Stories are a natural part of our lives. We tell, read, and listen to stories every day — from listening to the news to recounting the events of the day. These stories are our way of remembering and communicating experiences.

The effect of stories on human memory has been well documented by many psychology experiments. Among the first one was the famous 1932 “The War of the Ghosts” experiment, in which participants read a Native American story, unfamiliar to them. That study as well as many others indicate that people’s memory is better when facts are laced together in a coherent story than when they are presented independently, in isolation from each other. And, although people tend to remember the gist of the story, they also adjust the details to match their own prior knowledge and experiences. (We further discuss the effects of stories on human memory in our class on The Human Mind and Usability.)

The same applies to stories in user experience. When used to their full potential, UX stories create a shared vocabulary, add to the organizational memory, focus the team on a common goal, ignite the audience’s imagination, and persuade stakeholders — ultimately leading to buy-in. This article discusses how to use storytelling in user experience.

What Is a UX Story?

Definition: A UX story is an account of events from the user’s perspective; the events in the story show the evolution of an experience.

A successfully crafted story should be compelling and evoke emotion, transcending culture and expertise. It can describe a current, as-is situation, or be set in the future.

UX-Story Components

The structure and components of user-experience stories are not far removed from fairy tales, classical theater, or box-office films. According to Aristotle, successful drama is composed of six primary elements: plot, character, thought, diction, music, and spectacle. These elements remain essential to modern day’s storytelling and create the infrastructure for the components mentioned below. (While music is optional in most corporate environments, we recommend a bit of spectacle for your story presentation, maybe in the form of a prop or two.)

A UX story has the following components:

- User. Compelling stories must have a clear, fleshed-out main character (or, in some cases, multiple characters), with whom the audience can empathize. Imagine a main character who is hard of hearing. Framing your story from this perspective allows your audience to relate to your user— for example, by considering a parallel visual experience for aspects that would have been only audible.

- User’s goal and motivation. The goal establishes a clear understanding of the task at hand, while the user’s motivation helps the audience see the meaning behind the user’s behaviors and decision making. For instance, in a UX story about a teenager, her goal (e.g., downloading a new app), is just as valuable as her motivation, which could be social acceptance or making friends.

- Context. Context is the setting (time and place) in which the UX story takes place. Providing an environment for the story aids in understanding where the designed experience fits in. This context can also act as the starting point from which the plot can be built — it can be the source of story conflict or obstacles that the character must face before achieving his goal. The right context gives your audience something concrete to buy into. For example, imagine a busy father. If this character is surrounded with context such as a barking dog, full hands, and a sick baby, the team can understand the environment that it must design for: chaos, high stress, and little time.

- Plot. A plot describes a series of events along a timeline. Often, these events build tension and crisis as the main character (the user) heads towards the climax in the story.

- Insight. While the previous four components are straightforward, insight is where storytellers must insert their understanding and communicate to the audience the significance of the situation. Insight can become emotionally engaging when the audience senses that something is at stake or that the main character’s core values are disrupted. Insight is often the “aha moment” of the story — the pain point that the team didn’t know existed, but has been uncovered through research, or the design breakthrough that is going to change the user’s future experience.

- Spectacle. Spectacle refers to the visual portion of the story. This could be props, drawn illustrations, or video. The spectacle usually makes the story more memorable and enjoyable, and keeps the audience interested and involved.

What Makes a Good UX Story

The user and her goals are the most rudimentary components of a story, upon which empathy, context, conflict, plot, and insight can be built. A good UX story should be simple, yet engaging enough and accessible to a range of audiences: young to old, beginner to expert. Tell your story to a 16-year-old, then a 60-year-old; do they both understand the characters and plot? Do they both stay engaged throughout? If not, work to make your story more attainable and compelling.

A successful story can benefit the design and development cycle in several ways:

- Keeping the user at the center of the conversation. Make sure the point of view and focus never shift from the user.

- Discussing topics you may not be able to address in direct ways. Stories let you bring up controversial topics in a neutral way.

- Concretizing abstract design notions. By tying these elements into a story, you create a context that allows for a shared understanding of otherwise hard-to-grasp concepts.

- Facilitating comprehension and memory. As discussed in the beginning of the article, stories improve the ability to recall information.

- Setting the stage for persuasion and a call to action. When an audience is invested in the story, characters and plot will be more persuasive and more likely to generate buy-in.

UX Stories vs. Scenarios, Use Cases, or Storyboards

It is likely that you are already using multiple types of storytelling in your work — use cases, scenarios, storyboards — to illustrate particular aspects of the user experience. Though these are all valid and valuable, they differ from the type of UX story suggested in this article.

Use cases, scenarios, and storyboards focus on developing the correct sequence of actions to capture an activity, usually in order to outline requirements. Their primary purpose is to describe. More often, these focus on the technology, not on the user. Use cases, scenarios, and storyboards often lack character development, plot, and user goals — though their scope and granularity can vary.

In contrast, UX stories are specific; they have developed characters, context, and well-formed plots. The audience leaves with a clear understanding of the user’s goals and motivations. While other methods of storytelling are valuable, these stories — ones that communicate the value of the experience to its users — will be the focus of this article. Specificity means memorability (which is also why personas are more memorable than abstractions such as audience segmentation profiles).

Using UX Stories Throughout the Design Process

Stories can be written, drawn, spoken, or recorded. They are a powerful tool throughout multiple stages of the design process and can serve accomplish each of the following goals:

- Summarizing user research. Qualitative user research is made of stories. These stories naturally exist in observations, survey data, interviews, customer-service transcripts, research notes, and/or conversations. The goal is to harness these fragments and build on them until you have a compelling narrative that accurately captures the insights gathered from your research. Stories crafted to summarize user research should:

- Illustrate the user’s pain points.

- Reflect the current experiences of your real users, and not ideal experiences that you may want for them (in other words, the point of view should be “as-is” instead of “to-be”).

- Bridge multiple sources of data.

- Avoid prescribing a design solution.

- Generating ideas. After you’ve collected stories from research, you can use them to prompt innovation. Take the existing stories and begin to alter them to uncover ways to enhance the user’s experience. The primary purpose of stories in this context is to be generative; thus, deferring judgement and embracing wild ideas is key. Start by taking your as-is story (from user research) and asking yourself “what-if.” Brainstorm as a group by storytelling in a circle, each person adding to the story as it progresses.

- Conveying abstract concepts. Experiences are naturally hard to communicate, especially when they are still at idea-only stage. UX stories are a powerful way to articulate abstract concepts by focusing on the user value that will be derived from the experience. Rather describing the finite details of how a user may move through an app tap by tap, tell a story about what the user was doing before the app existed, the pain she experienced, and how the app alleviated that pain. A story that shows how a new offering will be used is more cohesive, comprehensive, and meaningful than a to-do list of functional requirements or proposed features. When conveying abstract concepts through a UX story, aim to:

- Keep the story high level so that the feedback is concept related (rather than visuals or interface related)

- Craft a compelling beginning-to-end story.

- Focus on the experience as a whole, not on unfamiliar technology.

- Persuading the audience. A critical success factor for UX work is how much confidence it gains from stakeholders — from developers, to product managers, to executives. UX stories help tremendously when aiming to persuade because they transcend expertise and bias. They enable everyone to understand and agree on common goal; they help the audience empathize with the user. The story can also become a tangible artifact that can be distributed or referred to as needed.

- Evaluating designs. Stories can serve as a baseline for measuring success. Try re-telling the story from the same user’s perspective, but using your updated design. Have the pain points been removed? Have new pain points arisen?

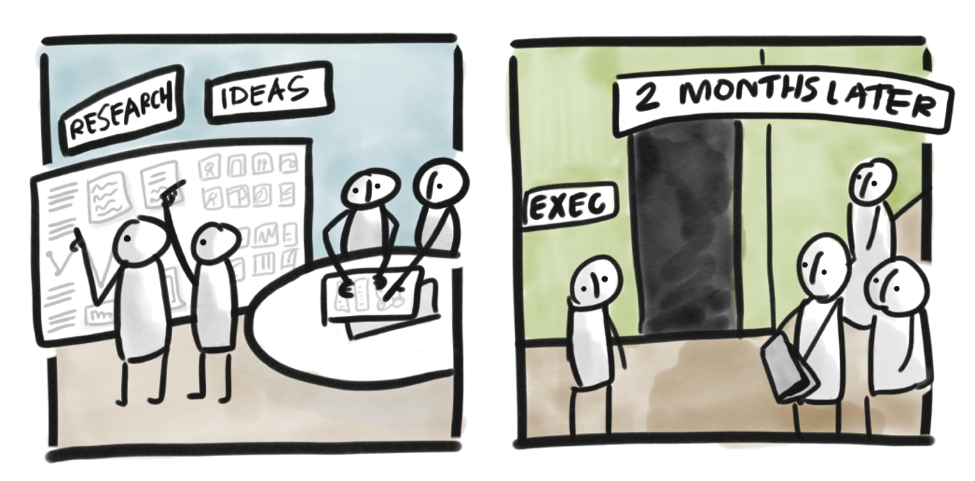

A team is given a problem to solve. It gathers user data to drive a user-centered, innovative idea. After working hard on a viable, vetted solution, the team members prepare to present it to executives.

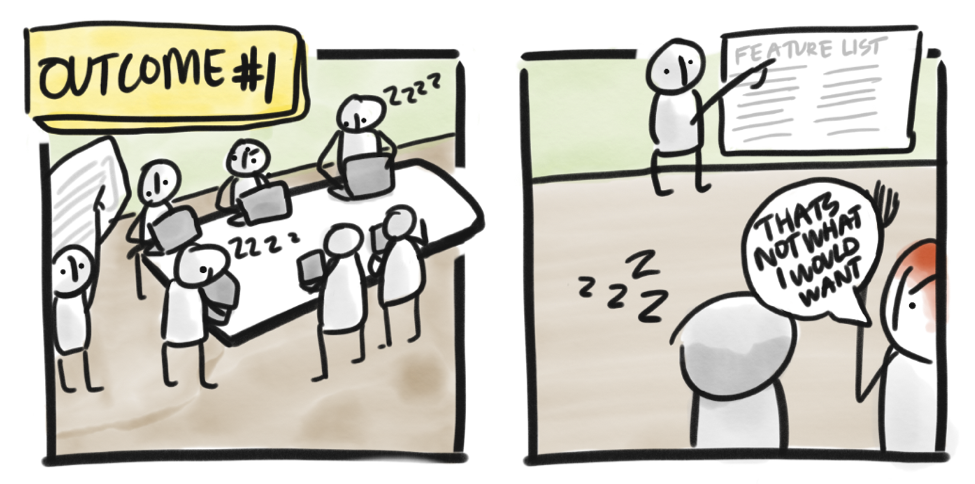

The team walks through each screen, describing features and capabilities. When it comes time for discussion, some stakeholders are asleep while others become disgruntled in disagreement.

Rather than showing the design screen by screen, the team decides to present it in a different way. The team tells an empathetic story about Alice — who she is and what motivates her. The executives are placed in the context of her day: stuck in rain and running late.

“Thoughts start racing through Alice’s head. How late is the bus going to be? Is she going to be fired? Will she have to stay late and miss school pickup? But maybe this isn’t the way it has to be for Alice...” Through the engaging, compelling story, the execs are able to arrive at the same understanding and conclusion as the team.

Risks of UX Stories

Your stories must stay rooted in UX data; otherwise, you may believe in your stories more than in your users and end up with products that satisfy imaginary needs. To avoid this danger, check in regularly with your end users as your story evolves over time and make sure that you staying grounded in real pain points and needs.

Conclusion

UX stories are a communication tool that can be used in lieu of boring task check lists that are far removed from the user. They provide a natural, engaging way to share behavior, perspectives, and attitudes.

User-experience stories are ultimately about knowing your audience and how to engage it. Be sure to consider the audience’s awareness about the story’s context. Finding a way to end the story in a settled, memorable way can facilitate conversation around the topic of your choice.

In many business contexts, storytelling feels foreign and uncomfortable, but stories can spark the imagination of those hearing them. This rich way of communicating can help set the stage for persuasion or a call to action, ultimately bettering the design at hand.

Learn more about storytelling in our full-day training course on Communicating Design.

Reference

Quesenbery, W., & Brooks, K. 2010. Storytelling for User Experience: Crafting Stories for Better Design. Rosenfeld Media, LLC.

Share this article: