Putting aside direct transactions (such as online banking), user behavior in relation to internet content is paradoxical:

- Users go to websites for information.

- Users scarcely read anything during an average website visit.

This second point has been well supported by tons of research over the years:

- In 1997, the world's first study of how users read web content summarized the findings in two words: they don't. Instead of carefully reading information, users typically scan it.

- In 2006, eyetracking research found that users frequently scan website prose in an F-pattern, focusing on words at the top or left side of the page, while barely glancing at words that appeared elsewhere.

- 2008 research quantified this finding: given the duration of an average page view, users have time to read at most 28% of the words on the page.

Such research findings have led us to study nanocontent issues, such as how to cram maximal information into the first two words of headlines and links.

Being concise and frontloading keywords with high information scent remain key web-writing guidelines. Still, users sometimes do read more than the bare minimum, and we wanted to find out why.

When People Read

To investigate this phenomenon, we analyzed 1.5 million eyetracking fixations from hundreds of sites. The very fact that users allocated 1.5 M looks to these sites indicates that people actually do consume information on the web.

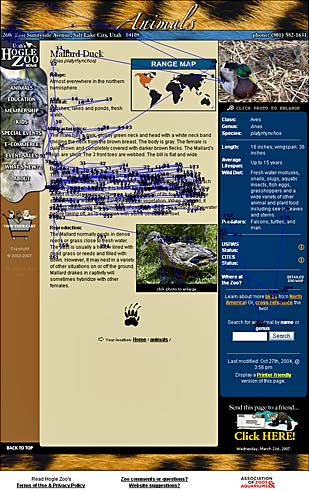

Case in point: this visitor to a zoo’s website read one paragraph exhaustively:

Of course, this example also illustrates the usual finding: the user didn't look at lots of information on the page. This was a well-structured page, with clear headlines delineating various pieces of information about a particular type of duck: its range, habitat, characteristics, behavior, and reproduction. In this case, the user was interested in the duck's behavior, so she read that paragraph in depth, while treating the other paragraphs to ruthlessly abbreviated scanning.

It's good that the user could focus her attention on the information of interest and ignore the rest. When we see people read on websites, it's usually because the site meets two usability goals:

- Good information architecture (IA), with clear navigation that allows users to quickly get to a page that's relevant to their interest. If users are bogged down by slow or misleading navigation, their interest peters out — as does their motivation to read much once they finally arrive on the desired page. Furthermore, each page should be clearly signposted, with a good heading and other design elements that signal that this is indeed the page users need.

- Good page layout that quickly guides the eye to the relevant part of the page, utilizing well-written subheads to summarize the information in each segment (as in the zoo example).

Importance of Being First

In the eyetracking example from the zoo’s website, the user read the page’s 4th paragraph because it contained the target information. In general, though, users pay the most attention to information at the top of the page.

The following table shows the percentage of users who looked at a paragraph relative to its sequential location in the body text:

| Position from the start of the text |

Users who looked at the paragraph |

|---|---|

| 1 | 81% |

| 2 | 71% |

| 3 | 63% |

| 4 | 32% |

This table counts only whether a user looked at a paragraph — that is, had at least one fixation within it. Quite often, such looks were part of a scanning strategy that didn’t lead to actual reading unless the content was deemed interesting.

As the table shows, the first 3 paragraphs all got a decent amount of attention, but it's striking that only 32% of users looked at the 4th paragraph.

The Value in Being Second on SERPs

Users behave in much the same way when viewing a SERP (search engine results page). It's extremely well documented that the first SERP hit gets disproportionally many clicks; few users ever even go past the first page of results.

Users tend to focus on the top hits, but they do look around a bit more than indicated by their click patterns: 17% of users look only at a single SERP link before they click, yet 42% look at the second and/or third hit.

Of course, looking at 3 hits on a page with 10 organic links and a bunch of ads isn’t much, but that's the majority behavior. To the extent that you believe in the branding value of people seeing your entry even if they don't click it, there's decent branding to be had from appearing as hits #2 and #3 in major search engines.

There's even some branding value in appearing further down the first SERP, because 12% of users look all the way to the bottom of the page. (Only 2% look at search results beyond the initial page, so there's minimal branding to be had — and even fewer clicks — if you're not on the first page.)

As when reading body text, user interest drops off quickly on SERPs: 18% of users look at the 3rd organic link, but only 8% make it to the 4th link. (All these numbers indicate is whether users' eyes fixated on the link, not whether users clicked it; clicks are even more concentrated toward the top.)

Good IA, Good Layout, Good Writing

As I mentioned earlier, helpful IA and effective page layout are key to getting users to read your copy. However, our eyetracking data also detected a third ingredient for converting users from scanners to readers: high-quality writing.

Sorry, no real surprise — although we’ve identified detailed guidelines for web content, they really boil down to that. Having guided people to your content, it must be good.

But good web content isn’t just about excellent prose. Quality digital content goes beyond print needs to include clear headlines and other elements that help users save time by focusing their scanning eyes on information that they actually want to read.

Full Report

Full eyetracking report on how users read on websites is available for download.

Share this article: