, many of us use roadmaps routinely, even though nowadays they’ve become digital.

In 1987, Motorola introduced the term “technology-roadmap process” — a process to produce and document product strategies that met market needs. In the early 1990s, roadmapping grew in popularity among hardware and software companies as a way to plan and communicate upcoming work. Since, roadmaps have fallen in and out of popularity. Regardless, the same need has persisted — a way to align, prioritize, and communicate product strategy and future work, to both team members and stakeholders.

This article will provide an introduction to the use of roadmaps within UX.

What Is a UX Roadmap?

Definition: A UX roadmap is a strategic, living artifact that aligns, prioritizes, and communicates a UX team’s future work and problems to solve.

A UX roadmap should act as a single source of truth representing your UX team’s North Star. It helps your designers, researchers, developers, and stakeholders align around a single vision and set of priorities.

Roadmap Structure and Primary Components

Roadmaps can take several tangible forms: organized lists, spreadsheets, slide decks, high-fidelity visualizations, sticky-note walls, or even a mix of media.

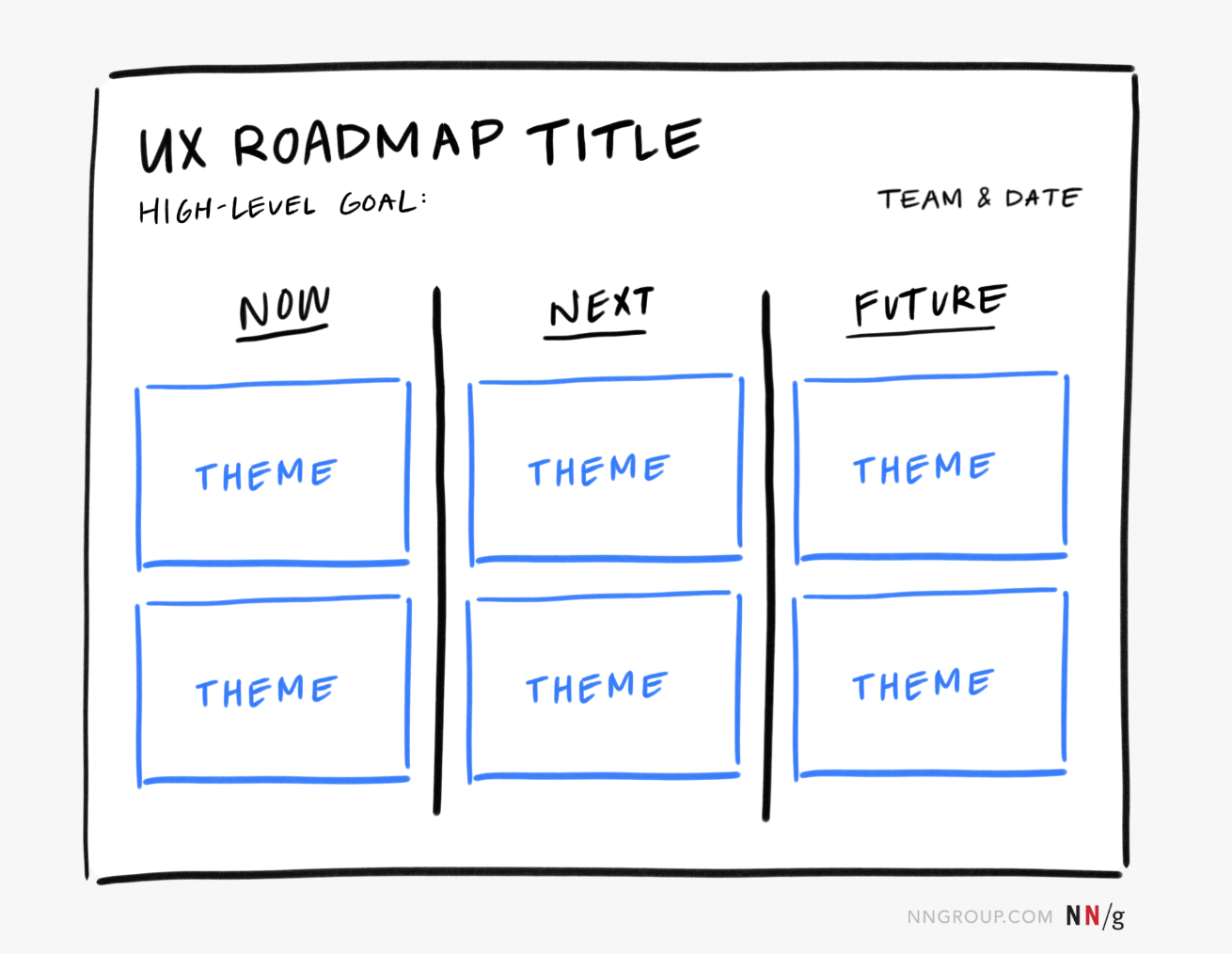

Thus, not all roadmaps look alike. However, regardless of visual appearance, all UX roadmaps generally share the same fundamental structure — they are organized by context (scope and time) and theme. Think of this structure as the scaffolding for your roadmap:

- The context dimension frames the meaning and use of your roadmap so it can be fully understood by anyone who reads it.

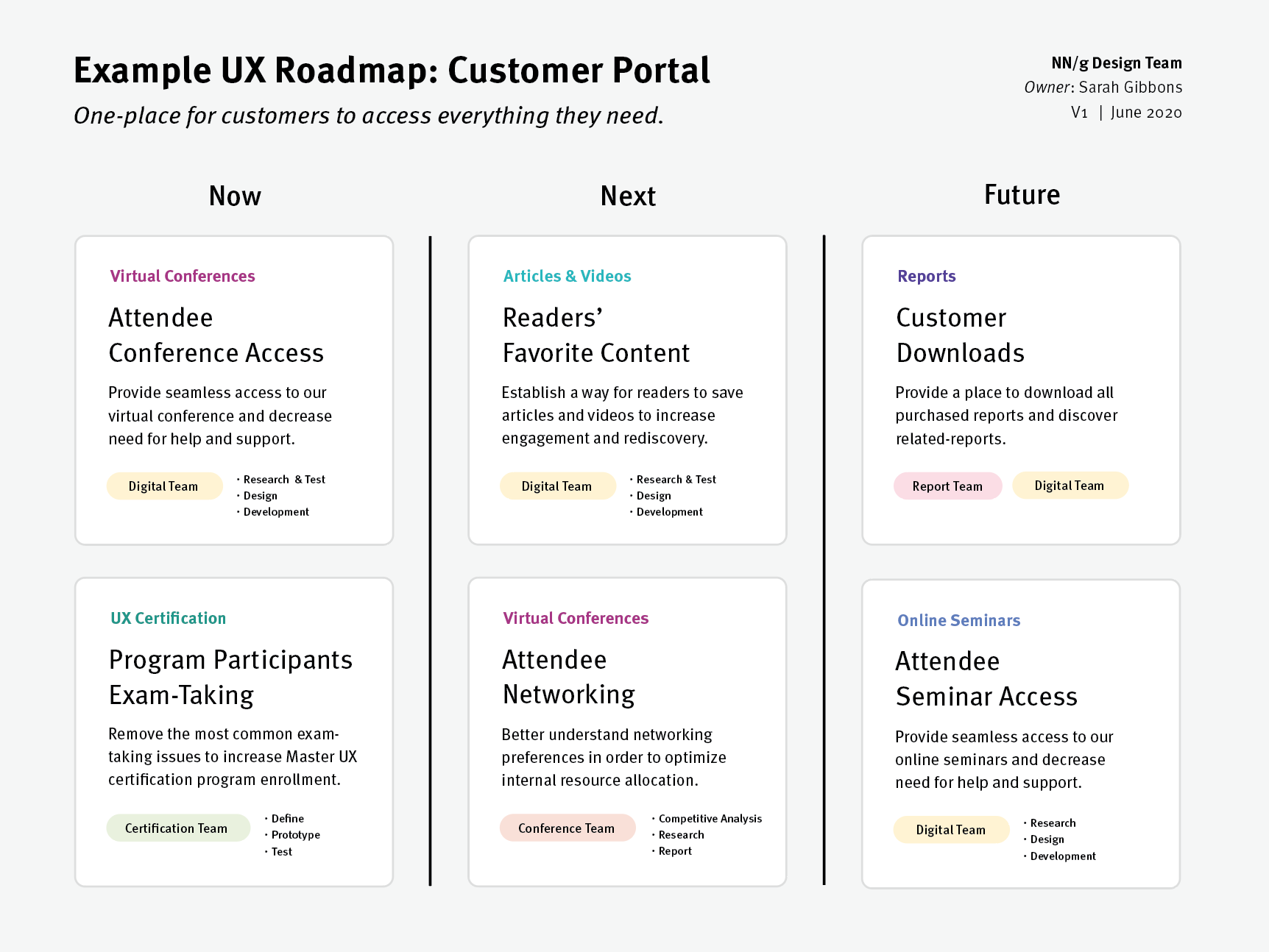

- Scope gives the artifact an owner and purpose and has several components:

- Title: The product or portfolio team the roadmap will be used by (likely a mix of researchers, designers, and potentially developers)

- Roadmap owner: The team (or person) who created the roadmap (i.e., who should a question about the roadmap be directed to?)

- Date: When the roadmap was created or last updated

- High-level goals (or vision): A broad company (or organization) strategy that the roadmap works towards

- Time provides the roadmap with a timeframe and includes 3 horizons:

- Now: UX work (research or design) that is in progress and will be completed in the immediate future; this work is well-defined and more specific in nature

- Next: near-future work

- Future: UX work that is 6 or more months away (Themes in this horizon are most likely to change and ambiguous in nature.)

- Scope gives the artifact an owner and purpose and has several components:

- The theme dimension represents future UX work, including are areas of focus, initiatives, or problems to be solved and plugged into a corresponding time horizon depending on when the work is going to be completed.

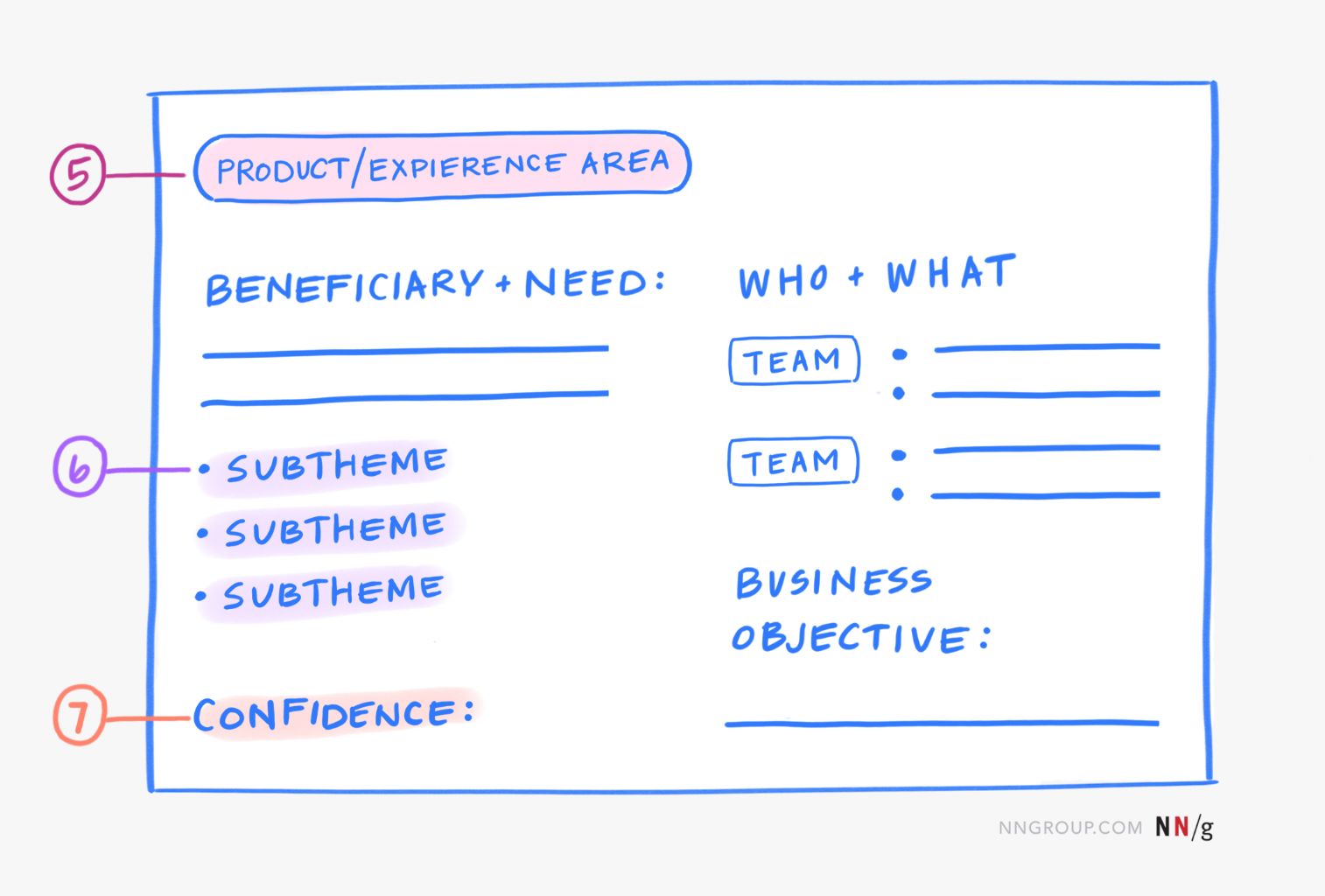

Themes are high-level bundles of work and should include 3 components:

- Beneficiary and need

- Beneficiary: The prioritized recipient(s) of the UX work (e.g., end users, fellow employees, or even internal stakeholders)

- Need: The problem that will be solved (the purpose of the UX work)

- Business objective(s): Objectives and potential outcomes (from a business point of view) that will be achieved upon completion (e.g., new market insight, user growth, increased engagement, ease of discovery, revenue, etc.) — think of these as success metrics for the work

- Ownership

- Who: The person or team who will complete the work

- What: At a high-level, the kind of work that will need to be done (by the who); this should not be discrete task list, but rather a bulleted list of work breeds (e.g., discovery research, workflows, visual design)

Secondary Components

Beyond primary components, there are secondary components that can be added to UX roadmaps, depending on the context and audience:

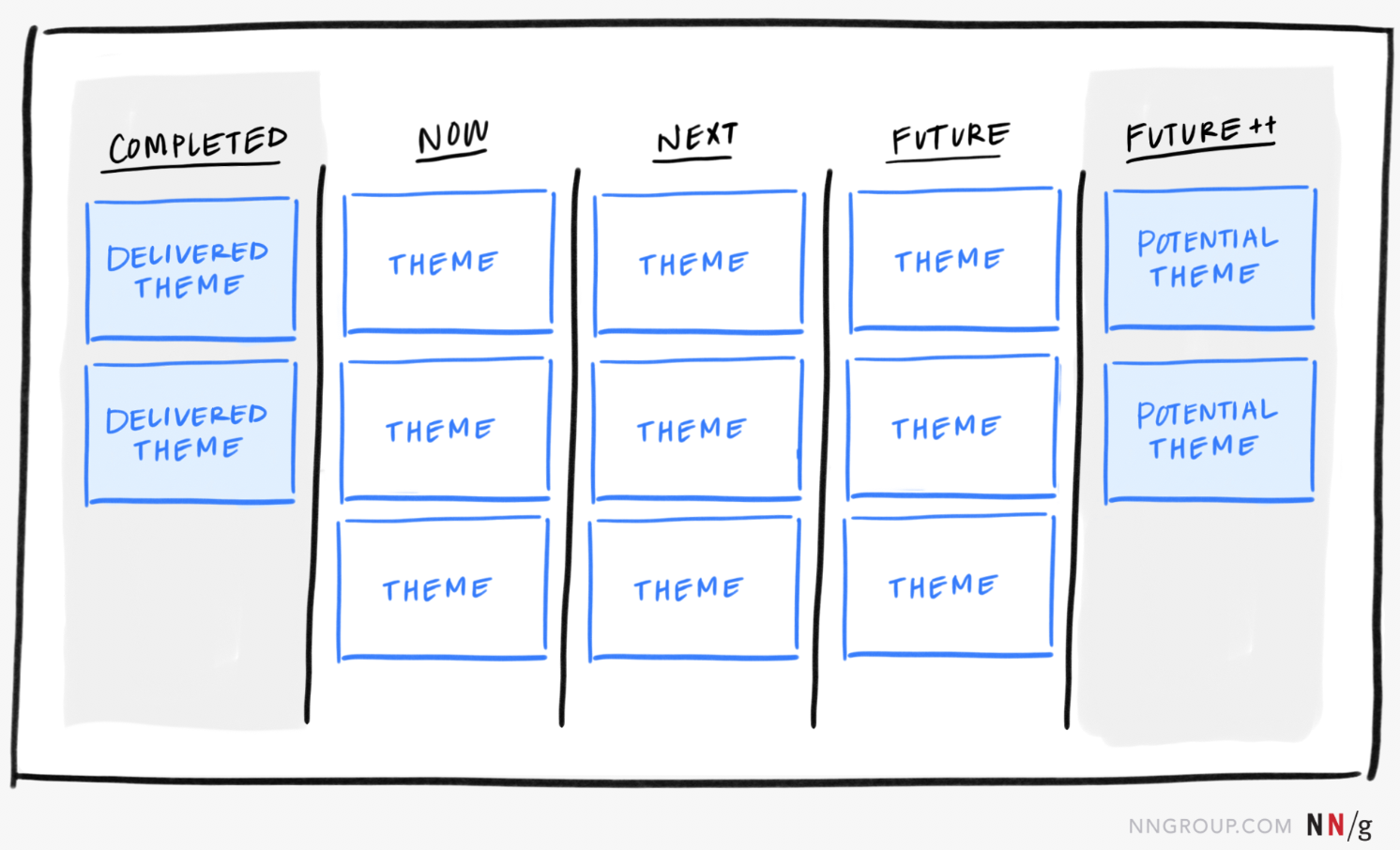

- Completed and Future++ are two additional time horizons (think pre and post roadmap scope). Completed shows UX work that was just previously delivered, while Future++ is UX work that can potentially be placed in the Future column.

- Product areas is the area of the product the UX work will touch. Product areas are included when the product, experience, or service is complex and has many different components (e.g.,touchpoints). The naming system for product areas should align to the language of the audience using the roadmap. For example, for a product like Facebook Marketplace, product areas could include Groups, Stores, Buying, or Selling. In the above NN/g UX roadmap, product areas include Virtual Conferences, Online Seminars, UX Certification, and Reports.

- Subthemes are specifics added to a larger theme: multiple subgoals that the theme encompasses, a specific user segment or persona, predetermined solutions from past work, or discrete features already tested and validated. Subthemes are most often included within themes in the Now column, where themes tend to be discrete and tangible because they are already in progress.

- Confidence estimates are informal assessments of likely impact and demonstrated need for the different themes. Low-confidence estimates are typically attached to items based on assumptions or open questions, while high-confidence estimates are assigned to work validated by research or other data. Thus, if the item is supported with previous research and insights, consider giving it a high score on a confidence grading scale (e.g., 6/7). If the item is highly exploratory and lacking previous research, consider assigning it a low-to-moderate score of 4/7. Confidence estimates allow stakeholders to understand what items in the roadmap build on previous work and what items are a bigger bet (but have potential to differentiate your user’s experience from others).

- Disclaimers state requirements or risks associated with a theme or component of the roadmap. They can be included within a theme or applied to the roadmap as a whole. The number of disclaimers is often directly proportional to the number of people who will be see the roadmap — the more public the roadmap, the more disclaimers.

Adaptations

UX roadmaps are a malleable tool. They should be adjusted based on how the roadmap is going to be used and by whom. Roadmaps are most commonly adapted by shifting the scope and lens.

Scope. Roadmaps can be narrow or broad. A narrow roadmap focuses on a singular initiative, while a broad roadmap covers a portfolio-wide UX redesign or the conception of a completely new service. The more granular the scope, the more concrete the time horizons in the roadmap (the Next column may be completed within the next 6 months and is less likely to change). Conversely, the broader the roadmap, the longer the time horizons (the Future column will be completed in a year or more and is highly likely to change).

Lens. Roadmaps can depict UX work through different lenses — commonly, by expertise or by product team. For example, a UX research manager may create a year-long roadmap for a group of researchers serving multiple teams. Themes would include planning, conducting, and analyzing research across multiple products within the organization. Alternatively, a roadmap can also be created through the lens of a specific product. In this case, the themes can include work across expertise (e.g., research, content strategy, and design), but all within the same product.

Roadmaps vs. Similar Concepts

Roadmaps vs. Release Plans

Roadmaps and release plans have two different purposes and thus should be two different documents. Roadmaps are strategic artifacts that communicate a vision — the problems that will be solved. Release plans are execution artifacts that discuss what features will be delivered in upcoming releases. Roadmaps should answer “What we should solve for?” while release plans should answer “How should we solve it?”

Roadmaps vs. Project Management Plans (Including Kanban Boards)

Similar to release plans, project-management plans and Kanban boards, are execution and tracking artifacts, whereas roadmaps are strategic, vision documents. Kanban boards, popularized by David Anderson and used predominately in Agile project management, keep track of tasked work. While both UX roadmaps and Kanban boards share the same format — time-oriented columns and work-item owners — the items within the columns differ in granularity and purpose. Roadmap items are high-level problems to be solved. They establish the product vision. Roadmap items lack formal, discrete task definition and likely represent a range of potential future work (from research, to analysis, to design and development) that has yet to be defined. Project-plan items are specific, low-granularity, less likely to change, and often include discrete, measurable tasks. Think product (roadmap) vs. project (Kanban board).

Roadmaps vs. Product Backlogs

A product backlog is a ranked list of detailed development tasks to be completed, including customer-facing needs and infrastructure needs (things never seen by customers). Backlogs are an evolution of traditional requirements documents and are used as development teams’ master to-do list. An effective product backlog breaks down a roadmap’s high-level vision into actionable items that the development team can accomplish. (Note, product backlogs are often used in Scrum, where limits are imposed by time.) Roadmaps should be used to help inform prioritization decisions for backlog items.

Roadmaps vs. Customer-Journey Maps

Even though both share related words in their names (“road’ vs. “journey”), the two concepts are very different, both in purpose and organizational structure. Roadmaps are used by UX teams to communicate future work (within their team and to stakeholders). Customer-journey maps are used to understand users’ journey as they interact with a product or service. A journey map’s structure aligns to the timeline of the use, while a roadmap’s structure follows a Now, Next, Future structure.

Characteristics of Successful Roadmaps

Roadmaps are successful when they make realistic promises, value functionality over pretty visuals, or are strategic documents instead of feature-specific release plans. Successful UX roadmaps should be:

- Based on user research. Even though roadmaps are most commonly used internally as alignment artifacts, they should still be user-oriented. If we think about themes as user problems to solve, the problems plugged into a UX roadmap should be derived from a mix of qualitative and quantitative research. Don’t forget, not only should the themes in the roadmap be driven by research, but the roadmap should also specify future research that needs to be done (and which would theoretically drive themes in a future roadmap).

- User-focused, not feature-focused. Remind yourself, and others, to prioritize outcomes over outputs. Roadmaps should not map out every specific feature, which is likely to lead to unrealistic promises or prevent positive design iteration. Map the high-level initiatives instead.

- Contextually appropriate. Roadmaps should be rooted in your organization’s larger strategy. They should be adapted to the needs of its audience; utilize specific secondary components as necessary.

- Collaborative and living. Just as wireframes are prototypes for future websites and service blueprints are prototypes for future processes, roadmaps are prototypes for strategy over time. It is important to set the expectation that themes on the roadmap (especially those further in the future) will potentially change as new variables and insights arise. Ideally, build your roadmap with input from others to increase buy-in and support.

Conclusion

If you are taking your company’s feature wishlist and applying it to a specific timeline in a tidy Excel spreadsheet, you’re doing it wrong. A UX roadmap is not a release plan, it is a strategic document. It should act as a single source of truth amongst designers, researchers, developers, and stakeholders to define, organize, prioritize, and then communicate future work towards your UX team’s vision.

Learn more in our full-day course on UX Roadmaps at the UX Conference.

Resources

Lombardo, C. Todd, et al. "Product Roadmapping: a Practical Guide to Prioritizing Opportunities, Aligning Teams, and Delivering Value to Customers and Stakeholders." O'Reilly, 2017.

Moore, Geoffrey. “Crossing the Chasm.” Collin Business Essentials. 1991.

Willyard, Charles; McClees, Cheryl. Motorola's Technology Roadmap Process, Research Management. 1987.

Share this article: