One of the biggest traps in product planning is focusing on outputs over outcomes — that is, discussing what to build before clearly defining its purpose. (As Jakob Nielsen said, a wonderful interface to the wrong features will fail, so even if you build that thing well, it won’t succeed.)

Despite the increase in design awareness, many apps and websites fail because they solve problems that nobody cares for. Before you decide on specific products and features, you should know the problem you need to address. Otherwise, you’re taking huge risks in building the wrong things.

Focus on Outcomes not Outputs

An output is a product or service that you create; an outcome is the problem that you solve with that product. For example, for a B2B website, an output could be whitepapers and demonstration videos. The outcome could be knowledge gained by customers. Unless you know what information people need and how they will use this information, it is premature to say whether or not a whitepaper or video is the correct solution.

The distinction between outcome and output is related to the classic difference between feature and benefit: a feature is something a product or service offers, whereas a benefit is what customers actually want. One of the oldest lessons in marketing and persuasive writing is that you sell more by emphasizing a product’s benefits instead of its features. Long feature list? Yawn. Benefits that solve users’ current pain points? They’ll give you their credit-card number right now.

In 1923, architect Le Corbusier wrote that a house is a machine for living in. That’s another way of saying that the features (everything that goes into designing and building a house) are subordinate to what we now call user experience (the benefits that accrue to the client who gets to live in the house).

Of course, benefits come from offering the right features. That’s why companies know their features inside out and why less-skilled marketers easily fall into the trap of promoting these well-known (to themselves) features. To understand benefits, you have to understand customers, and only good marketers do that.

Similarly, in UX design, we absolutely must create the outputs. Only by making the system do something can we make it support users in accomplishing their tasks. Therefore, outputs are an undeniable necessity. Moreover, because we work so hard on producing the right outputs, it’s tempting to make them the center of the design project.

In contrast, defining a desired outcome requires a deep understanding of users’ problems and an approach to solving them, using UX techniques like personas and journey mapping. But the output space is more tangible and easy to explore without involving users.

The Trap of an Output-First Mentality

If you’re reading this article, you’ve probably attended meetings with stakeholders who want to build something new and cool and everyone is arguing about the latest thing to produce, what it should look like, and which features to include.

No one can agree because the discussion is based on unproven assumptions. It’s like going to the dentist with a toothache and having your teeth pulled out without an examination. That’s indeed one of the many things that the dentist can do, but I hope you’ll all agree that just because it can be done doesn’t make it a good idea. Any good dentist would collect evidence first before making a diagnosis or offer treatment. (X-rays are the dentist’s equivalent of our user research methods.)

Teams who carefully consider users’ intents and needs produce better products because they know what people want and are not guessing what output might be best. The world is full of examples of useless products or features that nobody uses because they didn’t fill a need.

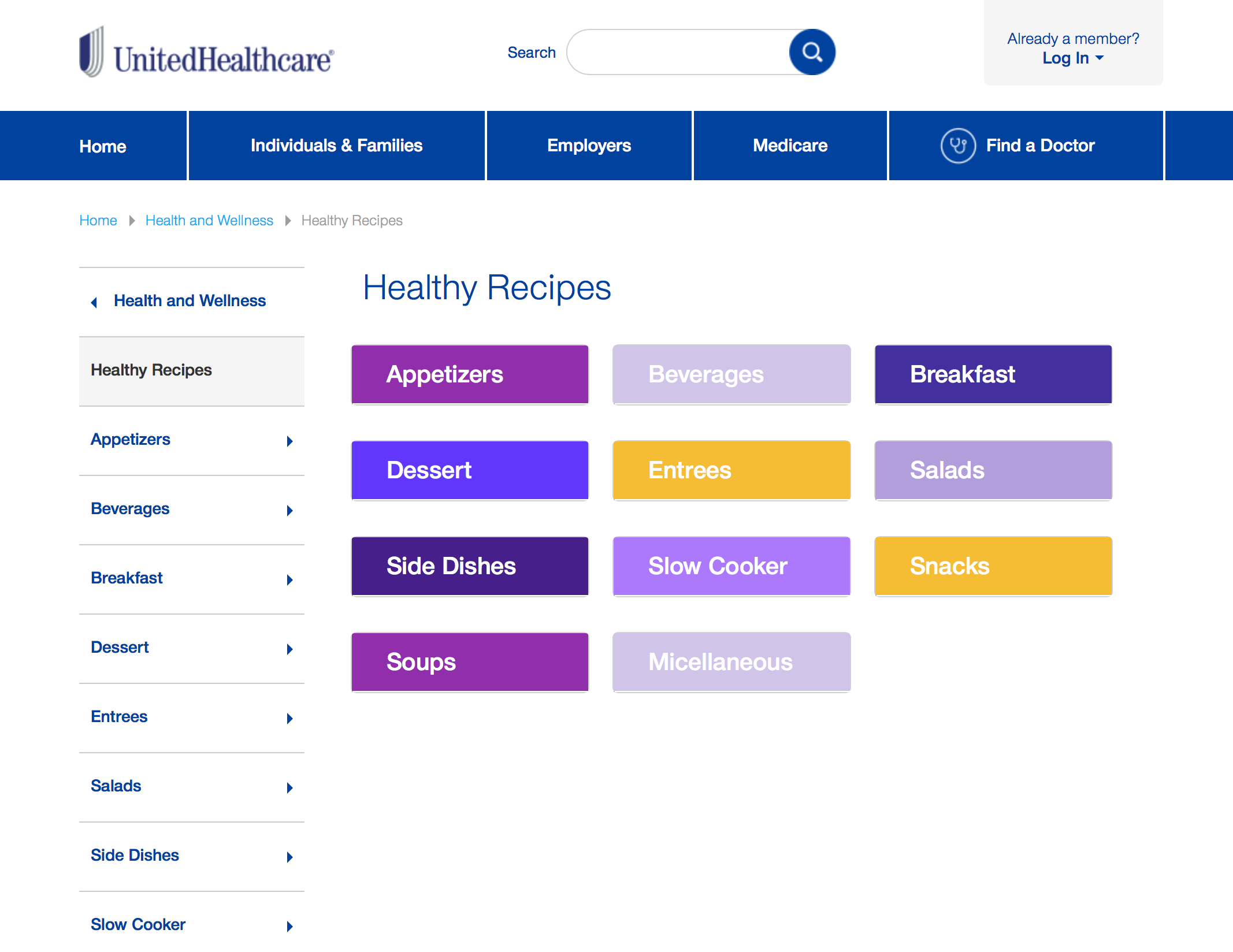

Take for example, the features offered by UnitedHealthcare, a health-insurance provider in the US. Its website offers a section for healthy recipes. While recipes are valuable on their own, most people visit health-insurance websites for information on their healthcare coverage, not for cooking tips. The Recipes section on this website is a feature completely detached from the actual users’ needs and deviates from the website’s core purpose.

UnitedHealthcare’s mobile app provides a feature called Build a Better Me. At first glance, it’s unclear what this feature does. Upon inspection, it appears to be a health-and-fitness tracker — something that most people would not expect to do here unless there are strong customer benefits. If the app shares fitness data with the insurance company or their care providers in exchange for premium discounts or personalized medical advice, it’s not apparent from the interface.

5 Steps For Ensuring Valuable Outputs

So how do you anticipate user expectations and minimize risk? Before deciding on design solutions, complete the following steps:

-

State the Problem

Work with your team to develop a shared understanding of the problem you’re trying to solve, and who they’re solving it for. Have answers to questions such as:

- Which user problems or needs are you trying to solve?

- For whom are you solving this problem?

- How does solving this problem help your business?

This first step is invaluable for framing your solution. However, in the excitement of product creation, teams often skip it and the business suffers in the long run.

Outcomes need to support both user goals and business goals. Business goals can involve metrics such as increased acquisition and conversion. User goals could range from time saved, increased convenience, to feeling delighted. Aim for solutions that serve dual purposes.

Circumvent potential disaster by steering discussions towards the problem you’re solving. Spend a little time thinking about the problem, and you’ll spend less thinking about the solution. Just because you have the technology to build something cool, it doesn’t mean you should. Relying on the notion of “build it and they will come” is hugely risky when competition is fierce and customers are protective of their time.

2. Gather User Data to Prove It

What data do you have to inform the answers for step 1? Don’t make major product decisions based on your gut because cognitive biases work against you. They can easily cause you to make costly mistakes.

You might think that your latest idea is amazing, but your customers might not. Vet a candidate solution by making sure that it addresses a real user need and not an imaginary one.

Look at existing data from field studies, competitive analysis, analytics, and customer support. Analyze the information, spot any gaps, and perform any additional research required to help you verify the answers to questions in the previous step.

3. Define Core Competencies

What is your unique skill or technology that creates value for customers? A core competency is the organization’s strategic strength. Knowing who you are and what you’re good at keeps you focused on building the right features.

Core competencies help you distinguish your products from your competitors’ and gives you a sustainable competitive advantage.

A common mistake among amateur app and website developers is to give in to the temptation to add popular or trendy features. (If something is popular, but peripheral to your mission, somebody else is probably already doing it much better than you could hope to achieve.) The most successful sites and apps are the ones that stay true to their core competencies. They purposely do few things, but they do them well.

4. Set Concrete Goals and Define Success Criteria

When team members have specific goals in front of them, the discussions become more focused and productive. And once you have a goal, define clear, operational criteria of success for it, so that you can recognize when it has been achieved.

The project’s goal should be the litmus test for deciding which output to support. Concrete goals prevent you from feature bloat or from making risky radical-redesign decisions when smaller incremental changes will do.

5. Test Multiple Ideas

Encourage team members to be creative and think of different ways to approach a goal. Generate multiple solutions and get user feedback early. Activities such as storyboarding and wireframing have two major benefits: (1) they give team members a way to communicate ideas visually; (2) teams can use the resulting artifacts to get feedback from potential customers. Based on feedback from users, identify the good and bad ideas so that you can focus on the right solution and avoid wasting resources in the design and implementation phase.

Conclusion

If you think that spending time at the beginning of projects for discovery is too frou-frou for your fast-paced projects, be warned: the alternative is bleak. Chasing the next shiny technology or visual-design trend while neglecting the needs of customers could lead you back to the days of superfluous outputs such as Flash intros and parallax scrolling.

There’s a further business advantage to an outcome-led design process: these outcomes turn directly into customer benefits that can be promoted in your marketing materials. Not only will the product be better, it’ll also be more likely to sell because you’ll know how to advertise it.

Resist the temptation to lead with the features in a UX design project. Know the customer problem before deciding how to solve it.

Share this article: